This item has been sold, but you can get on the Waitlist to be notified if another example becomes available, or purchase a digital scan.

1856 Viele Plan or Map of Central Park (first map of Central Park, 2 pieces)

CentralPark-viele-1856-2

Title

1856 (dated) 15 x 45 in (38.1 x 114.3 cm) 1 : 3500

Description

The Creation of Central Park

In 1853 the New York State Assembly passed the historic legislation that would lead to the creation of the first planed urban recreation area in the United States - New York City's Central Park. With the grounds for the future park officially delimitated, the years that followed were marked by a struggle between city officials and the 'rapacious occupants of the cabins which deface the ground.' The lands designated for the park were, for the most part, rocky swampland, and were the home of some 1500 disenfranchised individuals: former slaves, poor immigrants, vagrants, and various undesirable businesses such as 'piggeries.'Enter Egbert Viele

While the work of acquiring the land and displacing the current residents fell to the City Council and New York Police Department, the work of preparing the grounds fell to the radical civil engineer Egbert Ludovicus Viele. Viele, who was completing a topographical survey of New Jersey under William Kitchell, was assigned to be the first 'engineer-in-chief' of the Central Park Commission. Viele held the radical though not unfounded belief that epidemic level disease evolved from excess moisture in the soil. His topographical experience combined with his passionate advocacy for open public spaces, proper drainage, and clean air, made him the ideal force to define New York City's proposed Central Park.Creating the Maps

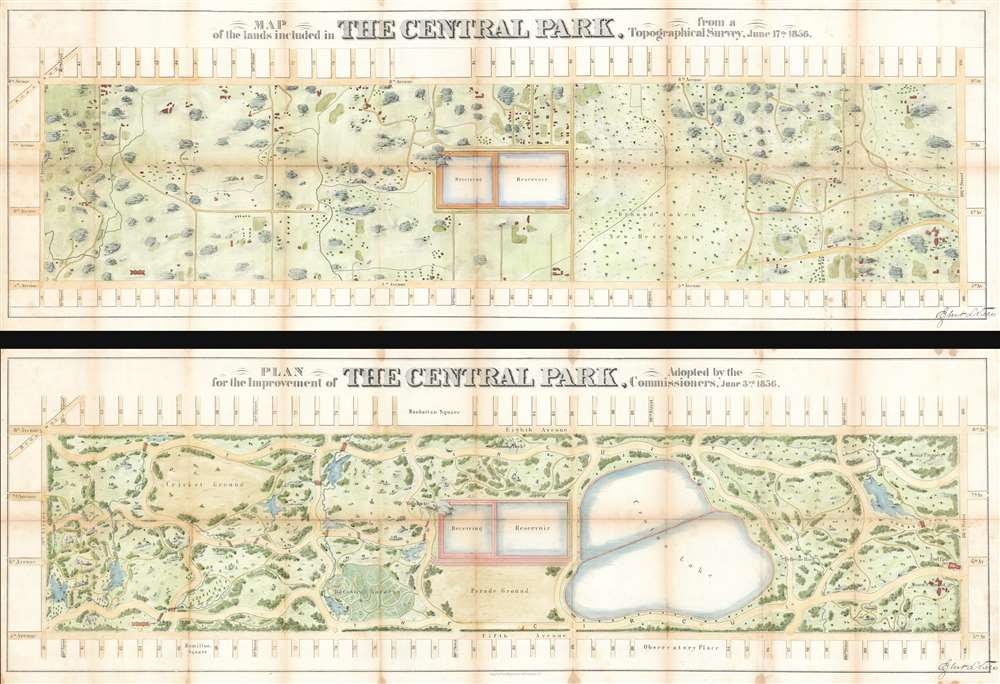

By 1856, with most of the former inhabitants cleared out, Viele assembled a team to survey and define the future park. He divided the reserved lands into five sections to which he sent separate teams to survey, identifying every standing building, rock, hill, stream, valley, road, and pasture. The result is the upper to the two maps currently offered. This is a topographical survey of the park lands as they appeared just prior to the park's construction. Viele identifies various dwellings, including the African-American community on East 83rd Street known as Seneca Village, the old 'Receiving Reservoir' (currently the Great Lawn), the proposed site of the new reservoir (currently the Old Croton Reservoir), and the Mount St. Vincent Convent - which was subsequently relocated to the Bronx, where it still exists. This important plan, not only enabled Viele to provide the city council with cost estimates for preparing the land, it also served as the basis for all subsequently proposed plans for Central Park, including Viele's own plan, discussed below, and the ultimately victorious Olmsted and Vaux plan.Seneca Village

Seneca Village, which stretched from West 82nd Street to West 89th Street, was a community created within the bounds of what became Central Park by African Americans and Irish and German immigrants. Seneca Village began in 1825 when John and Elizabeth Whitehead, who owned the land in the area, subdivided the land and sold it as 200 lots. The first buyers were African Americans, and by the mid-1850s, Seneca Village had grown into a community of fifty homes, a school, three churches, and two cemeteries. Many of Seneca Village's residents owned their property. In 1821, New York State law stated that, in order to vote, an African American man had to own at least $250 in property and hold residency for at least three years. 100 black New Yorkers were eligible to vote in 1845 under this law, ten of which lived in Seneca Village. With the advent of Central Park, Seneca Village was siezed by the city through eminent domain. The city compensated the landowners, but many complained that their land was undervalued. Unfortunately, very little is known about where the residents of Seneca Village went after they were forced to leave their community.The Second Map

The second map, the lower of the two illustrated above, is the first actual plan of Central Park. Central Park is famous for the historic 1857 design competition that catapulted Frederick Law Olmsted from a relatively obscure garden designer to the world's best known landscape engineer. However, one year before this contest, Egbert Viele had already produced his own design for the Central Park, what he considered a 'harmonious blending of all that is beautiful in light and shade, in color, size and shape.' He attached the design to his topographical map, both of which accompanied his report to the city council. As the engineer-in-Chief of the Central Park Project, Viele had an enormous impact on the overall design and layout of the park. While Viele's plan of the park is instantly recognizable, a closer examination will reveal that this is not, in fact, the modern Central Park. Nonetheless, this map had a profound influence on most subsequent park designs as it set various legislative directives that all entries to the Central Park Design Competition were required to comply with. These included four or more park transverses, a large parade ground, various children's play areas, a fountain, a skating pond, and a lookout tower, among many other features. Most of these elements made their first appearance on this map by Viele.Viele's Influence on the Design Competition

Although the plan submitted by Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux, nearly a year after the publication of Viele's Plan for Central Park, was the ultimate winner of the Central Park Design Competition, all competitors would have had the opportunity to examine both of these important maps. While there are a number of notable differences - for example most latter plans of Central Park adopted the proposal to extend the park to 110th street, Viele's ended at 106th - it is no trick that the Viele Plan is instantly recognizable as Central Park. The groundwork established here by Viele, almost as much as Olmsted's brilliant vision, defined the modern day Central Park.Constructing Central Park

The formal construction of Central Park began two years later in 1859. The creation of Central Park, which was to consist of some 800 acres of public forest, pathways, promenades, lakes, bridges, and meadows, was a seminal moment in civic urban design. The park itself was designed as a whole with every tree, pond, and bench meticulously planned. Historian Gloria Deak writes,There was a staggering amount of work to be done to transform the area into a blend of pastoral and woodland scenery. This involved the design and construction of roadways, tunnels, bridges, arches, stairways, fountains, benches, lamp posts, gates, fences and innumerable other artifacts. It also involved the supervision of an army of about five thousand laborers…Olmsted, to whom most of the credit goes, insisted on seeing the multidimensional project as a single work of art, which he was mandated to create. For this purpose, he ventured to assume to himself the title of ‘artist.'Today, because of Viele, Vaux, Olmsted, and others, New Yorkers, ourselves included, have the privilege of enjoying what is, perhaps, the finest example of a planned urban public recreation area in the world.

Publication History and Census

These maps were created by Egbert Viele and published in the First Annual Report on the Improvement of The Central Park, New York in 1857. Six examples are cataloged in OCLC and are part of the institutional collections at the Brooklyn Historical Society, the New York Public Library, Columbia University, the New York Botanical Garden, Cornell University, and the Library of Michigan.Cartographer

Egbert Ludovicus Vielé (June 17, 1825 - April 22, 1902) was an American civil engineer, cartographer, businessman, and politician active in New York City during the second half of the 19th century. Born in Saratoga County, Vielé attended the United States Military Academy at West Point. Graduating in 1847, he was commissioned as a brevet second lieutenant in the 2nd United States Infantry. He served in the Mexican-American War before resigning form military duty to pursue a career as a Civil Engineer in New York City. When the call came to plan New York City's Central Park in 1856, Vielé was established as Engineer-in-Chief of the project, and it was he who set down the guidelines by which Vaux and Olmstead ultimately planned the park. He held a similar position as engineer of Prospect Park, Brooklyn from 1860. It was most likely during his tenure with the park commissions that Vielé developed his theories connecting compromised natural drainage with sanitation and infectious disease. Vielé's great cartographic masterpiece, the Topographical Map of the City of New-York, euphemistically known as the 'Vielé Map' or 'Waterways Map' evolved out of the notion that epidemic level disease evolved from excess moisture in the soil. He contended that, as New York City expanded northwards, paving over stream beds and leveling out natural drainage channels, the underground waterways would stagnate and lead to plague or worse. Though intended for the purpose of urban planning, the Vielé Map's (as it came to be known) greatest legacy is as a construction tool. To this day, contractors, architects, and engineers consult the Vielé map to determine if unseen subterranean waterways need to be taken into account when preparing building foundations. He was elected as a Democratic representative to the Forty-ninth Congress (March 4, 1885 – March 3, 1887) and ran unsuccessfully for re-election in 1886. He was heavily involved in New York real-estate interests, but also owned shares of mining and railroad companies as far off as Colorado. Vielé died in April of 1902 and was buried in an elaborate Egyptian Revival tomb at West Point. Legend tells that Vielé, paranoid that he would be buried alive, an unfortunate but surprisingly common problem in the 19th century, installed a buzzer inside his coffin that would allow him to ring the school's commanding officer should the need arise. Apparently, it did not. More by this mapmaker...