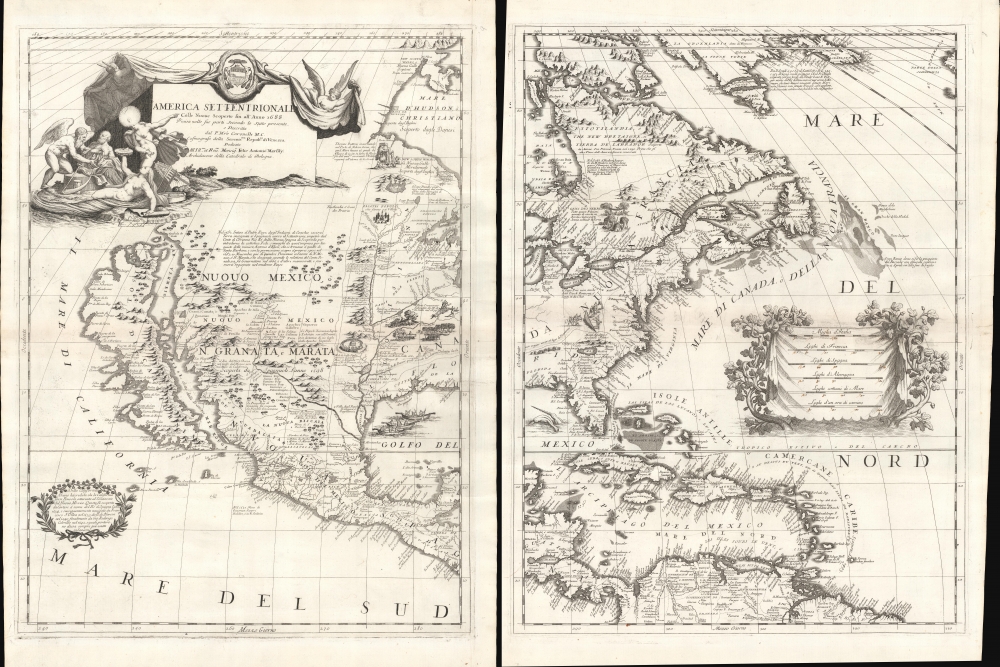

1688 Coronelli Map of North America (2 Sheets)

AmericaSettentrionale-coronelli-1688

Title

1688 (dated) 26.25 x 39.25 in (66.675 x 99.695 cm) 1 : 11800000

Description

A Closer Look

On two uncolored folio sheets, as issued, this map embraces North America from the Atlantic to the Pacific and from Hudson Bay to Panama, thus including all of Central America and the West Indies. The cartography, vignettes, and other detail mirrors Coronelli's 1688 globe gores, but, as Burden notes, neither the gores nor this map has clear primacy.The map is rich with detailed illustrations, placenames, factual and speculative cartography, and decorative elements. It features one of the earliest uses of the term Chicago, here 'Chekagou,' referring to the Chicago River. The Mississippi is placed well west of the Great Lakes, bordered on the west by a mythical supposed mountain range. It erroneously empties into the Gulf of Mexico in what is today southern Texas, near the Rio Grande. La Salle's forts, established in the 1660s, are noted on the Great Lakes and the Mississippi. California is boldly illustrated in an insular form on the Luke Foxe / Sanson model. The map names the supposed wealthy American Indian cities of Quivira and Teguayo (Teguaio) hidden in the mountains north of Santa Fe.

Throughout, the map is rich with vignettes and annotations featuring Indigenous Americans. These include a disturbing scene just southwest of Hudson Bay where a human leg is being smoked. Other images include fish preparations, villages, an alligator eating men, men eating an alligator, fishermen on rowboats in the Gulf of Mexico, and more.

The confounding yet striking Venetian Baroque cartouche in the upper left features several divine or angelic figures. A ship appears wrecked beneath them, the long tresses of another flow beneath like water, and still a third features a heavenly halo. They are surrounded by scientific and navigational equipment. Just to the right, the map bears a dedication to Felic Antonio Marsily, Archdeacon of the Cathedral of Bologna.

La Salle, Peñalosa, Coronelli - Ambition and Treachery

This map is the first to capture one of the most compelling narratives of exploration, ambition, and treachery in the history of North American colonization. Coronelli's map draws heavily on the explorations and imagination of an elusive but noteworthy figure, Diego Dionisio de Peñalosa Briceño y Berdugo (1621 - 1687). Peñalosa was a Peruvian-born Creole descended from Spanish nobility. Through an array of misadventures, he briefly became Governor of New Spain before falling afoul of the Inquisition, resulting in his exile. He concocted a plan for self-aggrandizement and revenge against Spain, which he presented to King Louis XIV of France in 1687. The King declined. Nonetheless, while in the French court, he became close with René-Robert Cavelier de La Salle, who adopted his plan and successfully presented it to the King, arguing for a French settlement at the mouth of the Mississippi. Although Peñalosa was rejected, La Salle met with royal approval, and a colonization attempt ensued.Peñalosa argued that a French colony could be easily established at or near the mouth of the Rio Bravo (Rio Grande). He suggested that the region was poorly defended and sparsely populated but that such a colony would have ready access to both the coveted silver mines of Santa Barbara and the supposed golden indigenous cities of 'Quivira' and 'Gran Teguayo.' He composed a map to this effect, which likely does not survive but was presented to La Salle and the mapmaker Vincenzo Coronelli. (There is a manuscript map attributed to Peñalosa located in New Mexico at the Fray Angélico Chávez History Library. We have not, at this time, been able to access the map for further study.)

La Salle set sail for the new world with several ships and a large colonizing party. Conventional scholarship suggests that through shipboard infighting and leadership squabbles, La Salle 'missed' the mouth of the Mississippi, instead landing several hundred miles to the west, deep in Spanish territory, not far from the Rio Bravo (Rio Grande). It is more likely that the landing was intentional, as the location followed the Peñalosa plan. Whether the King was aware of La Salle's intent to follow Peñalosa's suggestions is unclear; he may have ordered La Salle's true objectives be kept secret to avoid alarming the Spanish, or it may have been subterfuge on the part of La Salle and Peñalosa.

Either way, La Salle's colony was established near the Rio Grande on the Peñalosa model. Back in France, Coronelli, with royal patronage, composed this map based on Peñalosa's information. Peñalosa's data includes numerous previously unrecorded place names, among them settlements, forts, roads, and other important features, and the location of the Mines of Santa Barbara. Peñalosa was the first to divide the Rio Grande into the southern Rio Bravo and the northern Rio Norte and among the first to have it correctly flowing into the Gulf of Mexico. In any case, though, as Burden suggests, Coronelli may have been aware that the mouth of the Mississippi was nowhere near the Rio Bravo. However, there was a king to keep happy. By distorting the relative positions of the Great Lakes and the Gulf of Mexico, Coronelli was able to anchor the mouth of the Mississippi deep in Spanish territory, thereby dramatically expanding French claims to 'Louisiana'.

This mapping of the Mississippi had a lasting influence on cartography and history. Although the positioning of Mississippi was corrected by the end of the century, and New Orleans was founded in 1718, the positioning of La Salle's initial colony was regurgitated multiple times in the subsequent centuries, including influencing the 19th-century borders of the Republic of Texas.

Insular California

The idea of an insular California first appeared as a work of fiction in Garci Rodriguez de Montalvo's c. 1510 romance Las Sergas de Esplandian, where he writesKnow, that on the right hand of the Indies there is an island called California very close to the side of the Terrestrial Paradise; and it is peopled by black women, without any man among them, for they live in the manner of Amazons.Baja California was subsequently discovered in 1533 by Fortun Ximenez, who had been sent to the area by Hernan Cortez. When Cortez himself traveled to Baja, he must have had Montalvo's novel in mind, for he immediately claimed the 'Island of California' for the Spanish King. By the late 16th and early 17th century, ample evidence had been amassed, through explorations of the region by Francisco de Ulloa, Hernando de Alarcon, and others, that California was, in fact, a peninsula. Nonetheless, by this time, other factors were in play. Francis Drake had sailed north and claimed Nova Albion, modern-day Washington or Vancouver, for England. The Spanish thus needed to promote Cortez's claim on the 'Island of California' to preempt English claims on the western coast of North America.

California's insularity is likely based on textual records associated with the Sebastian Vizcaino 1602 expedition along the west coast of North America. In his records, Fray Antonio de la Ascension, a Carmelite friar who accompanied the voyage, described California as an island. Why he did so is unclear, but his information was published at least twice, first in Juan Torquemada's 1613 Monarquia Indiana and later in Ascension's own 1620 Relacion.

Insular California here follows the 1635 Second Sanson model based upon the supposed 1631-32 discoveries of Luke Foxe. Foxe never got close to California, but the map accompanying his 1635 narrative introduced new cartography, particularly a modification of the northern part of Insular California that included several new bays identified as Tolaago (Talaago) and R. de Estiete, as well as a curious peninsula from the mainland identified as Agubela de Cato. Foxe provides no basis for the new cartography. Still, it was embraced by Sanson in 1656 and had a lasting impact on subsequent mappings of Insular California, including that of Hendrick Doncker, Herman Moll, and, as here, Coronelli.

Nuevo Suecia [New Sweden]

The map includes but does not name the short-lived colony of Nuevo Suecia or New Sweden, wedged between Virginia and New York. Nuevo Suecia existed in modern-day New Jersey from 1638 to 1655, after which it was incorporated into the Dutch colony of New Netherland. New Netherland became British in 1664 and was renamed, as here, Nuovo Irock (New York). Though defunct, many of the original Swedish settlers remained and, although technically under English rule, retained relative autonomy. The borders of New Sweden had a lasting influence on cartography, as they later resolved into East and West Jersey.Danes in Hudson Bay - Jens Munk

Jens Munk, a Danish explorer, led an expedition to Hudson Bay in 1619-1620 in an attempt to discover the Northwest Passage to Asia. Sponsored by King Christian IV of Denmark-Norway, Munk set sail with 64 men on two ships, the Unicorn and the Lamprey. After navigating the treacherous waters of the North Atlantic, the expedition reached Hudson Bay in late 1619. They explored its shores, claiming it for Denmark and hoping to find a passage westward, but were ultimately forced to winter near the mouth of the Churchill River due to ice. The harsh Arctic winter proved devastating, with cold, starvation, and scurvy claiming the lives of most of the crew. By the spring of 1620, only Munk and a cabin boy survived, miraculously making their way back across the Atlantic to Denmark in a makeshift barque. King Christian IV established a royal commission to set up a formal Danish colony on Hudson Bay, but the notion was abandoned due to the escalation of the Thirty Years' War (1618 - 1648).Great Freshwater Lake of the Southeast

In Spanish Florida, which extends north to include most of the American Southeast, Lake May, often called Lacus Aquae Dulces or the 'Lake Apalache' is noted. This lake, first mapped by De Bry and Le Moyne in the mid-16th century, is a mis-mapping of Florida's Lake George. While Theodor De Bry, working in 1565, correctly mapped the lake as part of the River May or St. John's River, subsequent navigators and cartographers in Europe erroneously associated it with the Savannah River, which, instead of flowing from the south to the Atlantic (like the May), flowed almost directly from the northwest. Hondius and Mercator took up this error in their 1606 map and, in doing so, inverted the course of the May River, thus situating it far to the northwest in Appalachia. Consequently, 'through mutations of location and size [this] became the great inland lake of the Southeast' (Cumming, 478). This apocryphal cartographic element became one of Le Moyne's most tenacious legacies.Publication History and Census

Vincenzo Coronelli compiled this map in 1688, as dated, simultaneously with this globe gores of the same date. It was not published until at least 1690 and first appeared in an atlas in the 1691 release of the Atlante Veneto. The map is well represented institutionally but is scarce on the market, especially in fine, uncolored original condition, as here.CartographerS

Vincenzo Maria Coronelli (August 16, 1650 - December 9, 1718) was an important 17th-century cartographer and globe maker based in Venice. Coronelli was born the fifth child of a Venetian tailor. Unlikely to inherit his father's business, he instead apprenticed in Ravenna to a woodcut artist. Around 1663, Coronelli joined the Franciscan Order and, in 1671, entered the Venetian convent of Saint Maria Gloriosa dei Frari. Coronelli excelled in the fields of cosmography, mathematics, and geography. Although his works include the phenomenal Atlante Veneto and Corso Geografico, Coronelli is best known for his globes. In 1678, Coronelli was commissioned to make his first major globes by Ranuccio II Farnese, Duke of Parma. Each superbly engraved globe was five feet in diameter. Louis IV of France, having heard of the magnificent Parma globes, invited Coronelli to Paris, where from 1681-83 he constructed an even more impressive pair of globes measuring over 12 feet in diameter and weighing 2 tons each. The globes earned him the patronage of Louis XIV and privileged access to French cartographic information from Jesuit sources in the New World, particularly Louisiana. Coronelli returned to Venice and continued to publish globes, maps, and atlases, which were admired all over Europe for their beauty, accuracy, and detail. He had a particular fascination for the Great Lakes region, and his early maps of this area were unsurpassed in accuracy for nearly 100 years after their initial publication. He is also well known for his groundbreaking publication of the first accurate map depicting the sources of the Blue Nile. At the height of his career, Coronelli founded the world's first geographical society, the Accademia Cosmografica degli Argonauti, and was awarded the official title Cosmographer of the Republic of Venice. In 1699, in recognition of his extraordinary accomplishment and scholarship, Coronelli was also appointed Father General of the Franciscan Order. The great cartographer and globe maker died in Venice at the age of 68. His extraordinary globes can be seen today at the Bibliothèque Nationale François Mitterrand in Paris, Biblioteca Marciana in Venice, the National Library of Austria, the Globe Museum in Vienna, the Library of Stift Melk, the Special Collections Library of Texas Tech University, as well as lesser works in Trier, Prague, London, and Washington D.C. Coronelli's work is notable for its distinctive style, which is characterized by the high-quality white paper, dark intense impressions, detailed renderings of topographical features in profile, and numerous cartographic innovations. More by this mapmaker...

Diego Dionisio de Peñalosa Briceño y Berdugo (1621–1687) was a Spanish colonial soldier and sometime governor of Spanish New Mexico. He was born in Lima, Perú; his early career saw him working within the Spanish Imperial bureaucracy. He rose to the position of Alcalde in the Viceroyalty of Peru, but accusations of misconduct forced him to flee the jurisdiction to evade arrest. He joined the army in New Spain, rising again through the ranks until the Viceroy of New Spain appointed him Governor of New Mexico, a position he would hold from 1661 to 1664. Peñalosa would earn the enmity of Spanish Catholic friars by permitting his domain's Pueblos to retain their cultures and religious practices. This ultimately would see him declared a blasphemer and heretic by Catholic tribunal, and exiled from New Spain in 1665. He then offered his services to James II of England (refused) and then in 1678 to the King of France, Louis XIV (also rejected.) As part of his effort to woo Louis, he provided the French with a manuscript map of New Mexico and the neighboring provinces, notably revealing Spain's silver mines and actively encouraging the French to send him to take the province. He would die in 1687 before any of these plans bore fruit. Learn More...