This item has been sold, but you can get on the Waitlist to be notified if another example becomes available, or purchase a digital scan.

1947 White Cartoon Original Art, Chinese Civil War, Failed Peace Talks

ChineseCivilWar-white-1947

Title

1947 (undated) 11 x 10 in (27.94 x 25.4 cm)

Description

A Closer Look

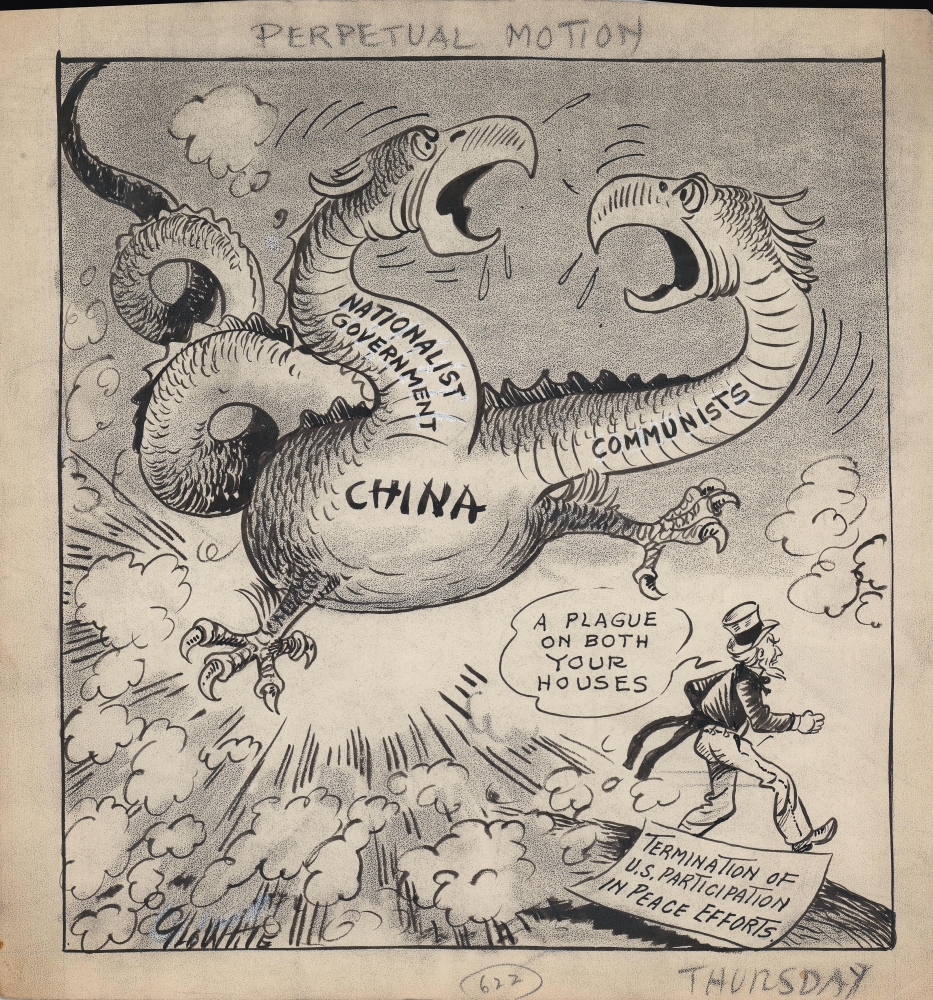

The two-headed dragon represents the Nationalist government, led by Chiang Kai-Shek and the Kuomintang (KMT / Guomindang / GMD), and the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), led by Mao Zedong. In the cartoon, the two heads prepare for a fight while Uncle Sam stamps away from the fracas, having given up on efforts to negotiate a peace.The Marshall Mission and the Chinese Civil War

The context of the cartoon is the failed diplomatic mission to China led by General George C. Marshall, renowned for his more successful wartime service and postwar reconstruction efforts in Europe. America's crisis in China had been brewing for years, and ultimately resulted from insurmountable enmity between the CCP and GMD going back to the 1920s, as well as deep discomfort with Chiang Kai-Shek's regime.Although the two parties and the militaries associated with joined a 'united front' against Japan in the World War II (Second Sino-Japanese War), they deeply distrusted each other, barely coordinated their efforts, and even fought skirmishes against each other while also fighting Japan. When the war against Japan suddenly ended in August - September 1945, both sides began jockeying for position to prepare for a outright civil war.

On paper, the Nationalists had a distinct advantage, including a degree of U.S. military support which included flying troops from their wartime base of Chongqing to cities around China to receive the surrender of Japanese forces (rather than letting the Communists handle the surrender and receive badly needed weapons). However, Chiang's forces had taken a beating during the eight-year long war with Japan, including a large Japanese offensive (Operation Ichi-go) in the closing months. Chiang's large army was an amalgamation of warlord outfits that only followed orders when it suited their interests. Politically, the regime was also deeply corrupt and disorganized, simultaneously weak and repressive. Economically, the task of establishing a stable currency, let along rebuilding the country, was daunting.

Moreover, Chiang's U.S. support was tenuous. A string of generals and diplomats had reported to Washington that Chiang was an incompetent dictator and fantasized openly about overthrowing his government. American journalists, diplomats, and even some military figures had been duped by CCP propaganda efforts that deemphasized their revolutionary tendencies and portrayed themselves as democratic nationalists.

Conversely, the Communists were low on military hardware but had spent the war perfecting political mobilization, guerilla warfare, and propaganda. Mao had purged all his potential rivals while also cultivating capable lieutenants who trusted his leadership. Although disagreeing with the Soviets on the pace and timing of revolution, the two pursued tacit cooperation, arranging for the CCP to establish a base of operations in Manchuria, which the Soviets occupied at the end of the war against Japan.

As for their part, George Marshall and other Americans in China spent 1946 banging their heads against the wall, seeking a compromise that neither the GMD nor CCP wanted. However, both parties had an interest in appearing open to negotiation; the GMD so as not to lose American support entirely and the CCP so as not to push the U.S. to more heartily back Chiang's regime. Significantly, the U.S. suspended military sales to Chiang's military in July 1946, in part to help broker a ceasefire but also due to dissatisfaction with Chiang. Eventually, in January 1947, Marshall left China in frustration and the civil war fully resumed. In the following years, a range of hardline anti-Communists rather unfairly blamed Marshall and other Americans involved in the negotiations for 'losing China.'

Although Chiang's armies scored early victories, the guerilla warfare tactics of the Communists led to cities being surrounded by a hostile countryside, to paraphrase a quote by Mao. Combined with a worsening economic situation, Chiang's armies and regime began to disintegrate. By the end of 1948, the Communists controlled Manchuria and afterwards went from victory to victory, expelling Nationalist forces to Taiwan and a few other isolated outposts by the end of 1949.

Publication History and Census

This cartoon was drawn by George White for the Tampa Morning Tribune, most likely in January 1947. It is an art manuscript from the estate of George White.Cartographer

George White (1901 - March 7, 1964) was born in Grand Rapids, Michigan and relocated to Tampa with this family in 1915. White studied art under Tampa artist Walter Collins and began work as a commercial artist at the Tampa Morning Tribune in 1928 and by 1934 was a regular cartoonist at the Tribune. Rather unconventionally, the paper featured his cartoons on the front page. His work displays the evolving course of America's domestic and geopolitics from the interwar period, through the Second World War, and into the Cold War More by this mapmaker...