This item has been sold, but you can get on the Waitlist to be notified if another example becomes available, or purchase a digital scan.

1561 Ruscelli Mariner's Map of the World

CartaMarina-ruscelli-1561

Title

1561 (undated) 8 x 10 in (20.32 x 25.4 cm) 1 : 108770000

Description

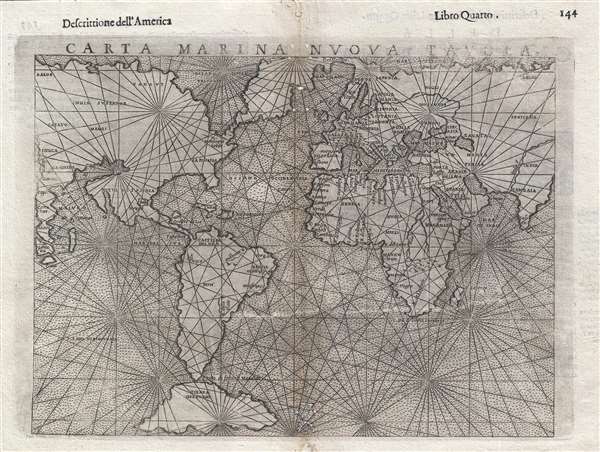

Despite its small size, the map offers much of interest, particularly one of the earliest representations of peninsular California and Florida. Of particular it the connection of North America to both Europe and Asia – dismissing any possibility of either a Northwest Passage or Northeast Passage to Asia. The real cartographic interest in the map is in the Americas, where there is a significant iteration of Verrazano's Sea – the large inlet extending form the Pacific just north of Baja California. Although Ruscelli extends Verrazano's Sea only about half way into the continent, it is in fact based upon the Italian navigator Verrazano's 1524 misunderstanding of North Carolina’s Outer Banks and Albemarle Sound. Verrazano saw the sound from the eastern side of the isthmus and postulated that it must be the Pacific,

. . . where was found an isthmus a mile in width and about 200 long, in which, from the ship, was seen the oriental sea between the west and north. Which is the one, without doubt, which goes about the extremity of India, China and Cathay. We navigated along the said isthmus with the continual hope of finding some strait or true promontory at which the land would end toward the north in order to be able to penetrate to those blessed shores of Cathay …He subsequently mapped a great indentation along the western coast of America starting just north of California and extending nearly to the coast. This great gulf, a precursor of De L'Isle's Mer d'Ouest was a common characteristic of many early maps of the continent. Even in the 1670s, when John Lederer made his famous explorations of Virginia and North Carolina, most colonial settlers believed that the western sea was only about 10 or 15 days inland from the coast.

Ruscelli goes on to connect the northern part of America to Asia where China, Burma, Pegu, Malacca, Sumatra, New Guinea, the Ganges, and even the Philippines are identified if not clearly recognizable. The theory that these continents were joined was at the time common although not universal, nonethless both Ruscelli and Gastladi were supporters.

Tierra del Fuego is also mapped as an extensive landmass but nonetheless insular. This is a significant derivation from most earlier charts which connected Tierra de Fuego to the mythical southern continent of Terre Australis – an idea generally disproved when Francis Drake recognized open sea to the south and intuited the nature of the archipelago.

The style of this map is also noteworthy. Unlike most other maps in Ruscelli's work this is not a Ptolemaic map. Instead the notion of the 'Carta Marina' is derived from navigation portolan charts then circulating in Europe, mostly in manuscript. Like most maritime maps, this map offers little inland detail, and instead focuses on coastlines and is crisscrossed with an elaborate network of rhumb lines – which were handy for navigation. The true 'modern' map is in fact a combination of a Ptolemaic and the Carta Marina.

Ruscelli published this map in the in the 1561 Vincenzo Valgrisi edition of La geografia di Claudio Tolomeo Alessandrino. It was republished without changes in 1562, 1564, 1574, 1598, and 1599.

Cartographer

Girolamo Ruscelli (1500 - 1566) was an Italian polymath, humanist, editor, and cartographer active in Venice during the early 16th century. Born in Viterbo, Ruscelli lived in Aquileia, Padua, Rome and Naples before relocating to Venice, where he spent much of his life. Cartographically, Ruscelli is best known for his important revision of Ptolemy's Geographia, which was published posthumously in 1574. Ruscelli, basing his work on Gastaldi's 1548 expansion of Ptolemy, added some 37 new "Ptolemaic" maps to his Italian translation of the Geographia. Ruscelli is also listed as the editor to such important works as Boccaccio's Decameron, Petrarch's verse, Ariosto's Orlando Furioso, and various other works. In addition to his well-known cartographic work many scholars associate Ruscelli with Alexius Pedemontanus, author of the popular De' Secreti del R. D. Alessio Piemontese. This well-known work, or "Book of Secrets" was a compilation of scientific and quasi-scientific medical recipes, household advice, and technical commentary on a range of topics that included metallurgy, alchemy, dyeing, perfume making. Ruscelli, as Alexius, founded a "Academy of Secrets," a group of noblemen and humanists dedicated to unearthing "forbidden" scientific knowledge. This was the first known experimental scientific society and was later imitated by a number of other groups throughout Europe, including the Accademia dei Secreti of Naples. More by this mapmaker...

Source

- 1561 La Geographia di Claudio Tolomeo Alessandrino, Italian. Venice, Vincenzo Valgrisi.

- 1562 Geographia Cl. Ptolemaei Alexandrini, Latin. Venice, Vincenzo Valgrisi.

- 1564 La Geographia di Claudio Tolomeo Alessandrino, Italian. Venice, Giordano Ziletti.

- 1564 Geographia Cl. Ptolemaei Alexandrini, Latin. Venice, Giordano Ziletti.

- 1574 La Geographia di Claudio Tolomeo Alessandrino, Italian. Venice, Giordano Ziletti.

- 1598 Geographia di Claudio Tolomeo Alessandrino, Italian. Venice, heirs of Melchoir Sessa.

- 1599 Geographia di Claudio Tolomeo Alessandrino, Italian. Venice, heirs of Melchoir Sessa.