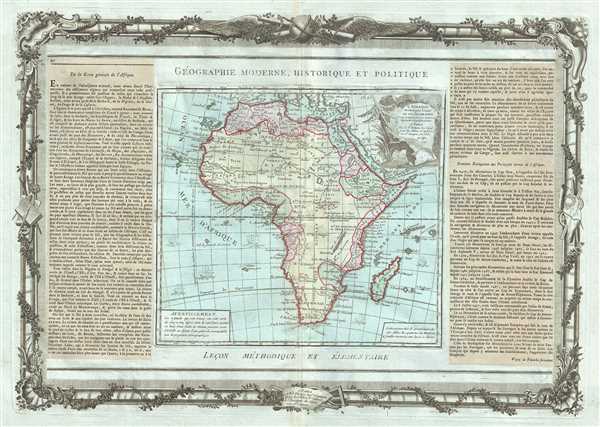

1790 Desnos Map of Africa

LAfriqueDressee-brion-1786

Title

1790 (dated) 14.5 x 21 in (36.83 x 53.34 cm) 1 : 42527000

Description

The well-mapped parts of the continent are limited to the Mediterranean Coast, Morocco, the Senegambia, the Congo, South Africa, the Kingdom of Monomatapa, Abyssinia, and Egypt. Morocco, Egypt, and the southern Mediterranean Coast (Barbary) were well known to Europeans since antiquity and the accurate mapping of these regions reflects continual contact. Further south the colonial enclaves along the Niger River (Senegal and Gambia), the Congo River, and South Africa reflect considerable detail associated with European penetration by traders and missionaries. The land of Monomopota around the Zambezi River was explored early in the 16th century by the Portuguese in hopes that the legendary gold mines supposedly found there would counterbalance the wealth flowing into Spain from the New Word. Unfortunately these mines, often associated with the Biblical kingdom of Ophir, were mostly tapped out by the 15th century. Abyssinia (modern day Ethiopia) was mapped in detail by early Italian missionaries and of considerable interest to Europeans first, because it was (and is) predominantly Christian; second, because it was a powerful well-organized and unified kingdom; and third because the sources of the Blue Nile were to be found here.

The remainder of the continent remained largely speculative though the cartographer rarely lets his imagination get the upper hand. He does however follow the well-established Ptolemaic model laid down in the Geographica regarding the sources of the White Nile – here seen as two lakes at the base of the semi-apocryphal Mountains of the Moon. However, he also presents a curious network of interconnected rivers extending westward from the confused course of the White Nile following the popular 18th century speculation that the Nile may be connected to the Niger. To his credit he does not advocate this and offers no true commerce between the two river systems.

Lake Malawi appears in a long thin embryonic state that, though it had not yet been 'discovered,' is remarkably accurate to form. Lake Malawi was not officially discovered until Portuguese trader Candido Jose da Costa Cardoso stumbled upon it in 1849 – almost one hundred years following the presentation of the lake here. The inclusion of Lake Malawi is most likely a prescient interpretation of indigenous reports brought to Europe by 17th century Portuguese traders. Its form would be followed by subsequent cartographers well into the mid-19th century when the explorations of John Hanning Speke, David Livingstone, Richard Francis Burton and others would at last yield a detailed study of Africa's interior.

A beautifully engraved title cartouche adorns the top right quadrant of the map. Sailing ships decorate the oceans. To the left and right of the map are paste downs of French text with remarks and description of the map. Surrounding the whole is an elaborate decorative border featuring floral arrangements, surveying tools, elaborate baroque scalloping, and a winged globe. This map was issued as plate no. 45 in the most deluxe edition of Desnos’ 1786 Atlas General Methodique et Elementaire, Pour l’Etude de la Geographie et de l’Histoire Moderne.

CartographerS

Louis Brion de la Tour (1743 - 1803) was the Cartographer Royal to the King of France, his official title being Ingenieur-Geographe du Roi. Despite a prolific cartographic career and several important atlases to his name, little is actually known of his life and career. He may have been born in Bordeaux. His son of the same name was born in 1763 and published until his death in 1832. It is nearly impossible to distinguish the work of the father from the work of the son, as both used the same imprint and were active in roughly the same period. Much of their work was published in partnership Louis Charles Desnos (fl. 1750 - 1790). Their most notable work is generally regarded to be his 1766 Atlas General. More by this mapmaker...

Louis Charles Desnos (1725 - April 18, 1805) was an important 18th century instrument maker, cartographer and globe maker based in Paris, France. Desnos was born in Pont-Sainte-Maxence, Oise, France, the son of a cloth merchant. From April of 1745 he apprenticed at a metal foundry. Desnos married the widow of Nicolas Hardy, sone of the map, globe, and instrument seller Jacques Hardy. Desnos held the coveted position of Royal Globemaker to the King of Denmark, Christian VII, for which he received a stipend of 500 Livres annually. In return Desnos sent the King roughly 200 Livres worth of maps, books and atlases each year. As a publisher, Desnos produced a substantial corpus of work and is often associated with Zannoni and Louis Brion de la Tour (1756-1823). Despite or perhaps because of the sheer quantity of maps Desnos published he acquired a poor reputation among serious cartographic experts, who considered him undiscerning and unscrupulous regarding what he would and would not publish. Desnos consequently had a long history of legal battles with other Parisian cartographers and publishers of the period. It is said that he published everything set before him without regard to accuracy, veracity, or copyright law. Desnos maintained offices on Rue St. Jacques, Paris. Learn More...