This item has been sold, but you can get on the Waitlist to be notified if another example becomes available, or purchase a digital scan.

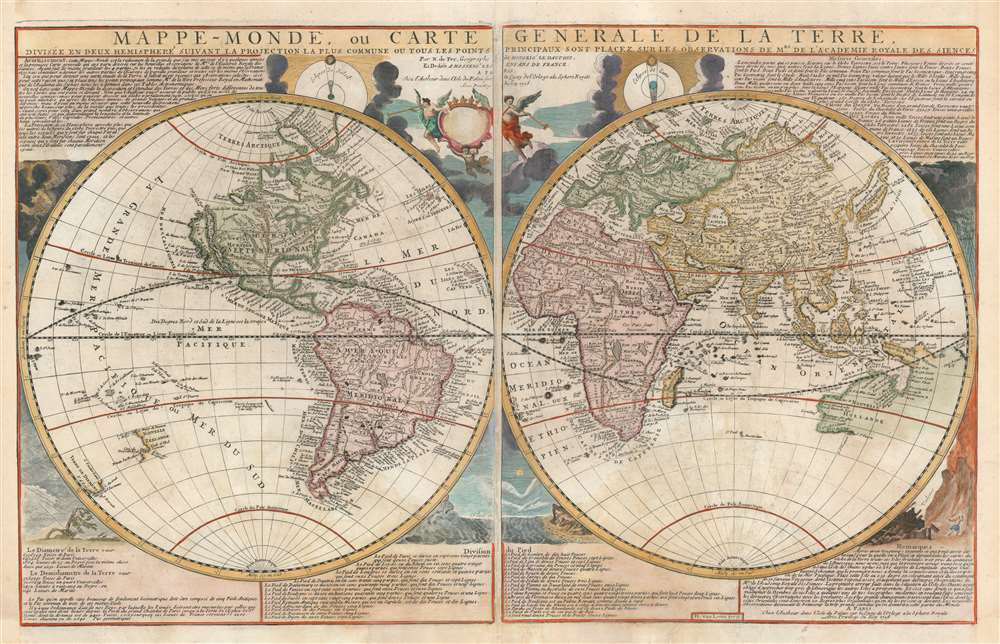

1717 De Fer Map of the World in Hemispheres

MappeMonde-defer-1718

Title

1718 (dated) 18.5 x 30 in (46.99 x 76.2 cm) 1 : 58000000

Description

A Survey of the Cartography

The map features much of interest and our survey of the document will begin with North America, where California is presented in insular form on the Luke Foxe model - this is discussed in detail below. North of California, the Pacific northwest is blank - underscoring the limited knowledge of this region then available. In the eastern part of North America, two large speculative lakes appear near Carolina / Georgia. These represent Lacus Aquae Dulche or Lake Apalache, discussed in detail below.South America follows conventional mappings of the period wherein the coasts are well delineated but the interior, especially in modern day Brazil and Guyana, is largely speculative. Two lakes of note appear. Centrally, a large unnamed lake appears as the source of the Paraguay River, this is the legendary Laguna de Xarayes (discussed in detail below), believed to be the Gateway to El Dorado. El Dorado, the city of gold, is more commonly associated with another mythical lake in Guiana. This lake, generally known as Parima, appears here in Cassipa, and was first associated with El Dorado by Sir Francis Raleigh in the 16th century. Here much reduced, Parima / Cassipa represents the very real Lake Amucu, which rests on a large flood plain that occasionally fills, giving the impression of an inland sea.

Africa is tenuously mapped and, save for the coastline, is almost entirely speculative. The course of the Blue Nile correctly terminates in Lake Tana (Ethiopia), but the White Nile is directed to a apocryhal trans-continental mountain range - one of several that erroneously crisscross the Sahara and which would later be known as the Mountains of Kong. Further south ,the Ptolemaic lakes, Zaire and Zembre - traditionally the sources of the White Nile. float independent of other geographical features in an enormous Paid Inconnus.

Asia is mapped according to a combination of actual exploration, indigenous knowledge, and reports that date back to the travels of Marco Polo and the literature of antiquity. The Caspian Sea is malformed - as was common until the 1719 - 1721 surveys of Karl van Verden. Southeast Asia, long trafficked by European merchants, is well mapped. East Asia is more tenuously mapped further north. Japan approximates its actual form, with Yeso (Hokkaido) remarkably separate, but the coast to the east of Korea extends off the map to the northeast - and fails to reappear on the other side! The apocryphal Lake Chiamay, speculative source of the 5 great rivers of Southeast Asia, is mapped in what would today be Yunnan, China.

Australia, New Zealand, Tasmania, and New Guinea are mapped extremely tenuously. Only the western and northern coasts of Australia are mapped and these are merged with New Guinea. A variation in color coding suggests that the mapmaker may believe these to be separate, but the question is left intentionally ambiguous. Only southern Tasmania and parts of Eastern New Zealand are mapped, referencing 17th century Dutch exploration. Other islands in the Pacific are even more speculative. Davis Island, discovered by the English in 1685, is most likely Easter Island. Other islands, some roughly in the vicinity of Hawaii, are purely speculative and not representative of actual discovery.

Insular California

The idea of an insular California first appeared as a work of fiction in Garci Rodriguez de Montalvo's c. 1510 romance Las Sergas de Esplandian, where he writesKnow, that on the right hand of the Indies there is an island called California very close to the side of the Terrestrial Paradise; and it is peopled by black women, without any man among them, for they live in the manner of Amazons.Baja California was subsequently discovered in 1533 by Fortun Ximenez, who had been sent to the area by Hernan Cortez. When Cortez himself traveled to Baja, he must have had Montalvo's novel in mind, for he immediately claimed the 'Island of California' for the Spanish King. By the late 16th and early 17th century ample evidence had been amassed, through explorations of the region by Francisco de Ulloa, Hernando de Alarcon, and others, that California was in fact a peninsula. Nonetheless, by this time other factors were in play. Francis Drake had sailed north and claimed Nova Albion, modern day Washington or Vancouver, for England. The Spanish thus needed to promote Cortez's claim on the 'Island of California' to preempt English claims on the western coast of North America. The significant influence of the Spanish crown on European cartographers spurred a major resurgence of the Insular California theory.

Insular California: Luke Foxe / Sanson Model

The present map illustrates the island of California on the famous Luke Foxe / Sanson model. The insular California presented here is often erroneously referred to as the 'Sanson Model.' The term is in fact derived from a 1635 map of the North American Arctic drown by Luke Foxe. It was Foxe who invented many of the place names as well as added various bays and inlets to northern California. Among these are Talaaago, R. de Estiete, and the curious peninsula extending westward form the mainland, Agubela de Cato. Foxe's sources remain a mystery and his mapping may be based upon nothing more than fantasy, but Sanson embraced the model whole heartedly. Although Sanson did not invent this form of insular California, his substantial influence did popularize it with subsequent cartographers.Great Freshwater Lake of the Southeast

In Spanish Florida, which extends north to include most of the American Southeast, Lake Apalache, often called Lacus Aquae Dulce or the 'Freshwater Lake of the American Southeast' is noted. This lake, first mapped by De Bry and Le Moyne in the mid-16th century, is a mis-mapping of Florida's Lake George. While Theodor De Bry, working in 1565, correctly mapped the lake as part of the River May or St. John's River, subsequent navigators and cartographers in Europe erroneously associated it with the Savannah River, which instead of Flowing south from the Atlantic (Like the May), flowed almost directly from the Northwest. This error was taken up by Hondius and Mercator who, in their 1606 map, invert the course of the May River thus situating this lake far to the northwest in Appalachia. Consequently, 'through mutations of location and size [this] became the great inland lake of the Southeast' (Cumming, 478) – an apocryphal cartographic element that would remain one of Le Moyne's most tenacious legacies. Lake Apalache was subsequently relocated somewhere in Carolina or Georgia, where De Fer maps it and where it would remain for several hundred years.Laguna de Xarayes

The mythical Laguna de Xarayes is illustrated here as the northern terminus, or source, of the Paraguay River. The Xarayes, a corruption of 'Xaraies' meaning 'Masters of the River', were an indigenous people occupying what are today parts of Brazil's Matte Grosso and the Pantanal. When Spanish and Portuguese explorers first navigated up the Paraguay River, as always in search of El Dorado, they encountered the vast Pantanal flood plain at the height of its annual inundation. Understandably misinterpreting the flood plain as a gigantic inland sea, they named it after the local inhabitants, the Xaraies. The Laguna de los Xarayes almost immediately began to appear on early maps of the region and, at the same time, to take on a legendary quality. Later missionaries and chroniclers, particularly Díaz de Guzman, imagined an island in this lake and curiously identified it as an 'Island of Paradise,'...an island [of the Paraguay River] more than ten leagues [56 km] long, two or three [11-16 km] wide. A very mild land rich in a thousand types of wild fruit, among them grapes, pears and olives: the Indians created plantations throughout, and throughout the year sow and reap with no difference in winter or summer, ... the Indians of that island are of good will and are friends to the Spaniards; Orejón they call them, and they have their ears pierced with wheels of wood ... which occupy the entire hole. They live in round houses, not as a village, but each apart though keep up with each other in much peace and friendship. They called of old this island Land of Paradise for its abundance and wonderful qualities.Here, although unlabeled, the Laguna is exceptionally large and inviting.

Publication History and Census

This map was first published in 1700 by Nicolas de Fer, who ordered it engraved by Herman van Loon. The map is primary derived from his 1694 wall map, but his heavily updated through, especially in California, Australia, and Japan. The map is known in 6 editions, all of which vary slightly with regard to the dates, imprint, and dedication, but are otherwise cartographically similar. These were 1700, 1702, 1705, 1708, 1718, and 1728. The present example, with its blank cartouche and simple crown, appears to be an intermediary proof state, somewhere between 1708 and 1718. Although this map appears on the market from time to time in its various editions, the present mid-state proof is unique.CartographerS

Nicholas de Fer (1646 - October 25, 1720) was a French cartographer and publisher, the son of cartographer Antoine de Fer. He apprenticed with the Paris engraver Louis Spirinx, producing his first map, of the Canal du Midi, at 23. When his father died in June of 1673 he took over the family engraving business and established himself on Quai de L'Horloge, Paris, as an engraver, cartographer, and map publisher. De Fer was a prolific cartographer with over 600 maps and atlases to his credit. De Fer's work, though replete with geographical errors, earned a large following because of its considerable decorative appeal. In the late 17th century, De Fer's fame culminated in his appointment as Geographe de le Dauphin, a position that offered him unprecedented access to the most up to date cartographic information. This was a partner position to another simultaneously held by the more scientific geographer Guillaume De L'Isle, Premier Geograph de Roi. Despite very different cartographic approaches, De L'Isle and De Fer seem to have stepped carefully around one another and were rarely publicly at odds. Upon his death of old age in 1720, Nicolas was succeeded by two of his sons-in-law, who also happened to be brothers, Guillaume Danet (who had married his daughter Marguerite-Geneviève De Fer), and Jacques-François Bénard (Besnard) Danet (husband of Marie-Anne De Fer), and their heirs, who continued to publish under the De Fer imprint until about 1760. It is of note that part of the De Fer legacy also passed to the engraver Remi Rircher, who married De Fer's third daughter, but Richer had little interest in the business and sold his share to the Danet brothers in 1721. More by this mapmaker...

Harmanus van Loon (fl. c. 1690 - c. 1725) was a Flemish engraver active in Paris during the late 17th and early 18th centuries. Van Loon worked primarily in Paris and often signed his work, which includes maps and other engravings for such prominent cartographers as Nicolas de Fer, Jean Baptiste Nolin, Guillaume Delisle, and others. There is some speculation that he may have been related to the Brussels born painter Theodorus van Loon. Learn More...