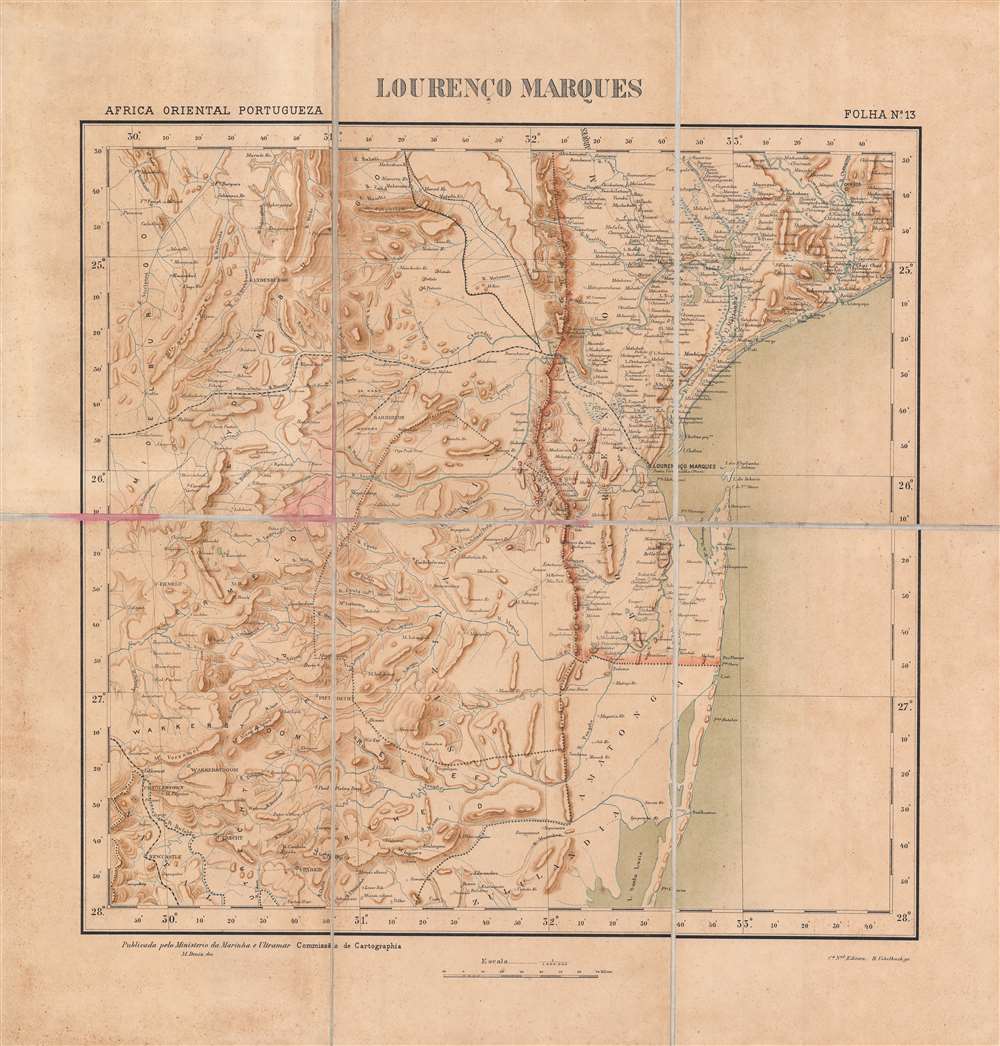

1896 Comissão Map of Maputo (Lourenço Marques), Mozambique, and Environs

Maputo-comissaocartographia-1896$800.00

Title

Lourenço Marques.

1896 (undated) 16.75 x 17.25 in (42.545 x 43.815 cm) 1 : 1000000

1896 (undated) 16.75 x 17.25 in (42.545 x 43.815 cm) 1 : 1000000

Description

This is a rare c. 1896 folding map of Lourenço Marques (now Maputo) and its surrounding region in Portuguese East Africa (Mozambique) made by the Comissão de Cartografia das Colónias. The map was produced in the wake of a Portuguese-British struggle for primacy in southeastern Africa and attempts by the South African Republic to maintain its independence by using Lourenço Marques as an outlet to the coast.

The history of Lourenço Marques is closely tied to the southernmost of the two railways shown here extending into the Transvaal, eventually to Pretoria, known to the Portuguese as the Ressano Garcia Railway and to the Boers and British as the Delagoa Bay Railway or the NZAM / NSAM line, after the company that built it, the Netherlands–South African Railway Company (Nederlands-Suid-Afrikaanse Spoorwegmaatskappy). The northern of the two lines was a proposed line to Leydsdorp and towards Pietersburg (Polokwane) that was abandoned when Leydsdorp, a gold rush town, virtually disappeared with the shifting of gold mining to the Witwatersrand in the late 1880s.

The area gained renewed significance with the development of the neighboring Transvaal (South African Republic) starting in the 1850s. As British designs on the Transvaal increased, eventually causing the First Boer War (1880 – 1881), it was a matter of dispute between the British and Portuguese as to who should control the area around Lourenço Marques. The Royal Navy occupied Inhaca Island in Delagoa Bay from 1861 to 1875 and claimed it as British territory, a claim only relinquished by the diplomatic intervention of the French. The incident was resolved on favorable terms for Portugal, but presaged later battles with the British over lands further to the north (discussed below), which ended on terms much more favorable to Britain.

Especially once extensive gold deposits were discovered in the Transvaal in 1886, adjoining areas including Lourenço Marques became increasingly important. The Portuguese, already anxious about the status of their control over Mozambique, invested heavily in the city to develop it into a major port, with considerable success. The completion of the Ressano Garcia Railway in 1895 also greatly aided the city's development, to the point that Lourenço Marques was made the capital of Mozambique in 1898.

With well-equipped port facilities linking to railways that brought raw materials from the interior, the city grew considerably in the early 20th century and attracted capital and migrants from distant shores. In the years before independence in 1975, it had also developed a lively service economy around tourism and related amenities. Although the civil war from 1977 to 1992 was devastating to the city, it has rebounded in the years since a peace settlement ended the war and remains Mozambique's largest and wealthiest city.

In the early 20th century, two additional lines were built from Lourenço Marques, one to Swaziland (the Goba Railway) and one along the Limpopo River into eastern Rhodesia (Zimbabwe) (the Limpopo Railway). These railways had a clear economic logic as they primarily served mining interests, but it was still difficult to finance and construct the projects given the mountainous and flood-prone terrain between the coast and the interior.

In the late 1870s and 1880s, the Portuguese tried to establish an East-West corridor across central Africa, a plan laid out in the famous 1885 Mapa cor-de-rosa (Pink Map). This project was motivated by the doctrine of effective occupation agreed to at the Berlin Conference of 1884 – 1885, where the Portuguese also gained the support of other European powers for their plan, except for Britain, whose subjects were advancing into these same areas and who imagined a string of colonies running north and south 'from the Cape to Cairo' that would intersect with Portugal's claims.

In the wake of the Berlin Conference, rival colonial powers raced to establish 'effective occupation' and claim territory. Portuguese troops under Alexandre de Serpa Pinto attempted several times to make inroads with local chiefs in the Shire Highlands around Blantyre and establish a protectorate. In September 1889, Serpa Pinto crossed the Ruo River at Chiromo (here as Chilomo), a move that led the British in Blantyre to declare a Shire Highland Protectorate to fend off the Portuguese advances. The situation came to a head when Serpa Pinto's troops fought with troops of Kokolo chiefs aligned with the British and moved towards Blantyre itself.

In January 1890, the British sent an ultimatum that the Portuguese relinquish their claims laid out on the Pink Map and sign a treaty fixing the borders on terms favorable to the British. The much weaker Portuguese were forced to accept Britain's will and watch helplessly as British interests expanded into the lands they had recently claimed. The subsequent Anglo-Portuguese Treaty of 1891 confirmed British primacy in the region and established territorial divisions that still predominate in central and eastern Africa. The incident was an embarrassment for the young King Carlos I and for the entire nation, and was used as an opportunity by republican revolutionaries to stage a (failed) revolt in Porto. The monarchy's reputation never recovered from the episode; Carlos was assassinated along with his designated heir in 1908 and the monarchy was overthrown and abolished in 1910.

In the early-mid 19th century, the government launched a renewed effort to move colonists further inland and strengthen direct control over the interior. The 'Scramble for Africa' at the end of the century presented Portugal both risks and opportunities. But, as discussed above, they were incapable of challenging the British and had to grudgingly accept a secondary role among European colonial powers there. Despite their earlier antagonism, the British and Portuguese were both wary of German expansion in Africa in the late 19th century and collaborated against Germany during the First World War. Although Portugal was neutral at the start of the conflict, it supplied the British and French armies on the Western Front and was eventually drawn into the war on the Allied side in 1916, focusing mainly on protecting its African colonies.

In the interwar period, with the threat of anti-colonial movements looming, Portugal moved towards a notion of 'pluricontinental' nationhood. Nevertheless, with the wave of decolonization that followed World War II, Portugal faced the prospect of losing its colonies, but the country's Prime Minister and de facto dictator, António de Oliveira Salazar, categorically refused decolonization and aimed to crush guerilla movements in Angola, Mozambique, and Portuguese Guinea (now Guinea-Bissau). Counter-insurgency efforts were largely successful as a short-term solution, but failed to resolve underlying problems, and when Salazar's successor Marcelo Caetano was toppled in a coup in 1974, Portugal's empire quickly collapsed. Angola and Mozambique then descended into protracted civil wars that became Cold War proxy conflicts that were only resolved years later.

A Closer Look

This map shows the southernmost portion of Portuguese East Africa (Africa Oriental Portugueza), or Mozambique (Moçambique). The red-shaded line to the west and south of Lourenço Marques is the border between Mozambique and nearby territories, including the Transvaal and various indigenous kingdoms, namely Swaziland (Eswatini) and Tongaland (Maputaland).The history of Lourenço Marques is closely tied to the southernmost of the two railways shown here extending into the Transvaal, eventually to Pretoria, known to the Portuguese as the Ressano Garcia Railway and to the Boers and British as the Delagoa Bay Railway or the NZAM / NSAM line, after the company that built it, the Netherlands–South African Railway Company (Nederlands-Suid-Afrikaanse Spoorwegmaatskappy). The northern of the two lines was a proposed line to Leydsdorp and towards Pietersburg (Polokwane) that was abandoned when Leydsdorp, a gold rush town, virtually disappeared with the shifting of gold mining to the Witwatersrand in the late 1880s.

Lourenço Marques – from Sleepy Colonial Outpost to Megaport

Although the area that is now home to Maputo had been explored by the Portuguese, led by navigator Lourenço Marques, in the mid-16th century, the current city only began to grow in the mid-19th century and there were in fact multiple trading post-garrisons named Lourenço Marques around Delagoa Bay (Maputo Bay). The present city only dates to around 1850, when Portuguese settlers built a small town around a Portuguese fort that had been abandoned some 65 years before.The area gained renewed significance with the development of the neighboring Transvaal (South African Republic) starting in the 1850s. As British designs on the Transvaal increased, eventually causing the First Boer War (1880 – 1881), it was a matter of dispute between the British and Portuguese as to who should control the area around Lourenço Marques. The Royal Navy occupied Inhaca Island in Delagoa Bay from 1861 to 1875 and claimed it as British territory, a claim only relinquished by the diplomatic intervention of the French. The incident was resolved on favorable terms for Portugal, but presaged later battles with the British over lands further to the north (discussed below), which ended on terms much more favorable to Britain.

Especially once extensive gold deposits were discovered in the Transvaal in 1886, adjoining areas including Lourenço Marques became increasingly important. The Portuguese, already anxious about the status of their control over Mozambique, invested heavily in the city to develop it into a major port, with considerable success. The completion of the Ressano Garcia Railway in 1895 also greatly aided the city's development, to the point that Lourenço Marques was made the capital of Mozambique in 1898.

With well-equipped port facilities linking to railways that brought raw materials from the interior, the city grew considerably in the early 20th century and attracted capital and migrants from distant shores. In the years before independence in 1975, it had also developed a lively service economy around tourism and related amenities. Although the civil war from 1977 to 1992 was devastating to the city, it has rebounded in the years since a peace settlement ended the war and remains Mozambique's largest and wealthiest city.

Railways and Inter-imperial Relations

The rail infrastructure of southeastern Africa was bound up in a competition between British and Portuguese colonial interests, as well as efforts by the South African Republic to maintain its independence in the face of British encroachment. The landlocked S.A.R., having already staved off the British in the First Boer War, was eager for outlets to the coast that did not run through British territory, especially after the Witwatersrand Gold Rush began in 1886. The Ressano Garcia Railway, which had been discussed since 1874, was a personal ambition of Paul Kruger, President of the S.A.R. from 1883 to 1900, who saw the railway as essential to the survival of the republic. Although this ambition was unrealized as a result of the Second Boer War (1899 – 1902) and the incorporation of the Boer Republics into the British Empire as colonies, the railway continued to serve as an important conduit for the region.In the early 20th century, two additional lines were built from Lourenço Marques, one to Swaziland (the Goba Railway) and one along the Limpopo River into eastern Rhodesia (Zimbabwe) (the Limpopo Railway). These railways had a clear economic logic as they primarily served mining interests, but it was still difficult to finance and construct the projects given the mountainous and flood-prone terrain between the coast and the interior.

The Anglo-Portuguese Crisis

In the years before this map was made, the British and Portuguese were tussling for influence in southeastern Africa. Since the 1830s, the Portuguese had attempted to expand their control over Mozambique, which was only nominal inland from the coast, by offering large estates (prazo) to colonists and shoring up ties with local rulers who were their supposed vassals, or in other cases sponsoring rival factions to gain the upper hand in various localities. At the same time, British missionaries and mining interests led by Cecil Rhodes and his British South Africa Company were moving into lands to the west of Mozambique, signing agreements with local chiefs, obtaining mining rights and establishing protectorates over their lands.In the late 1870s and 1880s, the Portuguese tried to establish an East-West corridor across central Africa, a plan laid out in the famous 1885 Mapa cor-de-rosa (Pink Map). This project was motivated by the doctrine of effective occupation agreed to at the Berlin Conference of 1884 – 1885, where the Portuguese also gained the support of other European powers for their plan, except for Britain, whose subjects were advancing into these same areas and who imagined a string of colonies running north and south 'from the Cape to Cairo' that would intersect with Portugal's claims.

In the wake of the Berlin Conference, rival colonial powers raced to establish 'effective occupation' and claim territory. Portuguese troops under Alexandre de Serpa Pinto attempted several times to make inroads with local chiefs in the Shire Highlands around Blantyre and establish a protectorate. In September 1889, Serpa Pinto crossed the Ruo River at Chiromo (here as Chilomo), a move that led the British in Blantyre to declare a Shire Highland Protectorate to fend off the Portuguese advances. The situation came to a head when Serpa Pinto's troops fought with troops of Kokolo chiefs aligned with the British and moved towards Blantyre itself.

In January 1890, the British sent an ultimatum that the Portuguese relinquish their claims laid out on the Pink Map and sign a treaty fixing the borders on terms favorable to the British. The much weaker Portuguese were forced to accept Britain's will and watch helplessly as British interests expanded into the lands they had recently claimed. The subsequent Anglo-Portuguese Treaty of 1891 confirmed British primacy in the region and established territorial divisions that still predominate in central and eastern Africa. The incident was an embarrassment for the young King Carlos I and for the entire nation, and was used as an opportunity by republican revolutionaries to stage a (failed) revolt in Porto. The monarchy's reputation never recovered from the episode; Carlos was assassinated along with his designated heir in 1908 and the monarchy was overthrown and abolished in 1910.

Portugal's 'Third Empire'

In the early 19th century, Portugal was no longer a great world power, and its empire was significantly reduced, especially after the independence of Brazil in 1822. But the empire did still maintain a string of colonies, the largest of which were Angola and Mozambique. Some Portuguese had ventured into the African interior in the early days of their colonial presence and set up estates and trading post-garrisons. However, settlers were few in number and generally intermarried with the local population to the point that they lost Portuguese identity, while the estates were operated like independent fiefdoms rather than a shared colonial enterprise. The Portuguese inclination to try to force Christianity on their trading partners and use the presence of Muslim traders as an excuse for military campaigns also provoked opposition. Therefore, Portugal's control was mostly limited to coastal ports and most of the people it claimed to rule were effectively independent.In the early-mid 19th century, the government launched a renewed effort to move colonists further inland and strengthen direct control over the interior. The 'Scramble for Africa' at the end of the century presented Portugal both risks and opportunities. But, as discussed above, they were incapable of challenging the British and had to grudgingly accept a secondary role among European colonial powers there. Despite their earlier antagonism, the British and Portuguese were both wary of German expansion in Africa in the late 19th century and collaborated against Germany during the First World War. Although Portugal was neutral at the start of the conflict, it supplied the British and French armies on the Western Front and was eventually drawn into the war on the Allied side in 1916, focusing mainly on protecting its African colonies.

In the interwar period, with the threat of anti-colonial movements looming, Portugal moved towards a notion of 'pluricontinental' nationhood. Nevertheless, with the wave of decolonization that followed World War II, Portugal faced the prospect of losing its colonies, but the country's Prime Minister and de facto dictator, António de Oliveira Salazar, categorically refused decolonization and aimed to crush guerilla movements in Angola, Mozambique, and Portuguese Guinea (now Guinea-Bissau). Counter-insurgency efforts were largely successful as a short-term solution, but failed to resolve underlying problems, and when Salazar's successor Marcelo Caetano was toppled in a coup in 1974, Portugal's empire quickly collapsed. Angola and Mozambique then descended into protracted civil wars that became Cold War proxy conflicts that were only resolved years later.

Publication History and Census

This map was prepared by M. Diniz of the Comissão de Cartografia das Colónias, an office within the Portuguese Ministério da Marinha e Ultramar, and published in 1896 by R. Uebelhack. It was Sheet No. 13 in the in the collection Africa Oriental Portugueza (OCLC 945552666). The map is not cataloged individually in the holdings of any institution, and the collection just mentioned is only held by Yale University, the Library of Congress, and the Bibliotheek Universiteit van Amsterdam. This map has no known history on the market.Cartographer

Comissão de Cartografia das Colónias (fl. c. 1883 - 1936), in its early years as 'Comissão de Cartographia das Colónias', was an office within the Ministério da Marinha e Ultramar tasked with surveying Portugal's colonies, primarily in Africa. It was dissolved in 1936 and replaced with Junta das Missões Geográficas e de Investigações Colonia. More by this mapmaker...

Condition

Good. Some staining along the fold lines and in the margins.