This item has been sold, but you can get on the Waitlist to be notified if another example becomes available, or purchase a digital scan.

1885 O'Dea View of the Infamous Confederate Civil War Prison at Andersonville

Andersonville-odea-1885

Title

1884 (undated) 38.5 x 58 in (97.79 x 147.32 cm)

Description

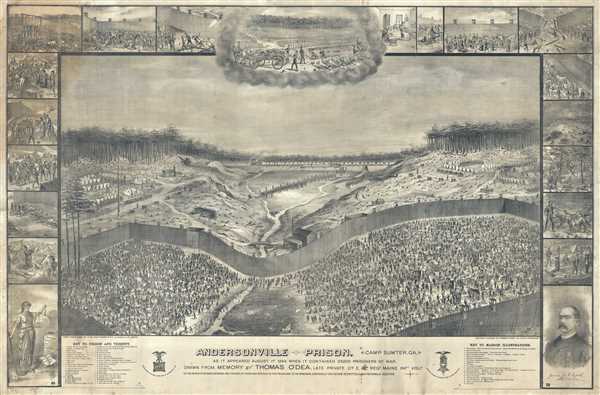

In the 1890 Census of Civil War Veterans and Widows, the single word 'Andersonville' was acceptable in the 'Disability Incurred' category.Over 13,000 prisoners died while incarcerated at Andersonville, with the cemetery occupying the top center section of O'Dea's border. Photographs, novels, movies, paintings, and written memoirs all attested to the unimaginable misery experienced by those incarcerated at Andersonville, but no single work captured the attention of a generation more than Thomas O'Dea's pencil drawing of his personal memory of the camp.

The Only True Representation of the Horrors of Andersonville

Drawn over the course of six years, O'Dea spent his days working as a bricklayer and his nights working on his masterpiece. Frustrated by 'the inaccuracies' of all the photographs and other accounts presented to the public, O'Dea decided to produce his view

hoping in the future that he would be able to supply the deficiencies, correct the misrepresentations of the rest, and give the public a true description of the prison, and a view of the sufferings of its inmates.He drew the entire work from memory, without using an pictures, maps, plans, or scales to 'guide or instruct' him. To skeptics who believed that it would be impossible to create such a detailed work from memory, O'Dea wrote in his History of O'Dea's Famous Picture of Andersonville Prison

To the casual observer, such a thing may be looked upon as absurd, and impossible, that it is impossible after such a length of time for 'memory' to retain such a perfect list and line of details as here portrayed, and that I must have had assistance from some other source to be able to present such a vast combination of characters and situations, in so perfect a manner. Ah, my friends, had you been there, and experienced the sufferings that, in common with thousands of other unfortunates who 'were there', you too, like myself, would have the whole panorama photographed in your memory to remain there to your dying day.Life in Andersonville

The work itself is composed of a central large view that is framed by eighteen vignettes and a portrait of Thomas O'Dea himself. O'Dea strived to illustrate the chaos of living in a prison camp that was constructed to house 10,000 prisoners but was in reality housing 35,000. Known as 'Hell Upon Earth' by those imprisoned in Andersonville, the inmates faced famine, disease, and death on a daily basis. Rations were meager and consisted of cornbread, a few beans, and maybe some pork or bacon, but the meat quickly ran out. A stream, known as 'The Branch' ran through the camp, but not before it ran through two Confederate camps and the prison bakehouse. 'The Branch' was the only water source, which meant it was used for drinking, cooking, and bathing, which meant that clean water was scarce at best. The cleanest water was on the other side of the 'Dead Line', a cord suspended three feet off the ground a few yards from the camp's timber walls. If a prisoner crossed this line in any way, even just reaching across to get some clean water in his cup or dipper, he risked being shot by one of the Confederate guards, stationed every hundred feet in watchtowers along the top of the walls (vignette 2).

No formal housing was constructed at Andersonville. The prisoners were forced to use what they could find or scrounge, leading to most sleeping in holes in the ground and covered by what little cloth they had. The camp covered about thirty-six acres, six of which were completely uninhabitable because they were occupied by a swamp. New prisoners, known as 'fresh fish' arrived by train and were marched the half-mile from the rail line to the camp across an open field. Sketches of prison life frame the large central drawing, providing a focus on both every day and extraordinary events in the lives of the prisoners. The dead were taken out of the camp by cart every morning, after their comrades stripped them of any wearable clothing and carried them to one of the prison's two gates (vignettes 1 and 16). Rations were distributed by the men themselves (vignette 13) and there was a prison police force, which tried and condemned criminals by court martial (vignette 6) and set up an orderly system for accessing a new source of clean water (vignette 14).

O'Dea's masterpiece is not without a political message. Vignette 18 illustrates the 'Goddess of Justice holding the Scales' per O'Dea. He believed that the scales tipped toward those who purchased war bonds to finance the war and away from the soldiers actually fighting in it, which, in his mind, is what led to Grant ending the system of prisoner exchanges and allowing the horrors of Andersonville to happen. O'Dea also provides a 'key to the prison and vicinity' on the left side along the bottom border. This key consists of forty-one different locations, which numerically correspond with points within the central work. Another key on the right side briefly explains each of the nineteen vignettes framing the central work. Sketches of the Official Badge of the National Association of Ex-Prisoners of War and the Official Badge of the Grand Army of the Republic are also included along the bottom border.

This view was drawn by Thomas O'Dea and engraved by T. J. S. Landis on stone. It was lithographed by Henry Seibert and Brother and copyrighted by O'Dea in 1885.

CartographerS

Thomas O'Dea (c. 1849 - March 18, 1926) was an Irish-American remembered for his monumental drawing of the Confederate Prison at Andersonville, officially known as Camp Sumter, Georgia. O'Dea immigrated from Ireland with his family as a young child and settled in Boston. In 1861 at the age of 14, O'Dea wanted to follow his brother George into the Union Navy, but he was turned away and told to 'go home and grow up first'. Two years later, he ran away from home and enrolled as a drummer in the 16th Regiment of the Maine Infantry Volunteers in July 1863. He fought at the Battle of the Wilderness and was captured in May 1864. After short stays in several Confederate prisons, he arrived at Andersonville during the summer of 1864. O'Dea was released from Andersonville on February 24, 1865, and he left ill and emaciated, wearing only a ragged pair of trousers and broken shoes. After months of recuperation, in July he returned home to Boston in the hope of reuniting with his family, but they had disappeared. O'Dea moved to Cohoes, New York in the early 1870s and found work as a mason. Eventually he was elected general secretary of the Bricklayers and Stone Masons Union of America and the Cohoes Board of Supervisors. O'Dea started work on his masterpiece in 1879 after seeing a report that portrayed Andersonville as being orderly. After six years of painstaking work, mostly at night after long days of laying bricks, O'Dea's 4.5 x 9 foot pencil sketch was finished. In the years following completion of his work, O'Dea's drawing gained a place in the nation's psyche. Due to popular demand, O'Dea set up a business and sold examples in various size formats and became a successful businessman. O'Dea married Catharine McGuinness, with whom he had five children. More by this mapmaker...

Henry Seibert (May 17, 1833 - c. 1902) was a German-American lithographer, financier, and businessman. Born in Lauterbach in the Grand Duchy of Hesse to John and Magdalena Seibert. One of seven children (six sons and a daughter), Henry's father John Seibert was a locksmith and machinist by trade and a man of good practical education. John Seibert, believing that a new life in America would afford his growing family with greater advantages than were available to them in Europe, moved the family to Newburgh, New York in 1837 and, in 1845, relocated to Brooklyn. John Seibert died in 1855. Henry, having immigrated to the United States at the age of 4, was educated in Brooklyn public schools and then learned lithography. He formed the lithography firm of Robertson and Seibert in 1852 with Alexander Robertson, which they built into a successful enterprise. James A. Shearman joined the firm in 1859, creating Robertson, Seibert and Shearman, which lasted for approximately a year, but created numerous beautiful chromolithograph views. When both Robertson and Shearman withdrew from the partnership in 1860, Seibert formed the firm Seibert, Wetzler and Company with this brother Jacob and Ernest Wetzler. The following year the partnership changed to Henry Seibert and Brothers and included Henry, Jacob, and Charles Seibert. The Seibert brothers acquired the lithographic firm of Ferdinand Mayer in the early 1870s and continued to operate it as a separate establishment managed by Jacob Lowenhaupt. Jacob Seibert left to open his own firm in 1878, which means Henry and Charles carried on their business under the imprint Seibert and Brother. Henry Seibert essentially retired from the firm in 1880, although he maintained a financial interest. After retiring, Seibert began to associate himself with other business and financial enterprises, gaining a reputation as a careful and sagacious associate and often operating as both a promoter and a directing manager. He became deeply involved in railroad interests, including the Chicago and Eastern Illinois Railroad, the Queens County and Suburban Railroad, the Brooklyn Union Elevated Railroad, the Brooklyn Heights Railroad, and the Brooklyn Rapid Transit Company. He also served, at one time or another, as director of the Mollenhauer Sugar Refining Company, the Nassau Trust Company, the Lanyon Zinc Company, and the Manhattan Brass Company. He also served as director and vice-president of the Minnesota Iron Company during his lifetime. In 1892, New York Governor Flowers appointed Seibert as a commissioner from the state of New York to the Columbian Exposition in Chicago in 1892. Seibert married Emma J. Bergman with whom he had three sons and a daughter. Learn More...

Thomas J. Shepherd Landis (1861 - December 26, 1939) was an American illustrator and artist. Born in Philadelphia, he began working as a lithographer at the age of 14 and eventually attended the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts of Philadelphia. He is best known for his 1916 bird's-eye view of Newark, New Jersey, created to celebrate the 250th anniversary of the founding of the city. Landis was also responsible for the engraving of Thomas O'Dea's bird's-eye view of the Confederate prisoner of war camp at Andersonville, Georgia for the lithographic firm Siebert and Brothers. He also produced drawings for the Pennsylvania Railroad as promotions for their routes to Atlantic City and Cape May. By the end of his career, Landis had held staff positions on Leslie's Weekly and The Toledo Blade. Landis married his wife Lillian R. Landis with whom he had three daughters. Learn More...