This item has been sold, but you can get on the Waitlist to be notified if another example becomes available.

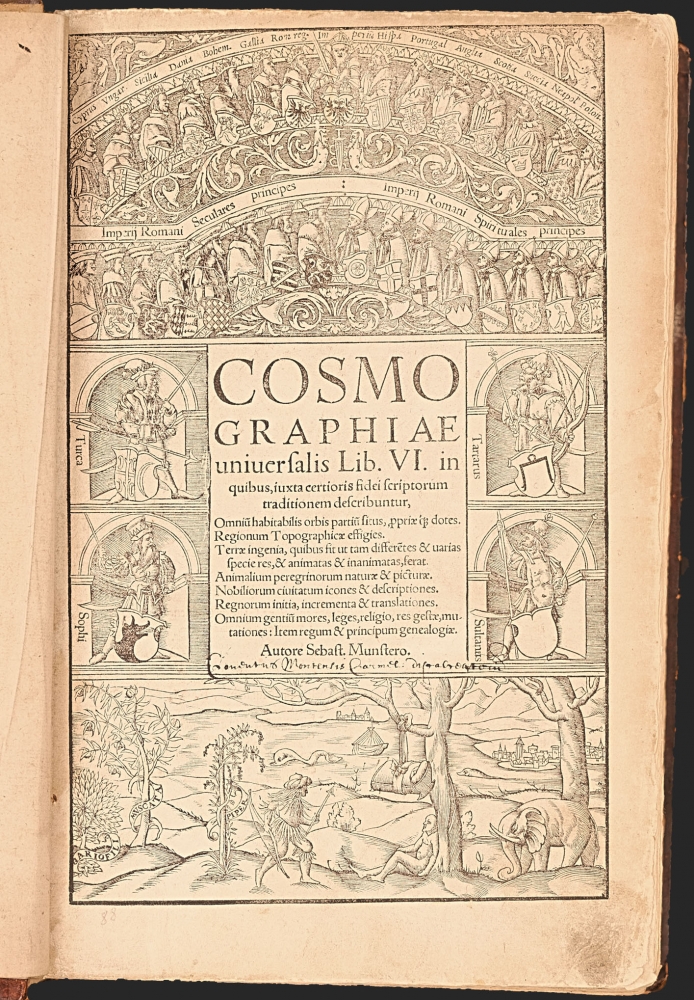

1550 Sebastian Münster Cosmographia: the first Latin Edition

Cosmographia-munster-1550

Title

1550 (dated) 13.5 x 9.25 in (34.29 x 23.495 cm)

Description

That the book retained an audience long after its publication is attested to by the present example: almost two hundred and fifty years after its publication, it fell under the scrutiny of a Catholic censor, expurgating passages deemed harmful to the Church, the Papacy, and the modesty of the presumably Catholic reader.

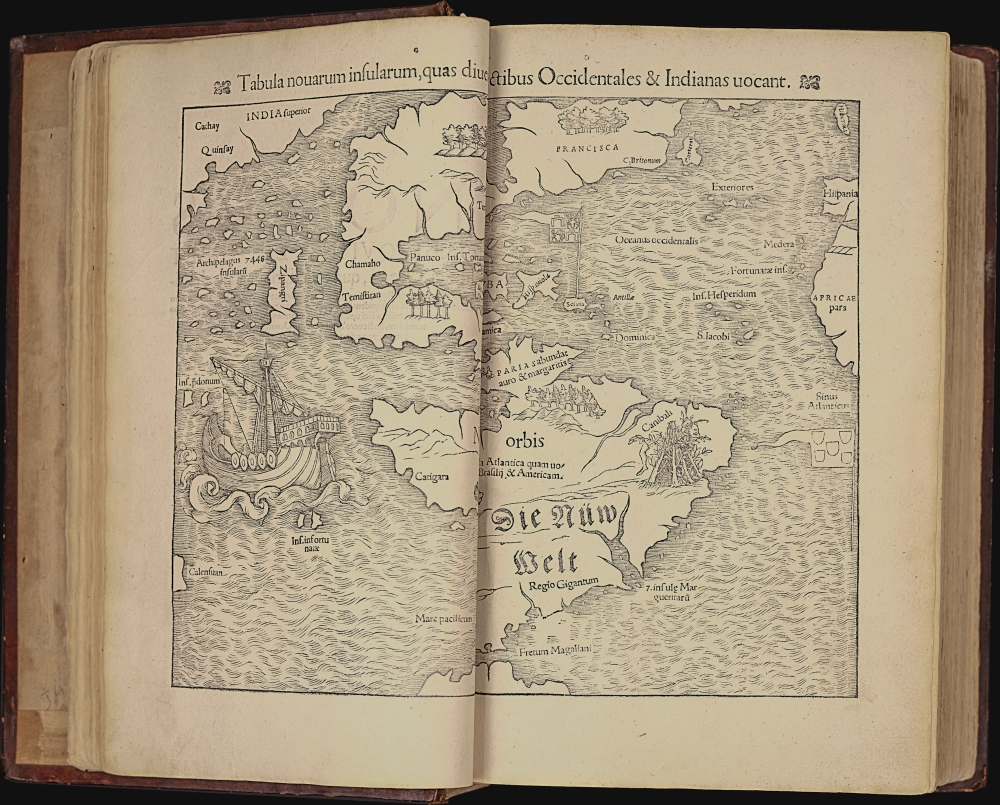

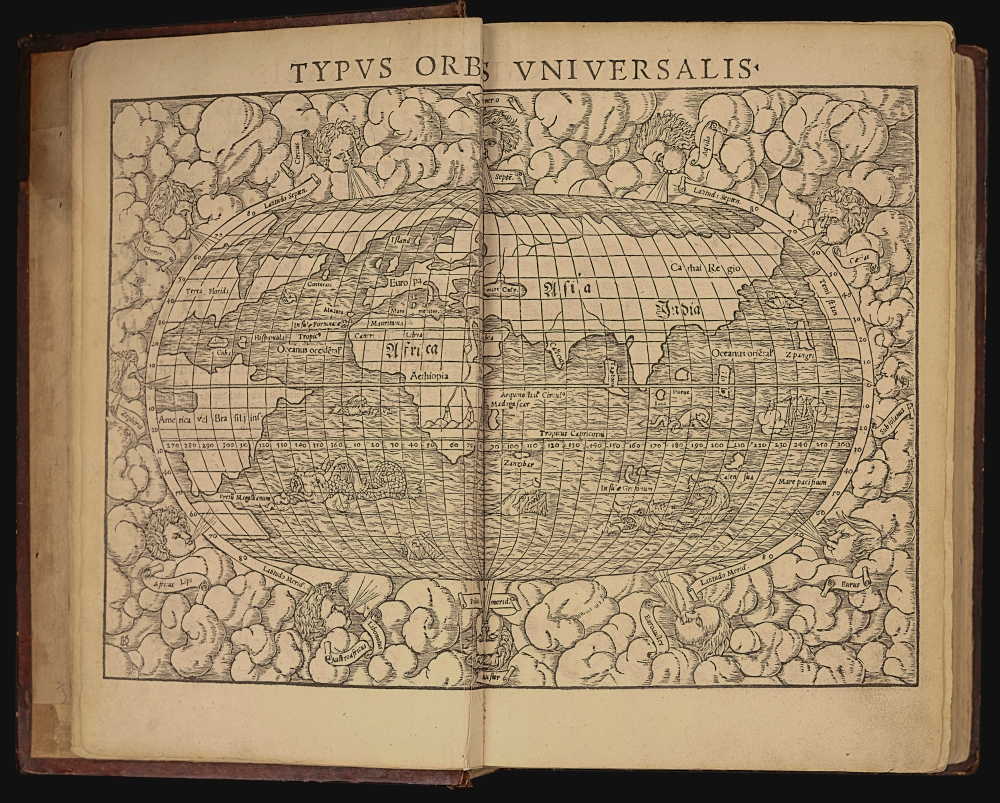

The World Presented Anew

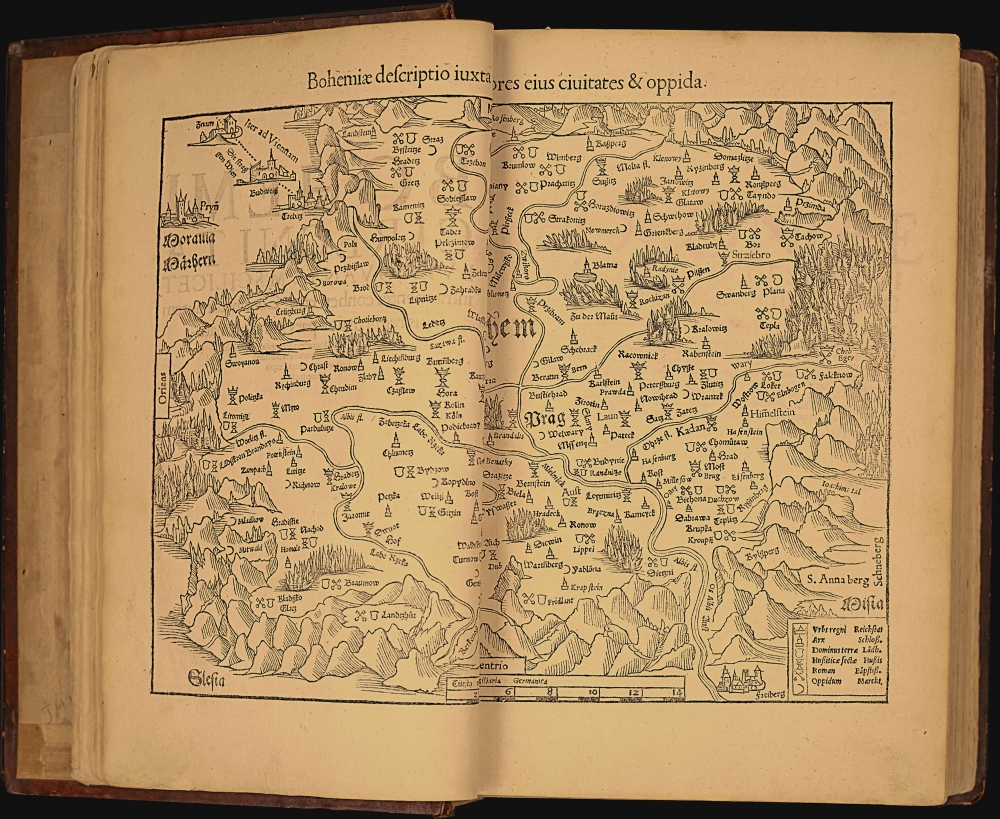

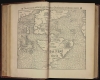

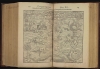

Münster's work benefited broadly from his own expertise as a geographer, mapmaker, historian and astronomer, but his efforts as a correspondent shone in Cosmographia. His letter-writing campaign spanned the Holy Roman Empire and reached abroad to scholars across Europe. Münster's genius was, to a large extent, his ability to source maps, views and descriptions from contemporary sources near to their subjects. The result is that a disproportionate number of the images and reports appearing in this work are the earliest acquirable maps and views of what they depict. For example, the map of France is a neat reduction of the unacquirable 1525 map of France by Oronce Finé, the first such drawn by someone who lived there; the Poland/ Hungary is derived from the lost 1525 map of Bernard Wapowski. The view of Edinburgh (the first printed depiction of that city, and the first of any city of the British Isles to appear in Münster's work) was given by Alexander Ales, a Scot emigre. Many of these treasures Münster won by his lifelong labor as a letter writer, pest, and guilt - tripper. When his requests for maps and views were not met, he would complain in the body of his text. For example, his short description of Besançon ends most curtly: 'I have nothing more to write here about this city, since despite my frequent requests, nothing has been sent to me.'Adding to the Cosmographia

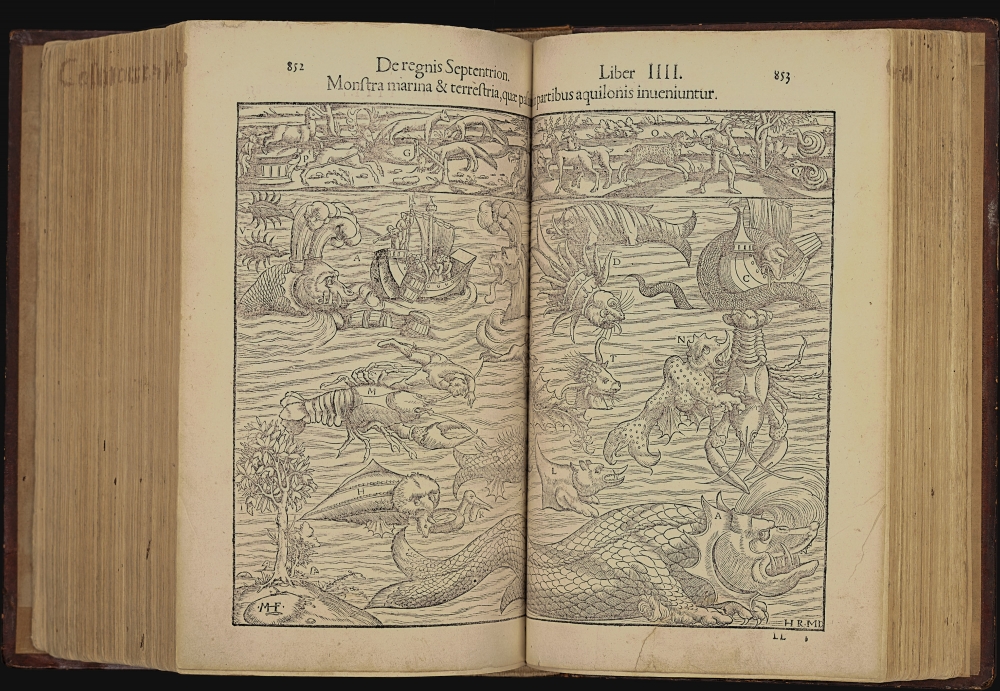

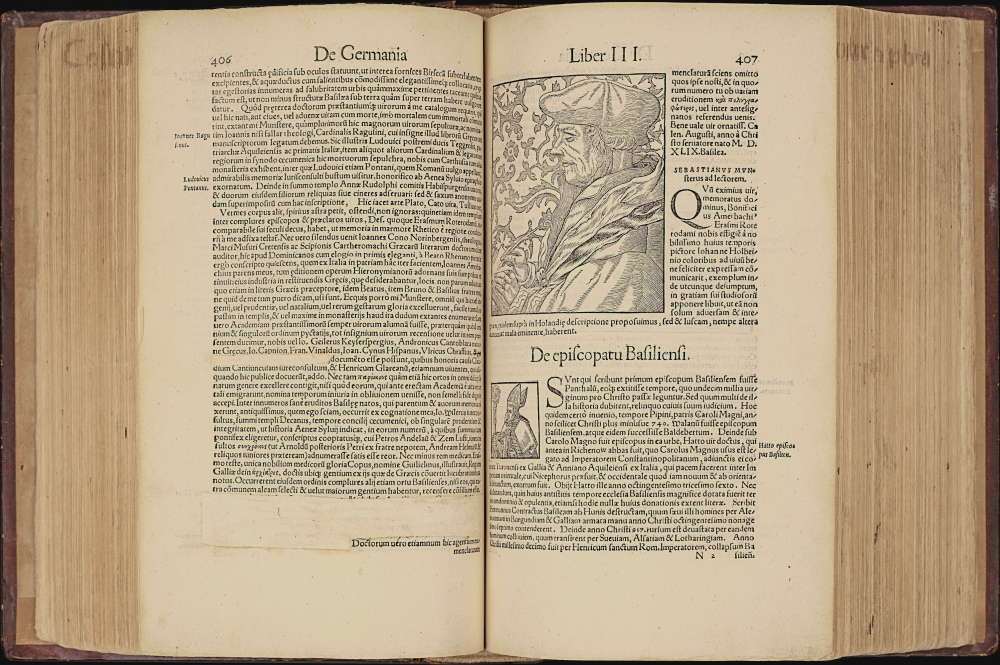

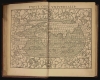

Dozens of the woodcuts gracing this book did not appear in Münster's work prior to 1550. Münster constantly labored to build the work until his death by plague in 1552, both adding to the text as well as ordering the production of improved city views and decorative woodcuts. In particular, the publication in 1548 of Johannes Stumpf's 1548 history of Switzerland - a beautiful and elaborately illustrated work - spurred Münster to introduce more and finer decorative woodcuts to his magnum opus. 1550 saw the addition of a wealth of full-sheet and folding city views, as well as illustrations such as Münster's famous depiction of the sea monsters thought to inhabit the northern oceans. Many of these woodcuts were composed by the Swiss artists and formschneiders David Kandel, Hans Rudolf Manuel Deutsch, Jacob Clauser, Heinrich Holzmüller, and Christoph Schweicker, but other anonymous artists were clearly engaged in the mammoth work.Revealing the Wonders of the World

Although sometimes referred to as an atlas, Münster's magnum opus was a much broader project. An atlas is first and foremost a collection of maps, and need not rely on any text at all; Cosmographia represented an attempt to describe, as the name suggests, the entire cosmos. It included descriptions of flora, fauna, geological and astronomical observations, historical notes, and cultural (some might even say anthropological) commentary. Part of Münster's goal with this work was to present a distinctly German competitor to the renaissance in geography that was already underway in Italy, but Münster's motivation had a strong religious component. Münster's efforts as a Hebraist and teacher of Biblical languages were intended to provide his students with a more direct connection to scriptural revelation. Cosmographia, meant to present all the whole world within a single tome, was intended to provide his students an understanding of the revelation of G_d's work observable in His creation.Evidently a Dangerous Work

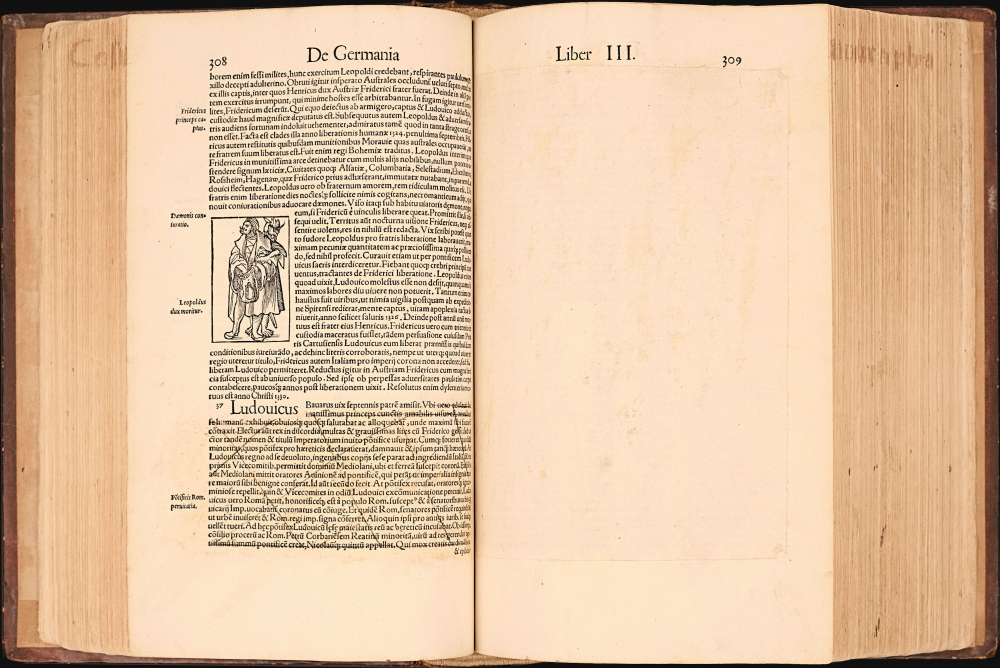

Münster's book is predicated on the notion, a novel one in the 16th century, that ordinary people could understand the world without mediation: it was a book produced in the same humanist intellectual movement that produced vernacular Bibles. Münster had left the Catholic Church in 1529, and was a Protestant for the rest of his life. For this reason, his name would always appear in editions of the Catholic Index librorum prohibitorum. Although Cosmographia was not singled out in the 1786 Index - as was his Psalterium Hebraicum, Graecum, Latinum cum Annotationibus - the mere appearance of his name would have been enough to bring the book under a censor's scrutiny, as this example did in 1796. The censor - an 18th century judge, Nicolas de Freising - singled out passages that criticized the Papacy (or could be construed to do so) and references to important figures of the 16th century Reformation. In Münster's discussion of the long history of scholarship in his home city of Basel, the censor has eliminated mentions of the humanist scholars Simon Grynaeus, Hieronymus Gemuseus, and Sebastian Brant (author of the satire, Ship of Fools.) Other seemingly innocuous passages caught the de Freising's attention: for example, a comment that Greek Orthodox priests were allowed to marry. The censor signed his work, and dated it: August 3, 1796. Happily, de Freising's pen, paste and paper were not employed on the maps or woodcuts of this work, with the exception of the depiction on page 154 of the Sybils, whose nakedness the censor covers.Publication History and Census

Munster's Cosmographia was a popular work, and as many as fifty thousand were printed; of this edition, about fifty survive in institutional collections in varying states of repair. We see examples of this edition appearing in nine auction records reaching as far back as 1894.Cartographer

Sebastian Münster (January 20, 1488 - May 26, 1552), was a German cartographer, cosmographer, Hebrew scholar and humanist. He was born at Ingelheim near Mainz, the son of Andreas Munster. He completed his studies at the Eberhard-Karls-Universität Tübingen in 1518, after which he was appointed to the University of Basel in 1527. As Professor of Hebrew, he edited the Hebrew Bible, accompanied by a Latin translation. In 1540 he published a Latin edition of Ptolemy's Geographia, which presented the ancient cartographer's 2nd century geographical data supplemented systematically with maps of the modern world. This was followed by what can be considered his principal work, the Cosmographia. First issued in 1544, this was the earliest German description of the modern world. It would become the go-to book for any literate layperson who wished to know about anywhere that was further than a day's journey from home. In preparation for his work on Cosmographia, Münster reached out to humanists around Europe and especially within the Holy Roman Empire, enlisting colleagues to provide him with up-to-date maps and views of their countries and cities, with the result that the book contains a disproportionate number of maps providing the first modern depictions of the areas they depict. Münster, as a religious man, was not producing a travel guide. Just as his work in ancient languages was intended to provide his students with as direct a connection as possible to scriptural revelation, his object in producing Cosmographia was to provide the reader with a description of all of creation: a further means of gaining revelation. The book, unsurprisingly, proved popular and was reissued in numerous editions and languages including Latin, French, Italian, and Czech. The last German edition was published in 1628, long after Münster's death of the plague in 1552. Cosmographia was one of the most successful and popular books of the 16th century, passing through 24 editions between 1544 and 1628. This success was due in part to its fascinating woodcuts (some by Hans Holbein the Younger, Urs Graf, Hans Rudolph Manuel Deutsch, and David Kandel). Münster's work was highly influential in reviving classical geography in 16th century Europe, and providing the intellectual foundations for the production of later compilations of cartographic work, such as Ortelius' Theatrum Orbis Terrarum Münster's output includes a small format 1536 map of Europe; the 1532 Grynaeus map of the world is also attributed to him. His non-geographical output includes Dictionarium trilingue in Latin, Greek, and Hebrew, and his 1537 Hebrew Gospel of Matthew. Most of Munster's work was published by his stepson, Heinrich Petri (Henricus Petrus), and his son Sebastian Henric Petri. More by this mapmaker...