This item has been sold, but you can get on the Waitlist to be notified if another example becomes available.

1851 Espy Meteorological Maps / Atlas of the United States

MeteorologyReports-espy-1851

Title

1851 (dated) 11 x 15 in (27.94 x 38.1 cm)

Description

A Closer Look

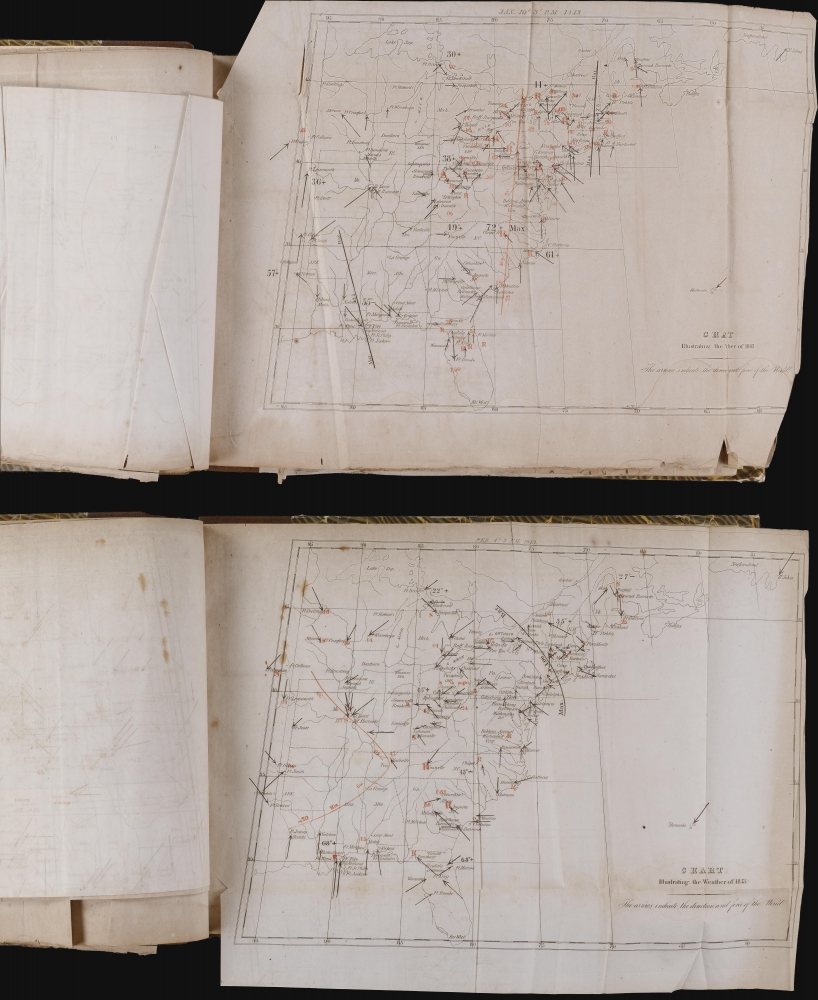

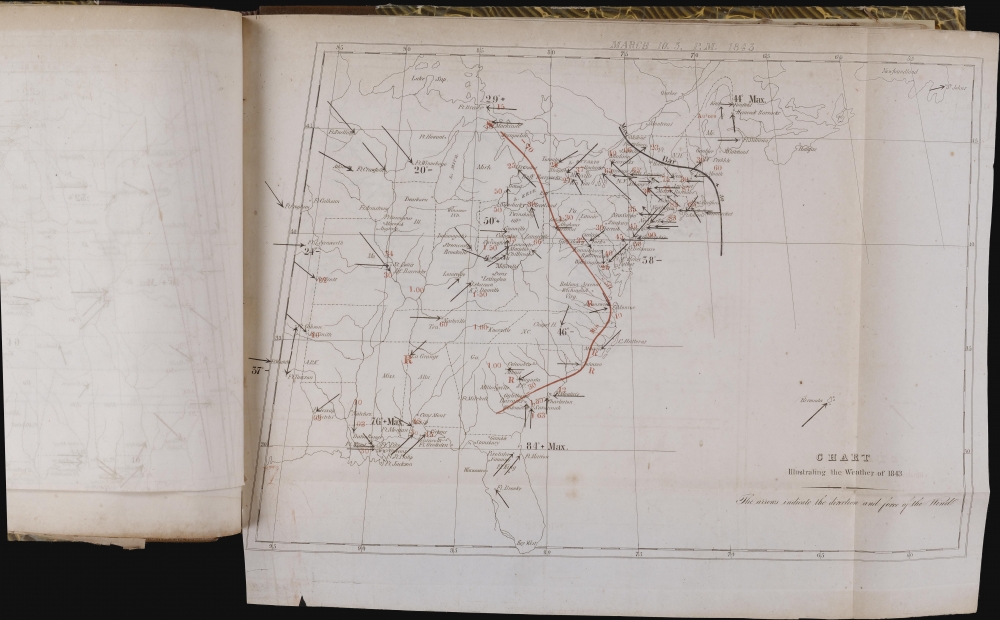

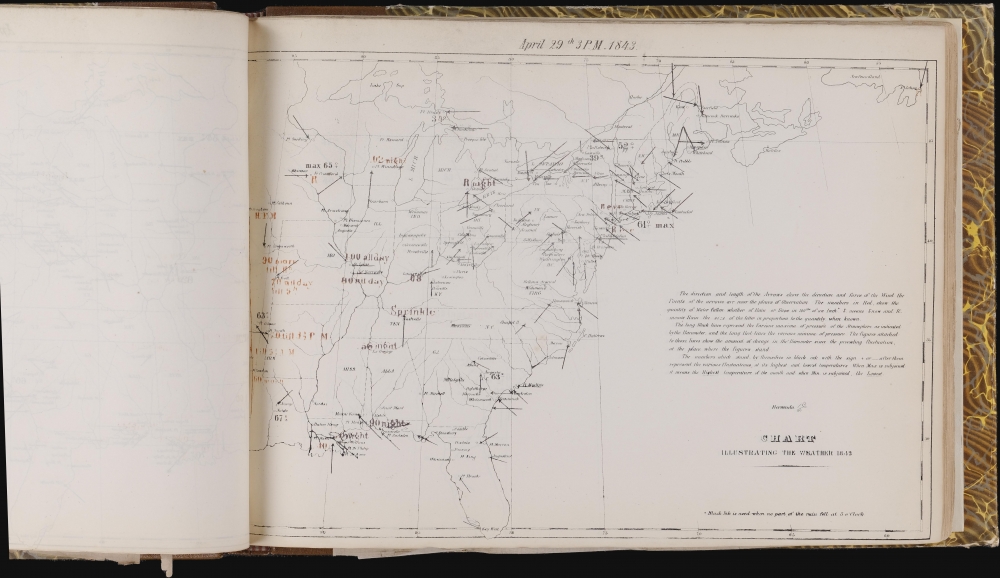

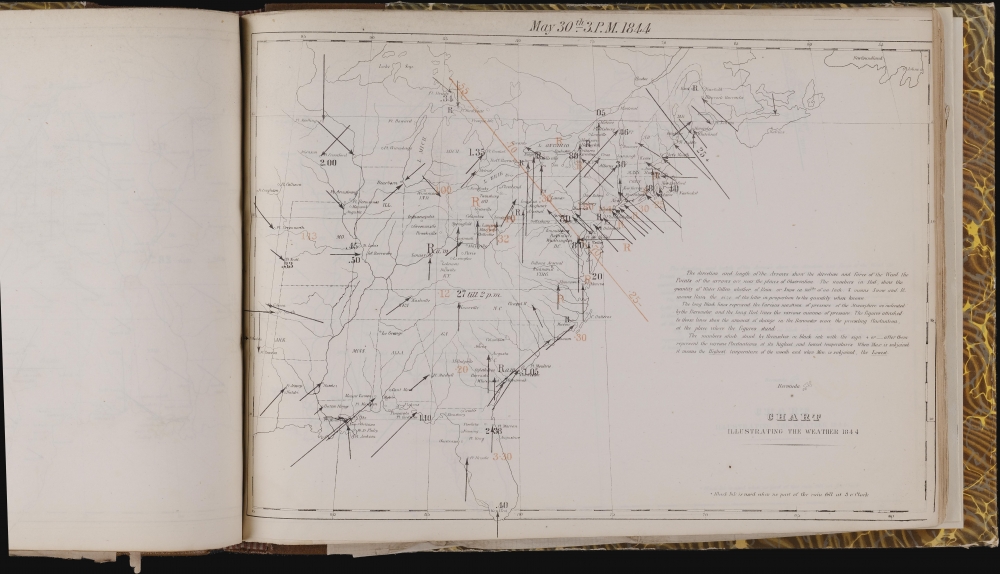

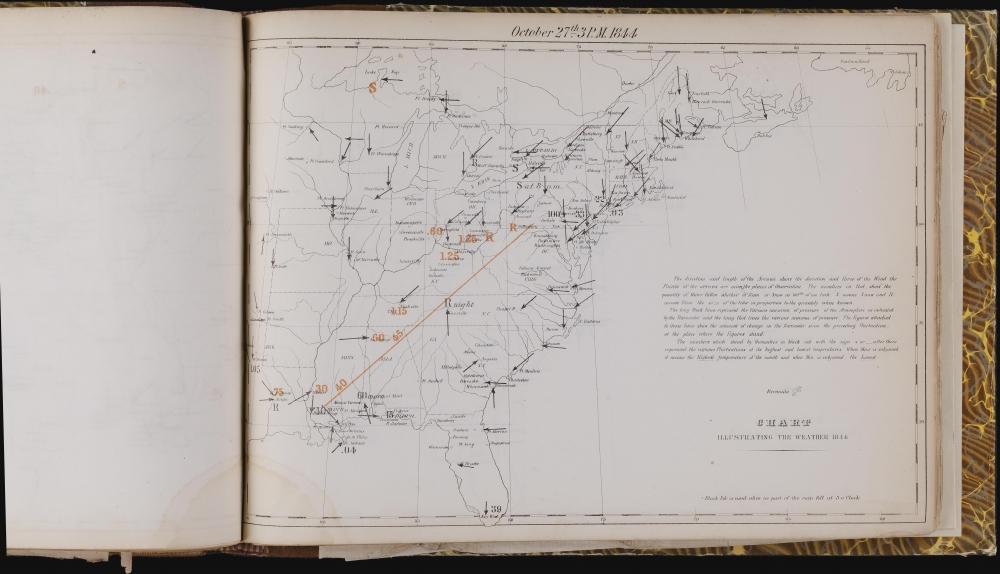

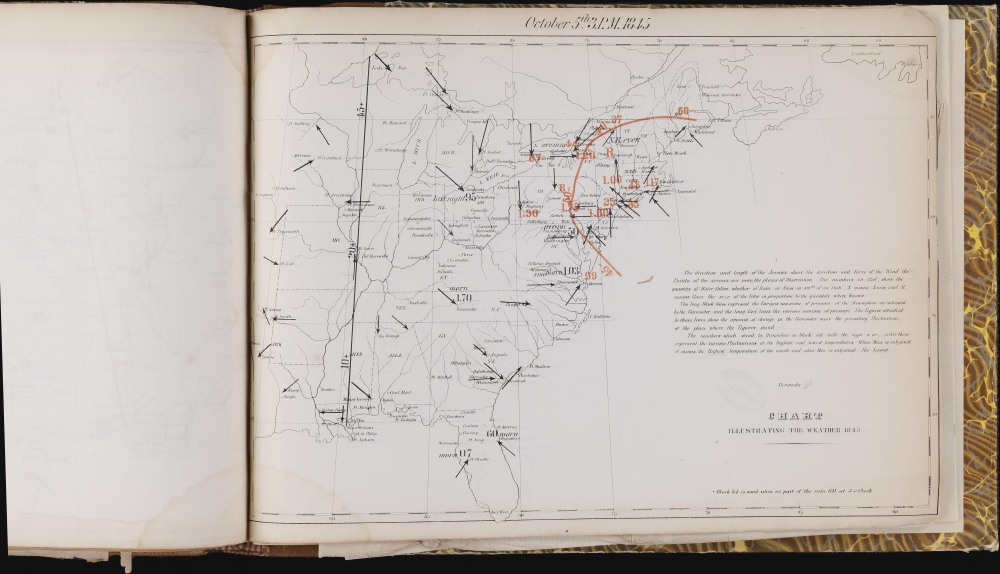

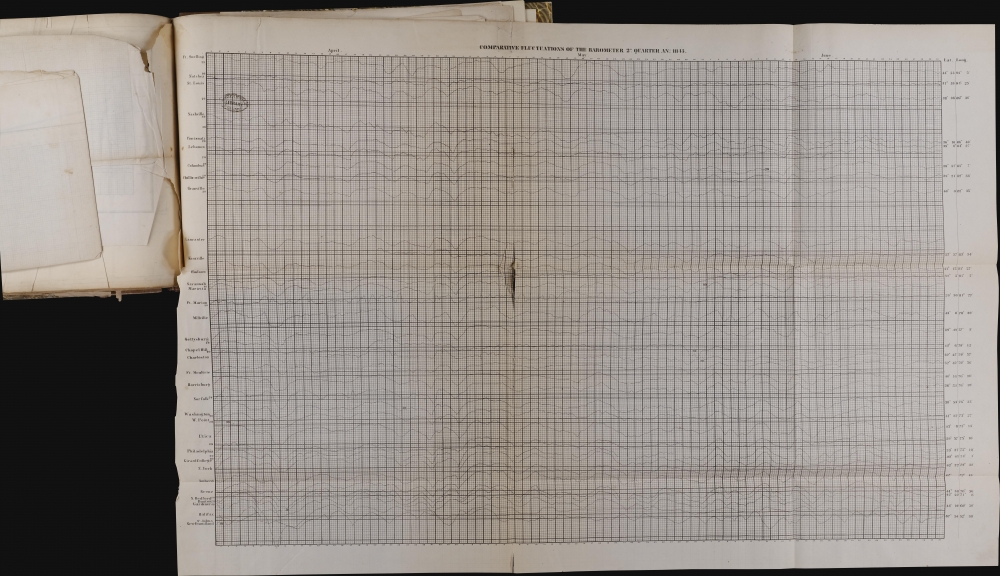

The single bound volume contains the full contents of the first three Espy meteorological reports, featuring some 130 maps and related texts. 29 weather maps were published with the 1st report, and another 101 with the 2nd and 3rd reports. 10 large fold-out comparative barometric charts are included at the end volume. Each chart compares barometric readings from across the eastern United States over a period of three months.Espy Explains the Maps

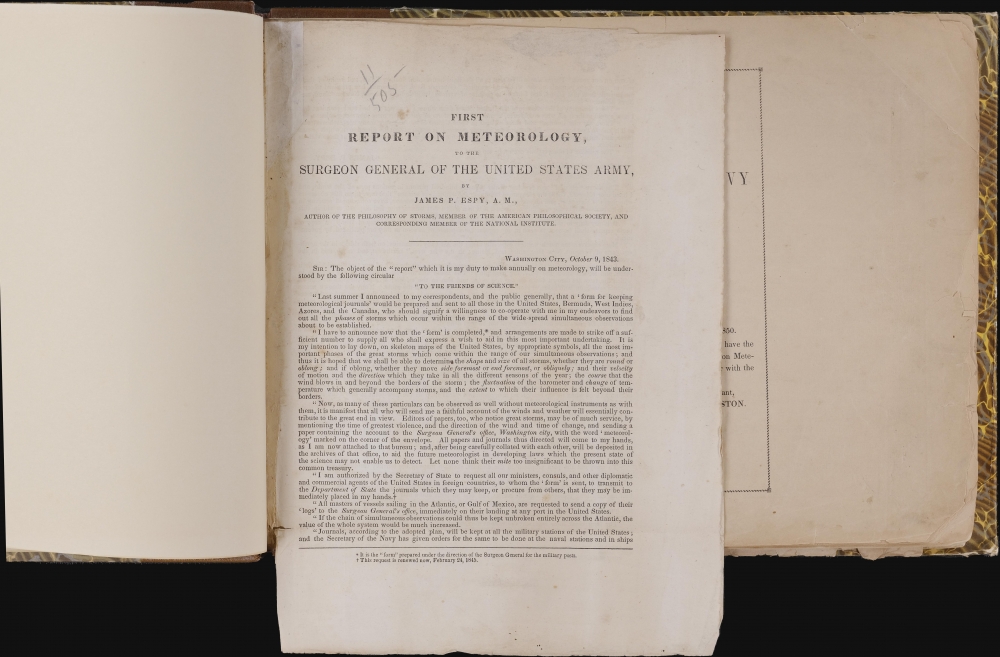

In the short 4-page text that accompanied the first report, Espy explains the cartographic symbols and notations. These are as followsTo carry out the plan proposed in the circular, skeleton maps of the territory embracing the observations were procured; and on these maps were laid down the observations taken by the various observers at three o'clock, p.m., of each day, unless another hour is specifically mentioned.

The direction of the arrows shows the direction of the wind, and the length shows its force. An arrow half an inch long represents a gentle breeze, and one an inch and a half a very violent wind; and so in proportion. The points of the arrows are near the places of observation. The numbers in red ink represent the quantity of water fallen, whether in rain or snow, in hundredths of an inch. S means snow, and R means rain. A large S means a great snow, and a small s means a little snow; and so for rain.

The long black lines represent the various maxima of pressure of the atmosphere, as indicated by the barometer; and the long red lines represent the various minima of pressure. The figures attached to these lines represent the amount of change in the barometer since the preceding fluctuation at the place where the figures stand.

The numbers which stand by themselves in black ink, with the sign + or - after them, represent the various fluctuations of the thermometer at its highest and lowest temperatures.

Espy's Goals

In the text of the First Report, Espy explains his vision of a national (and international) network of weather observers with the goal of documenting and understanding storm systems. He included most of this text in a letter sent to potential collaborators on December 6, 1842.Last summer I announced to my correspondents, and the public generally, that a 'form for keeping meteorological journals' would be prepared and sent to all those in the United States, Bermuda, West Indies, Azores, and the Canadas, who should signify a willingness to co-operate with me in my endeavors to find out all the phases of storms which occur within the range of the wide-spread simultaneous observations about to be established.This plan ultimately proved successful. He created a network of 50 observers who noted barometric pressure along with other weather information at their location, along with another 60 who did not have a barometer but recorded the other information. Unfortunately for Espy, a nationwide telegraph network did not yet exist making in-the-moment storm prediction impossible.

I have to announce now that the 'form' is completed, and arrangements are made to strike off a sufficient number to supply all who shall express a wish to aid in this most important undertaking. It is my intention to lay down, on skeleton maps of the United States, by appropriate symbols, all the most important phases of the great storms which come within the range of our simultaneous observations; and thus it is hoped that we shall be able to determine the shape and size of all storms, whether they are round or oblong; and if oblong, whether they move side foremost or end foremost, or obliquely; and their velocity of motion and the direction which they take in all the different seasons of the year; the course that the wind blows in and beyond the borders of the storm; the fluctuation of the barometer and change of temperature which generally accompany storms, and the extent to which their influence is felt beyond their borders.'

A Short History of Early Meteorology in the United States

Unofficial weather records exist from as early as 1644 - 1645, when Reverend John Campanus recorded the weather at the Swedes' Fort near Wilmington, Delaware. 84 years later, Paul Dudley, Chief Justice of Massachusetts, compiled the next round of unofficial records. Dudley kept weather records in Boston for 1729 - 1730. Benjamin Franklin also kept systematic records of the weather and ocean temperature on his return voyage from England in 1739, and he continued keeping records, including while he was Postmaster General of the Colonies. Thomas Jefferson in Monticello, Virginia, and James Madison in Williamsburg, Virginia, made the first intentionally simultaneous weather observations in North America between 1772 and 1777.Official meteorological observation began in the United States on April 2, 1814, when Physician and Surgeon General of the Army Dr. James Tilton (1745 - 1822) ordered hospital surgeons to record the weather. Thus, it was not an expressly created scientific establishment that began written observation of the weather, but the U.S. Army. The Army Surgeon General continued collecting meteorological data after Dr. Tilton retired. Espy was appointed the first official U.S. government meteorologist in 1842, leading to the first official observations and publications by an official U.S. government meteorologist. Based on the foundation of Espy's work, most American meteorology in the subsequent decades evolved.

Publication History and Census

These reports were compiled and written by James Pollard Espy in 1843 (First Report on Meteorology to the Surgeon General of the United States) and 1851 (Second Report on Meteorology to the Secretary of the Navy and the Third Report on Meteorology with Directions for Mariners, etc.). We note 8 examples of the First Report cataloged in OCLC (OCLC 972725478) and the Second and Third Report published together as they are here are well represented in institutional collections (OCLC 1435697). While there are OCLC entries for the Second Report that do not list the Third Report, we believe this to be more likely attributable to cataloging errors than the Second Report being published separately. We have been unable to locate any other examples of all three Reports being bound together in one volume as here. This unique historical artifact was most likely bound together in this manner by the Mercantile Library of Philadelphia, whose stamp appears on several of the sheets within the volume.Cartographer

James Pollard Espy (May 9, 1785 - January 24, 1860) was an American meteorologist. Born in Westmoreland County, Pennsylvania, Espy was the youngest of ten children. His parents moved the family to Kentucky when he was an infant, leading him to enroll at Transylvania University. While a student at Transylvania University in Lexington, Kentucky, Espy taught school to earn a living. He graduated in 1808 and moved to Cumberland, Maryland, where he taught at an academy. At some point he moved to Xenia, Ohio, where he studied and practiced law. He married Margaret Pollard (his 16-year-old cousin) in 1812 and took her maiden name as his middle name. He accepted a position in the classical department at the Franklin Institute in Philadelphia in 1817, where he published his first meteorological research in the Journal of the Franklin Institute.He began studying the causes of storms in 1828, which made him the foremost American meteorologist at the time. Espy became the meteorologist for the Franklin Institute and the American Philosophical Society of Philadelphia in 1834 and in 1836 established a network of meteorological observers to study storms in Pennsylvania, then the most common kind of meteorological research. To support his research, Espy successfully convinced the Pennsylvania Legislature to appropriate $4,000 to supply one observer in each county with a rain gauge, thermometers, and a barometer. After publishing a summary of his work in 1833, Espy became apparently the first person to discuss the role of latent heat in creating and fueling a storm. He abandoned teaching in 1836 in favor of lecturing to scientific bodies and popular audiences, which soon earned him the nickname the 'Storm King'. He published his most famous work The Philosophy of Storms in 1841 and a year later in 1842 he was appointed the first meteorologist of the U.S. government. He served in the U.S. government until 1859 first under the Surgeon General of the Army, then under the Secretary of the Navy, and, finally, the under the Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution beginning in 1848. He retired in 1859 and spent the next few months visiting friends and relatives in Pennsylvania and Ohio. He suffered a stroke in January 1860 while on a visit to Cincinnati, Ohio, and died a week later. More by this mapmaker...