This item has been sold, but you can get on the Waitlist to be notified if another example becomes available, or purchase a digital scan.

1929 J. P. Wong Map of San Francisco Chinatown, California

SanFranciscoChinatown-wong-1929

Title

1929 (undeated) 18.5 x 26.5 in (46.99 x 67.31 cm) 1 : 1200

Description

The Map

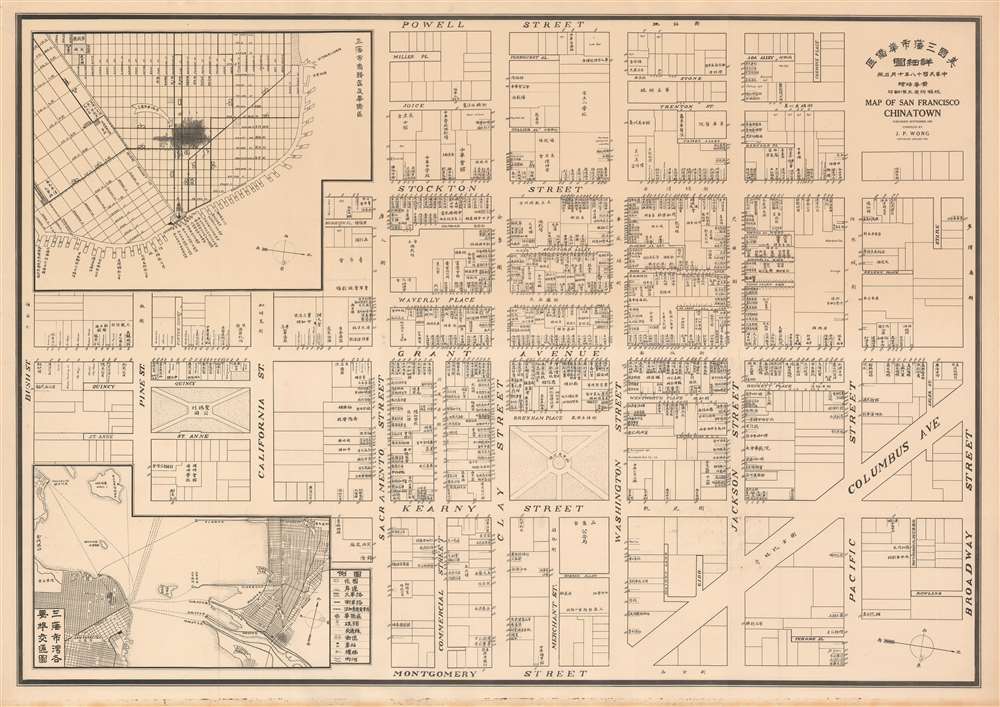

The map is oriented to the west and covers Chinatown from Bush Street to Broadway Street and from Powell to Montgomery. Insets in the upper left and lower right illustrate San Francisco Chinatown's position in relation to the broader metropolitan and Bay Area. Chinese owned and operated businesses and buildings are individually identified in Chinese, with very few non-Chinese businesses noted, and those of which are noted, in English, appear to be Japanese-owned. The level to which non-Chinese businesses are fully ignored underscores the fact that they were not considered important and that is map is exclusively by and for Chinese-Americans.San Francisco Chinatown

Covering roughly 24 blocks, San Francisco's Chinatown is the oldest Chinatown in the North America and the densest chines enclave outside of Asia. It was established in 1848, but did not grow significantly until the influx of Chinese immigrants following the California Gold Rush between 1849 and 1955. The area was official designated as the only part of San Francisco that allowed Chinese persons to own, inherit, and inhabit property. It quickly developed a reputation as a den of vice, with countless houses of prostitution and gambling. Nonetheless, despite, or perhaps because of this reputation, it became a popular tourist destination for those seeking the 'mystery of the orient.' During the San Francisco Earthquake and fires of 1906, Chinatown was particularly hard hit due to the density of wooden structures and completely destroyed. Although some city officials saw this as an opportunity to move Chinatown out of downtown San Francisco - this did not happen. Instead the Chinese quickly rebuilt, hiring architects to construct Chinese-inspired buildings in the hopes of attracting tourists. Unfortunately lack of adequate housing led to a period of decline for San Francisco's Chinatown until immigration reform in the 1960s precipitated a second enormous wave of Chinese immigration. The area went through a revival, attracting tourists once again, but retained its reputation as a hub of vice and seedy nightlife. Today Chinatown celebrates its Chinese heritage and remains a center of Chinese culture in San Francisco.Chinese Six Companies

While not explicitly noted, the map was issued at the direction of the Consolidated Chinese Benevolent Association, also known as the 'Chinese Six Companies.' This was a pro-Chinese advocacy group established in 1882, initially to assist Chinese people to travel to and from the United States, but later as a community management board in opposition to the criminal Tongs. The board had connections to local and federal governments and used its influence to protect Chinese immigrants from racist anti-Chinese policies prevalent in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. It has been reported that, at the time, an example of this map hung in the Benevolent Association's offices where pins were placed over businesses that were in arrears of their dues.The Tongs and This Map

Despite being prepared for the Chinese Six Companies, it is believed that this map was almost immediately co-opted by the criminal Tongs to collect extortion money from Chinese-owned businesses. The Tongs were mafia-like secret societies that had long been a bane to the San Francisco Chinese community. Throughout the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the Tongs ran San Francisco's Chinatown in parallel to the Six Companies, but had a far more violent extortionist approach - a situation that led to a complex network of rivalries, alliances, and battles between the two groups.As this map went to press, the San Francisco Police department, led by John J. (Jack) Manion, was in an all-out war with the Tongs. Kind of like a Bay-area Elliot Ness, Manion led his 16-member squad on countless raids throughout Chinatown, shutting down Tong-related enterprises and arresting suspected members. The map's author, J. P. Wong, was twice arrested in Manion's raids, once for bootlegging and another time for gambling. It is not inconceivable that it these arrests, as much as his political ideologies, may have contributed to Wong's 1929 decision to return to China.

Publication History and Census

This map was prepared by J. P. Wong (黃華培, Huang Huapei) and published on behalf of the Consolidated Chinese Benevolent Association. The copyright registration dates it to September of 1929. This map is rare. We have identified four known examples, at least one of which is little more than a digital reference.Cartographer

J. P. Wong (黃華培, November 18, 1901 - December 6, 1988), also known as Huang Huapei, was a Kuomintang (KMT) nationalist active in San Francisco throughout the 20th century. Wong was born in Daxiuyong, China and emigrated with his family to San Francisco in 1913. He joined the Kuomintang party in 1922 and became an officer of the San Francisco branch of that party. There is some suggestion that, at this time, he may have worked as a Chinese-language newspaper reporter. By 1926 he was actively raising funds and recruiting from the Chinese-American community in San Francisco for the National Revolutionary Army and the Northern Expedition. In the same year, he was involved with a Chinatown bootlegging ring and arrested. Wong published one map, a detailed mapping of San Francisco's Chinatown for the Consolidated Chinese Benevolent Association, with which he was associated. Later that year, 1929, Wong returned to China to support the KMT, becoming prominent in Shanghai where he moved in elite political circles. Wong returned to the United States only after 1949 when the mainland KMT nationalist regime collapsed. In 1951 he acquired an ownership share in the Hang Ah Tea Room (香雅. The oldest standing dim sum house in America), which is still active, using it as a platform to support the KMT in San Francisco. Wong became a citizen of the United States five years later in 1956. He was on the board of directors of Young China and in 1974 was an adviser to the Taiwan Overseas Chinese Affairs Commission (OCAC). He did not return to mainland china gain until 1980 and in 1981 was invited to the 70th anniversary commemoration of the 1911 Revolution. Wong died in San Francisco in 1988, aged 87. More by this mapmaker...