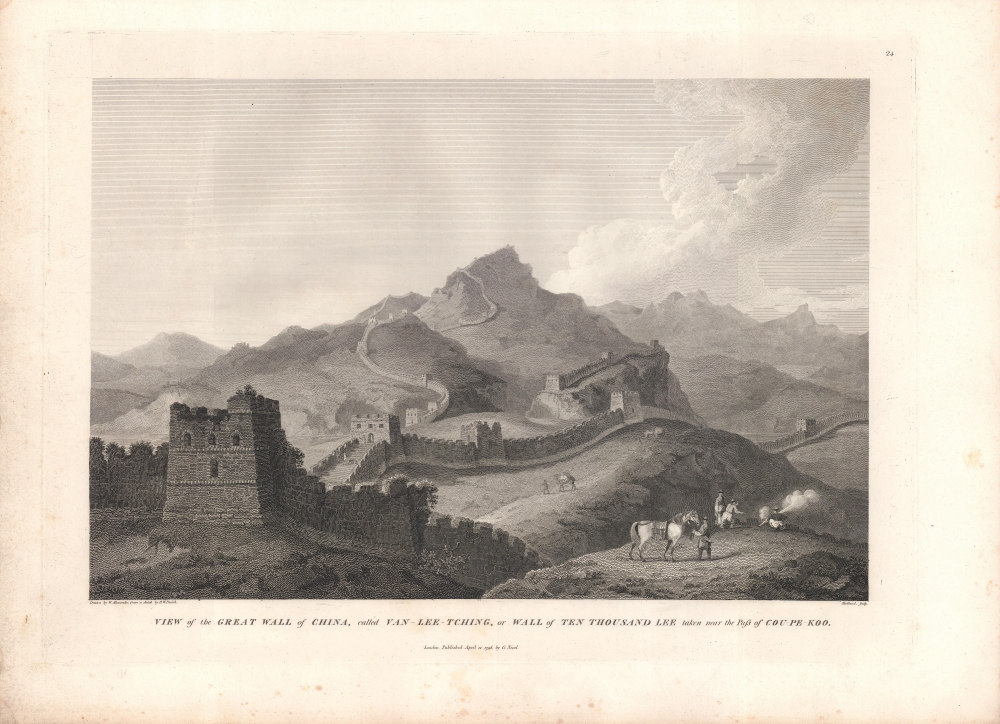

1796 Alexander View of the Great Wall of China at Gubeikou

GreatWall-alexander-1796

Title

1796 (dated) 22 x 15.25 in (55.88 x 38.735 cm)

Description

A Closer Look

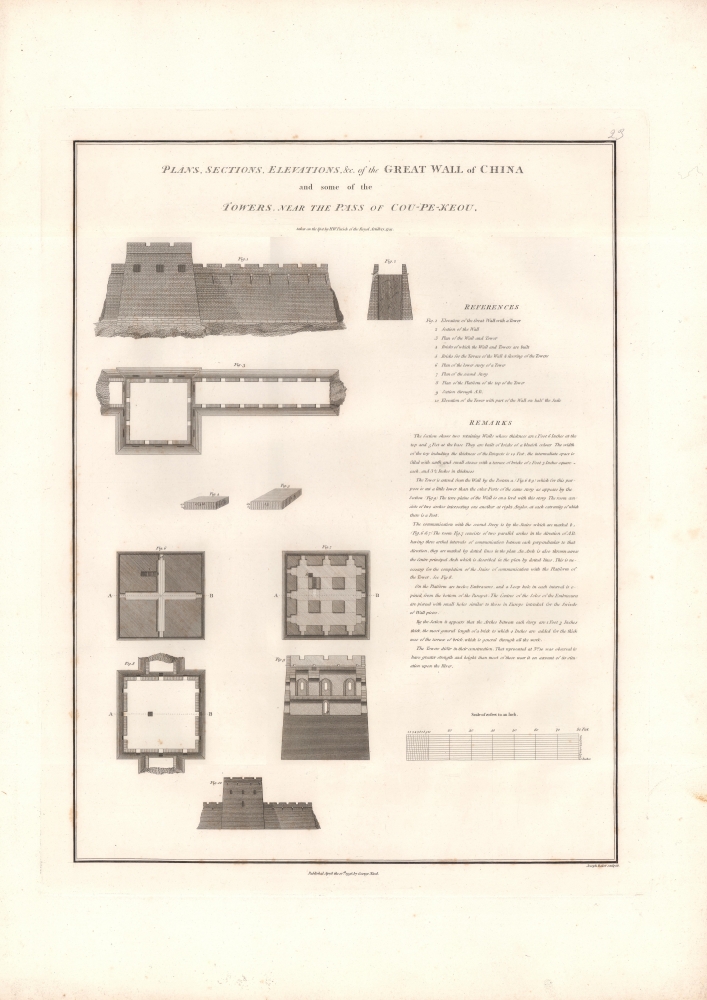

The title refers to a traditional name of the wall, wanli cheng (萬里城 or 萬里長城), and to the important gate through the wall as Gubeikou (古北口, roughly 'old north entrance,' which is not itself depicted). The wall moves along a chain of hills in the background, while traders, soldiers, and members of Macartney's Embassy are depicted in the foreground. The verso (engraved by Joseph Baker) includes a detailed schematic including cross-section drawings of different portions of the wall with explanatory remarks.When Macartney's group arrived in Beijing in late August 1793, the Qianlong Emperor was undertaking a hunting expedition north of the Great Wall. Thus, the embassy proceeded to the Qing summer palace at Chengde (Rehe), also north of the Great Wall, where the Qing emperors often received delegations from vassal states. In doing so, they had to pass through the Great Wall at Gubeikou, at which point Macartney tasked Parish with surveying the Great Wall's fortifications (the surveying work seemingly depicted here at left), which caused the Qing troops and officials escorting them to become suspicious.

However, this intelligence work was somewhat beside the point, as the wall had greatly decreased in importance during the Qing era. As Manchus hailing from beyond the Great Wall, once they had passed through it (at Shanhaiguan) en route to conquering Beijing in 1644, the Qing did not imbue the wall with the cultural or military significance that their predecessors, the Ming, had. One can see here how the fortifications had already begun to degrade by the time Macartney's Embassy arrived.

Nevertheless, the wall gained currency in the Western imagination as the embodiment of Chinese culture and Parish's sketch was widely imitated, creating a small genre of wall views popular in the late 19th century. In the 20th century, Chinese nationalists and intellectuals also resurrected (or more accurately invented) the importance of the wall as a cultural symbol, both a historical dividing line between Chinese civilization and nomadic 'barbarians' and a representation of the Chinese nation itself, ancient and solid. The wall being the site of battles between Chinese troops and Japanese invaders in the mid-1930s added to its significance in this regard, and it was commemorated in the patriotic song 'Great Wall Ballad' (長城謠), still popular today. Gubeikou is not among the most popular tourist sites along the wall near Beijing, and the wall there is in significantly worse condition than Parish found it, though still easily recognizable.

The Great Wall of China

Perhaps the single most prominent symbol of Chinese culture and history, the Great Wall may also be the most misunderstood. Rather than a single wall, it is a system of fortifications ranging over hundreds of miles and differing in height, depth, and age. Frontier fortifications along the edge of the nomadic steppe predate the era of unified imperial rule but were first systematized and unified by the briefly-lived Qin Dynasty (221-206 BCE). Later dynasties renovated and elaborated these fortifications as circumstances dictated, though for much of imperial history the Qin era walls were left to slowly degrade.The impressive walls that exist today in the vicinity of Beijing were built in the early Ming Dynasty, the result of a decades-long battle with Mongol nomads, including the remnants of the preceding Yuan Dynasty. Some dynasties, particularly those that had originated beyond the wall, like the Yuan and the Qing, paid little attention to these fortifications. In fact, the close association of the wall with Chinese civilization is a relatively recent phenomenon, derived in part from Western travelers (especially missionaries) who first arrived in China during the Ming era, and in part from Chinese in the early 20th century who sought a powerful symbol of national identity to unite the disaggregated and beleaguered country.

The fortifications are generally seen as having been intended to prevent raids from nomads on sedentary communities, but a simple picture of nomadic-sedentary conflict obscures a much more complicated reality, in which the two communities traded and intermarried as much as they fought or stole from each other. Individuals, clans, and entire communities sedentarized by migrating south of the wall and integrating with existing inhabitants, and some then become nomadic again. Some sedentary communities 'nomadized,' leaving their farms to take up pastoralism. Some set up farms well beyond the Great Wall, especially in the late imperial era when land was scarce. Historians believe that the walls may have been intended to keep people in as much as keep nomads out. Onerous taxes, corvée labor requirements, and military conscription drove refugees to flee the tyrannical Qin state and the nomadic frontier provided a neat way to do so. Even later dynasties, which generally were less oppressive, found it inconvenient that people could skirt tax obligations or evade the law by escaping to the frontier and thus had an incentive for regulating movement between the sedentary and nomadic realms.

The Macartney Mission

The Macartney Embassy was a diplomatic mission by Great Britain to the Qianlong Emperor of the Qing Dynasty meant to expand British trading rights in China and establish a permanent embassy in Beijing. Thirty-five years earlier, British traders of the East India Company (EIC) were confined to trading with an officially sanctioned set of Chinese traders in Canton (Guangzhou). Although the Canton System was profitable, the EIC found it too cumbersome and restrictive, while also feeling that a direct line to Beijing was necessary to resolve disputes, rather than working through several layers of intermediaries and bureaucrats. A mission led by Charles Cathcart had been sent to Beijing in 1787, but Cathcart died before reaching China and the embassy was abandoned.George Macartney's mission left Britain in September 1792 with a retinue of translators, painters, secretaries, scholars, and scientists. The embassy traveled via Madeira, Tenerife, Rio de Janeiro, the Cape of Good Hope, Indonesia, and Macau, before moving up the Chinese coast and reaching Beijing on August 21, 1793. Macartney's second in command was George Leonard Staunton who served as the expedition's secretary and chronicler. Staunton's eleven-year-old son, George Thomas Staunton, nominally the ambassador's page, learned Chinese during the voyage, became very adept at the language, and served as a translator for the mission alongside the Catholic priests Paolo Zhou (周保羅) and Jacobus Li Zibiao (李自標). The younger Staunton later became chief of the East India Company's factory at Canton, translated works between Chinese and English, and helped found the Royal Asiatic Society.

The embassy was poorly managed from the beginning and, despite considerable pomp from the English perspective, appeared poor and rag-tag to the Qianlong Emperor. Partly through lack of preparation, partly through arrogance, and partly due to the emperor's distaste for the British, the embassy failed in all its primary objectives. This disappointing result was compounded by a now famous letter from Qianlong to King George III that chided the British monarch for his audacity in making demands of the Qing and his ignorance of the Chinese system, ending with a reminder not to treat Chinese laws and regulations lightly, punctuated with the memorable phrase 'Tremblingly obey and show no negligence!' (a common phrase used by the emperor in communications to his own subjects).

Macartney's Mission highlighted cultural misunderstandings between China and the West, and has often been taken as a turning point in Chinese history. Qianlong's dismissal of foreign objects as mere toys and his insistence of the centrality of China in the world's hierarchy of kingdoms have been seen as sign of Chinese intransigence and a harbinger of China's awful course in the 19th century. At the time the embassy visited, Qianlong had been in power for nearly sixty years and had increasingly turned over management of the empire to a small group of self-serving officials, particularly Heshen, remembered as the most corrupt official in Chinese history. In the countryside, overpopulation and famine provoked millenarian religious movements and uprisings. On the southern coast, the EIC began importing opium in larger and larger quantities, eventually causing a severe social and economic crisis throughout southern China. In retrospect, both Chinese and foreign historians of every ideological bent have seen the Macartney Mission as a missed opportunity for the Qing to recognize the tremendous changes taking place in Europe and address the underlying problems that would eventually sink the empire.

Publication History and Census

This view was drawn by William Alexander based on a drawing by Henry William Parish and was engraved by Thomas Medland for inclusion in the first edition of George Leonard Staunton's An Authentic Account of an Embassy from the King of Great Britain to the Emperor of China, published in London by George Nicol in 1797. It is only independently cataloged in the holdings of the Victoria and Albert Museum, while the full Authentic Account is well-represented in institutional collections.CartographerS

William Alexander (April 10, 1767 –July 23, 1816) was an English painter, illustrator, and engraver. He was one of the appointed draughtsmen on Lord Macartney's famous embassy to China, and several of his drawings were published in George Leonard Staunton's An Authentic Account of an Embassy from the King of Great Britain to the Emperor of China in 1797. Alexander was an accomplished artist from a young age, moving to London at 15 to study with William Pars and Julius Caesar Ibbetson. At age 16, he was admitted to the Royal Academy Schools, and he soon gained the support of the acclaimed artist Sir Joshua Reynolds. Following the Macartney embassy, he continued to publish works related to voyages to Asia and the western coast of America, including Vancouver's famed expedition. In 1802, he was appointed professor of drawing at the Military College at Great Marlow, and then took a position as assistant keeper of antiquities at the British Museum, where he undertook a project illustrating the museum's collection of terra cottas and marbles, which remained uncompleted at the time of his death. More by this mapmaker...

Henry William Parish (fl. c. 1792 - 1797) was a British artillery officer best known as a draughtsman and head of the artillery detachment on Lord Macartney's embassy to China. Several of his drawings were published in George Leonard Staunton's An Authentic Account of an Embassy from the King of Great Britain to the Emperor of China in 1797. Parish also surveyed portions of the Great Wall of China as the embassy moved towards Chengde, the summer residence of the Qing emperors. Learn More...

Thomas Medland (c. 1765 - 1833) was a British artist and engraver. He served as the drawing-master at Haileybury College, a school founded by the East India Company, and acted as landscape engraver to the Prince of Wales, the future King George IV. A master of the aquatint etching technique, his works were regularly displayed at the Royal Academy and he produced impressive plates for several successful publications, including George Leonard Staunton's An Authentic Account of an Embassy from the King of Great Britain to the Emperor of China and William Gell's The Topography of Troy, and its Vicinity. Learn More...

Joseph Baker (1767 - 1817) was a British naval officer and explorer best known for his service under George Vancouver during the historical Vancouver expedition to map the Pacific Northwest. Vancouver was born in the Welsh border counties. He joined the Royal Navy in 1787 where he met and befriended then-Lieutenant George Vancouver and then-Midshipman Peter Puget. When Vancouver was commissioned to complete the exploration of the American Northwest Coast, he chose Baker as he 3rd Lieutenant and Puget as his 2nd Lieutenant. During the course of the expedition Baker was assigned the task of converting surveys into working maps and his name appears on many of Vancouver's most important maps, including the first complete map of the Hawaiian Islands. Baker, along with the expedition's naturalist Archibald Menzies, completed the first recorded ascent of Hawaii's Mauna Loa volcano. Mt. Baker, in modern day Washington, is also named after him. In his journals Vancouver wrote admiringly of Baker's work:…my third Lieutenant Mr. Baker had undertaken to copy and embellish, and who, in point of accuracy, neatness, and such dispatch as circumstances admitted, certainly excelled in a very high degree.

Following the Vancouver expedition Baker briefly retired from naval service until being recalled and made Captain in 1808. Assigned to the ship HMS Tartar, Baker was charged with escort duty in the Baltic. There, in a series of skirmishes with Danish privateers, Baker fell afoul of his British superiors and was court-martialed. Although acquitted of the court martial, Baker never again served in the Royal Navy. He retired to Presteigne where he maintained a long standing friendship to Puget, who moved to the same town on his own retirement. Learn More...