This item has been sold, but you can get on the Waitlist to be notified if another example becomes available, or purchase a digital scan.

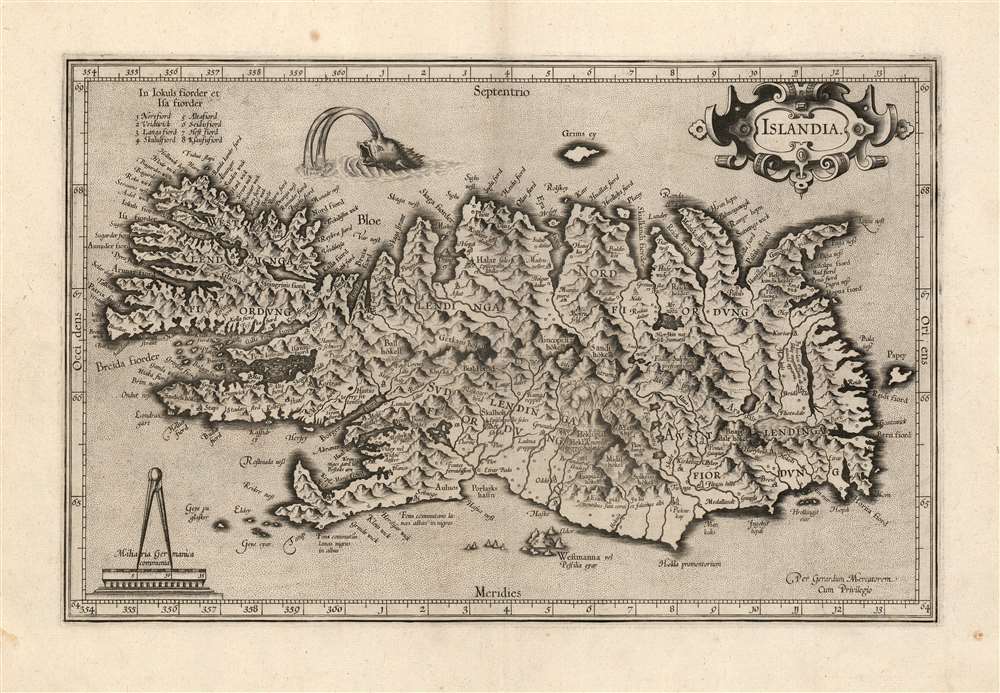

1595 Mercator Map of Iceland: Second Atlas Map of Iceland, First Edition

Iceland-mercator-1595-2

Title

1595 (undated) 11 x 17.25 in (27.94 x 43.815 cm) 1 : 2000000

Description

Sources

It is not known if Mercator received this map from Ortelius (the two were friends, so this is possible) but since the map is not a copy of the Ortelius either in detail or decor, it seems unlikely. Mercator's source may, as with Ortelius, have been Danish scholar Anders Sørensen Vedel; a third source, Henrik Rantzau, is also possible. Rantzau was both a politician and a considerable scholar, with whom Mercator is known to have corresponded in the second half of the 1580s. Their correspondence suggests that Rantzau assisted Mercator in acquiring maps from Scandinavia, and while Iceland is not referred to in these letters, it is a likely channel. Vedel and Rantzau were also acquainted, so that encourages the idea that Rantzau might have been the connection to Mercator. Regardless of the channel, it is agreed that the ultimate source of the data for both this and Ortelius' map is the same: while there are many differences between the two, the similarities are too strong to deny that both share an origin in bishop Guðbrandur's work.Variations between Mercator and Ortelius

The first and second maps of Iceland to appear in atlases do not agree in terms of latitude and longitude, suggesting that this information might not have been included in the data provided to the two mapmakers. Mercator's Iceland is somewhat further to the north than the Ortelius, and it is less wide than the earlier map: in respect to its fjords and mountains, it is less of a caricature than the Ortelius (although both maps overemphasize the island's dramatic topography.) The Mercator is in these respects simpler and more reliable than its predecessor. The map shows a good understanding of Iceland's populated centers, but uninhabited areas - the interior highlands and main glaciers, for instance - are ignored or compressed. Rivers, also, are mainly accurate but only near populated areas. It also contains more place names than Ortelius' map - although many of these do not appear to originate with bishop Guðbrandur.A Superb Engraving

This map is among the most decoratively engraved of Mercator's atlas maps; Mercator himself was an accomplished engraver, and those maps that had been completed and added to the 1595 Atlas were for the most part done by his hand. This map's stippled oceans, dramatic pictorial mountains, and neat variation between Roman and Italic lettering are hallmarks of Mercator's engraving. A sea monster - judging by the spouts, based on whale sightings - breaks the surface of the water to the north. Iceland's mount Hekla is shown erupting massively. In fact, it exploded violently in 1510 (VEI 4) and was notorious even on the mainland, thought to be a literal gate to Hell. Also named are some of the country's other famous volcanoes, such as Eyjafjallajökull (here spelled Eiapiallahokel) which erupted in 2010. The absence of the currently-erupting volcano on the Reykjanes Peninsula, Fagradalsfjall, is not a surprise: the 2021 eruption is the first of that volcano to occur in recorded history.Publication History and Census

This map was engraved at some point prior to the 1595 edition of Mercator's Atlas sive Cosmographicae, and was included in editions of the Mercator/ Hondius atlas until 1633, at which point it was replaced with an updated map. The typography of the verso text conforms to examples of the 1595 first edition of the atlas. The separate map is well represented in institutional collections, but strong examples are becoming scarce on the market.Cartographer

Gerard Mercator (March 5, 1512 - December 2, 1594) is a seminal figure in the history of cartography. Mercator was born near Antwerp as Gerard de Cremere in Rupelmonde. He studied Latin, mathematics, and religion in Rupelmonde before his Uncle, Gisbert, a priest, arranged for him to be sent to Hertogenbosch to study under the Brothers of the Common Life. There he was taught by the celebrated Dutch humanist Georgius Macropedius (Joris van Lanckvelt; April 1487 - July 1558). It was there that he changed him name, adapting the Latin term for 'Merchant', that is 'Mercator'. He went on to study at the University of Louvain. After some time, he left Louvain to travel extensively, but returned in 1534 to study mathematics under Gemma Frisius (1508 - 1555). He produced his first world map in 1538 - notable as being the first to represent North America stretching from the Arctic to the southern polar regions. This impressive work earned him the patronage of the Emperor Charles V, for whom along with Van der Heyden and Gemma Frisius, he constructed a terrestrial globe. He then produced an important 1541 globe - the first to offer rhumb lines. Despite growing fame and imperial patronage, Mercator was accused of heresy and in 1552. His accusations were partially due to his Protestant faith, and partly due to his travels, which aroused suspicion. After being released from prison with the support of the University of Louvain, he resumed his cartographic work. It was during this period that he became a close fried to English polymath John Dee (1527 - 1609), who arrived in Louvain in 1548, and with whom Mercator maintained a lifelong correspondence. In 1552, Mercator set himself up as a cartographer in Duisburg and began work on his revised edition of Ptolemy's Geographia. He also taught mathematics in Duisburg from 1559 to 1562. In 1564, he became the Court Cosmographer to Duke Wilhelm of Cleve. During this period, he began to perfect the novel projection for which he is best remembered. The 'Mercator Projection' was first used in 1569 for a massive world map on 18 sheets. On May 5, 1590 Mercator had a stroke which left him paralyzed on his left side. He slowly recovered but suffered frustration at his inability to continue making maps. By 1592, he recovered enough that he was able to work again but by that time he was losing his vision. He had a second stroke near the end of 1593, after which he briefly lost speech. He recovered some power of speech before a third stroke marked his end. Following Mercator's death his descendants, particularly his youngest son Rumold (1541 - December 31, 1599) completed many of his maps and in 1595, published his Atlas. Nonetheless, lacking their father's drive and genius, the firm but languished under heavy competition from Abraham Ortelius. It was not until Mercator's plates were purchased and republished (Mercator / Hondius) by Henricus Hondius II (1597 - 1651) and Jan Jansson (1588 - 1664) that his position as the preeminent cartographer of the age was re-established. More by this mapmaker...

Guðbrandur Þorláksson or Gudbrand Thorlakssøn (c. 1542 - July 20 1627) was bishop of Hólar, Iceland from April 1571 until his death. He was the longest-serving bishop in Iceland. He is known for printing the first complete Icelandic translation of the Bible, and for providing the data for the first accurate maps of Iceland, printed at the end of the sixteenth century by Ortelius and Mercator. He was the son of the priest Þorláks Hallgrímssonar, and Helga Jónsdóttir, daughter of the lawyer Jón Sigmundsson. He studied at Hólar College from 1553 to 1559 before studying theology and logic at the University of Copenhagen: Guðbrandur was one of the first Icelanders to study in Denmark instead of in Germany. He returned to Iceland in 1564 to serve as rector of the Skálholt School before becoming a priest. In 1571 he was named Bishop of Hólar by the Danish King Frederick II; he would serve as bishop of Hólar for 56 years.

As bishop, Guðbrandur focused on printing religious works - including hymns, and the Bible - in Icelandic. He printed nearly 100 books - many of which he wrote and translated himself. In addition to cementing the Reformation firmly in Iceland, his efforts to accurately translate these works are credited with fundamentally strengthening the Icelandic language overall.

A well-rounded scholar, Guðbrandur maintained interests in natural history, astronomy, and surveying. He is credited with the drafting of at least one new map of Iceland, upon which the first printed maps of the Island by Abraham Ortelius and Gerard Mercator were based. Learn More...