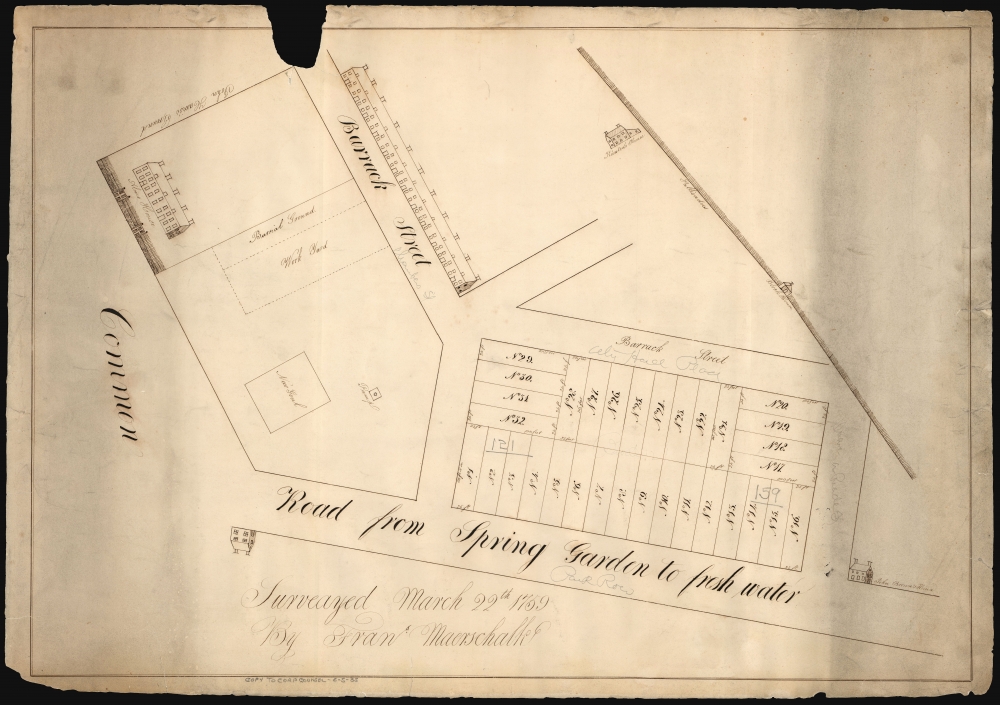

1811 / 1759 Francis Maerschalck Survey from New York's City Hall Park to Park Row

CityHallPark-maerschalk-1811

Title

1811 (dated) 18.25 x 26 in (46.355 x 66.04 cm) 1 : 400

Description

A Closer Look

The survey is oriented about 60° to the northwest; its detail is confined to the northeastern part of what is now City Hall Park. Its southern limit is the Common, whose northern extent is in line with modern-day Murray Street. (The street is not named; indeed, its eastern limit was Broadway, which is beyond the scope of the present survey whose western limit is marked 'John Harris' Ground.' This is roughly the location, somewhat east of Broadway, of where the Bridewell would later be constructed.) Its southeastern boundary is Park Row; here identified as 'Road from Spring Garden to fresh water'. Although doubtless, when this survey was copied, it was known interchangeably as Chatham Row or Chatham Street. The north is delimited by the city's palisade wall. The surveyed area is divided further by a handful of streets, two of which were named 'Barrack Street' in the original, inked hand; three small connecting streets are not here named.In addition to the city palisade, the survey places municipal and military structures: the almshouse, the new city goal (sic), and the new barracks. Several free-standing houses are depicted, two of which are named. Most prominently, a block of land broken into 32 lots for dense development has been plotted out. It is probably the survey of this land that is the specific object of this piece - both judging by the detail of the map itself and the title on the verso, 'Land on Chatham Street.'

Elements of the 1755 Maerschalk Plan

Maerschalk's 1755 'A plan of the city of New York from an actual survey' provides a useful starting point for the present work. Not only do the two share an author, but in the way these two pieces, just four years apart, illuminate the rapid changes occurring both in this specific area and those implied for the rest of the city. The 1755 map marks the location of the city common, the almshouse, and the city palisade. The almshouse itself is roughly equidistant from Broadway and the 'High Road to Boston,' which corresponds with Chatham Row/Street. While the earlier map delineates a broad lot inclusive of the alms house, there are no individual roads bisecting the land spanning from the Common to the palisades. Separate houses are shown, unnamed, along the Palisade and along the 'High Road.' All of these features can be identified on the 1759 map.Maerschalk's 1759 survey includes an array of features not appearing on the 1755 plan. A few of these may simply have been too specific to detail on a plan of the whole city, but others are included, which are known not to have existed when the 1755 map was surveyed and which certainly would have been included had they been there. None of the streets within the bounds of the survey - Barrack Street, nor the unnamed Tryon Row, Barley Street, or Potters Hill - appear on the 1755 plan.

In the southwest corner of the surveyed area (the upper left corner) New York's almshouse appears as it does on the 1755 plan. Here, it is shown along with its work yard and burial ground: this latter was plotted out in 1757 and was a new feature at the time this survey was made. (It is not to be mistaken for the 'African Burial Ground,' which was several blocks to the north between Chambers and Duane Streets - outside the Palisade, that is to say, outside of city limits.) To the east of the almshouse is the New Goal (sic), which is the new jail. This had just been completed in 1759, so its absence on the 1755 plan is not surprising. Just northeast of that, a freshwater pump is marked.

North of the almshouse (just south of the level of Warren Street, close to the present-day 'City Hall Park Path') is Barrack Street, parallel to the long building pictured here, which gives the street its name. The barracks were constructed in 1757 to house an astonishing 800 British regulars in order to relieve pressure on citizens who would nevertheless be compelled to quarter soldiers in their homes.

The most current feature of this survey - and raison d'etre - are the surveyed lots along Chatham Street. The block was bounded by Tryon Row to the south and Duane/Barley Street at the northeast (neither street here named), and the northeast arm of Barrack Street parallel to Chatham (this street, as early as 1767, was named Augustus Street). This was divided into 32 lots, each 100 feet by 25 feet. No notes indicate ownership of these; the survey may have been produced before their sale. The inclusion of the pump by the new jail may have been to emphasize the new block's proximity to fresh water; the position of these properties in relation to the barracks may have been seen as an incentive to open businesses to service the soldiers.

The Following Printed Record

Comparison of Maerschalk's 1755 plan and 1759 survey with the next stages of the printed mapping of the city is fascinating. The 1766 Montresor shows the almshouse, the 'goal' (sic), and the barracks. The surveyed block is presented similarly to the other built-upon blocks, bounded by a truncated Barley Street and an isolated Augustus Street. A house that may correspond to Kiersted's house is drawn in, though not named. On the north side of Augustus, the street is faced with buildings.Conspicuously absent from the Montresor is any indication of the palisades that form the city limits on Maerschalk's works. The placement of the new block on the 1759 Maerschalk virtually touched the Palisade. The new development indicated on the Montresor-both the structures north of Augustus and the development north of Warren Street further west would have required dismantling the wall. Maddeningly, while Stokes is punctilious in reporting the construction of the Palisade in 1746, he is silent on its dismantling. It is not credible that even the harried Montresor would have missed such a feature in his survey, so it is likely that it came down before 1766. It is easy to imagine that as soon as the lots along Chatham Row marked in the present survey sold, there would have been significant pressure to deconstruct the Palisade in anticipation of further development.

A 19th Century Copy

The survey is prominently credited to city surveyor Francis Maerschalk (1704? - 1776) and dated March 22, 1759. The occasion for the execution of the survey - the planned development of the Chatham Row block - appears to be clear. This particular manuscript is, however, a copy of that lost original: the paper is woven, which Maerschalk would not have had in his lifetime and which was not widely available in America until the early 19th century. Further, scrutiny of the plan reveals fine pinholes at the intersection of virtually every line, a fascinating artifact of the copying process. (The original sheet would be laid over a blank sheet, and pins were driven through both sheets at every intersection on the original. By connecting those points with a straightedge on the new sheet, a precise 1:1 copy of the original could be produced. In this case, not only the streets and lots show evidence of this copying process, but also the depictions of houses, including chimneys and windows. Thus, we can conclude that Maerschalk's survey included the structures neatly copied here.We know from the city surveyor's stamp on the verso that this manuscript entered the collection of City Surveyor Edwin Smith at some point during his tenure, but the specific author of this copy is left to conjecture. There is no signature. It could arguably have been an early work of Smith's, William Bridges, or Evert Bancker. Historical circumstances, however, encourage us to suspect a date of 1811 or 1812 for this copy to have been relevant. Stokes (p. 489) reported a fire in this area on May 19, 1811:

…a fire broke out in Lawrence's coach factory in Chatham Street, and raged for about three hours, destroying nearly one hundred houses in Chatham, Augustus, William, and Duane streets. It was said that the city had never been in such danger since the great fire of 1776. The cupola of the Gaol, the roof of the Scotch Church, on Cedar Street, and the steeple of the Brick Church were on fire. The Gaol was saved by the activities of the prisoners, and the Brick Church by a sailor, who climbed the steeple by means of the conductor (lightning rod) and beat out the flames…A fire, starting in the Chatham Row/Duane Street vicinity and spreading to ignite buildings as far downtown as Cedar Street, must have completely gutted the block plotted here, and the document would have been relevant for establishing ownership.

It appears that in the wake of the fire, the city moved to untangle some of the streets of this neighborhood. Until 1811, Chambers Street ended at Centre Street, the unnamed street extending from Barracks Road towards the Palisade. In 1811, after the fire, Chambers was extended to meet Chatham Street at its intersection with Duane. To do so, it was required to be run through the block of lots between Augustus and Chatham, which was an easier project after it was burnt to the ground. By 1850, Centre Street extended to City Hall Square, which was established between Ann Street and Tryon Row along Chatham/Park Row in 1848. The Gaol - which became a debtor's prison following the Revolution - was reconstructed in 1830 to become the city's Hall of Records.

A Vanished Neighborhood

New York builds upon its own bones everywhere, a literal truth here. (Archaeological studies of City Hall Park initiated in 2001 would, among other things, find human remains from the almshouse's burying ground.) The barracks and the gaol were razed in 1790 in the wake of the Revolution. The almshouse and its grounds shown here made way for the new city hall. The Chatham Row block, now on the southeast side of Centre Street, is now occupied by the David N. Dinkins Manhattan Municipal Building.Later Pencil Notations

A later hand gamely attempted to identify these streets with modern ones, with limited success. That writer correctly labels 'Road from Spring Garden to fresh water' as Park Row, but the unnamed Duane Street has been penciled in with the hedging 'Duane or Reade Street' (at the time of the survey, it was likely not named at all, and in 1797 it was known as Barley Street.) The west arm of Barrack Street is incorrectly conflated with Chambers Street, but its northeastern branch is correctly identified with City Hall Place (which was between 1767 and 1834, known as Augustus Street). In the margin, a 20th-century hand notes 'Copy to Corp Counsel - 6-5-35.' Whether this specific copy was the one sent or a copy was made, it is remarkable that the present survey was still considered relevant in 1935. (Robert Moses was redesigning the park, much to the consternation of the Daily News who railed 'Moses Ousts Civic Virtue from New City Hall Park.'Publication History and Census

This survey was drawn by Francis Maerschalk on March 22, 1759. The present work is a fair copy executed in the early 19th century, probably 1811 or 1812, in the wake of the fire that tore through this part of the city. We find no trace of either the 1759 original, the 1935, or any other surviving copy of this survey.Cartographer

Francis Maerschalk (1704? - 1776) held a long tenure as City Surveyor in colonial New York, of which city he appeared to have been a native. Nothing is known of his early life and instruction; he became a member of New York's Dutch Reformed congregation on August 21, 1723; he was married at that church to Anneke Lynsse on April 22, 1727. He was appointed City Surveyor in 1733. Between 1744 and 1754, he executed the surveys that would be incorporated in the so-called Maerschalk Plan of New York, which was published by Gerardus Duyckinck in 1755. Heis understood to have surveyed the Blooomingdale Road in 1760, and performed many commercial and civic surveys of other specific areas of the city. His plan of the city is the only printed work attributed to him. More by this mapmaker...