This item below is out of stock, but another example (left) is available. To view the available item, click "Details."

Details

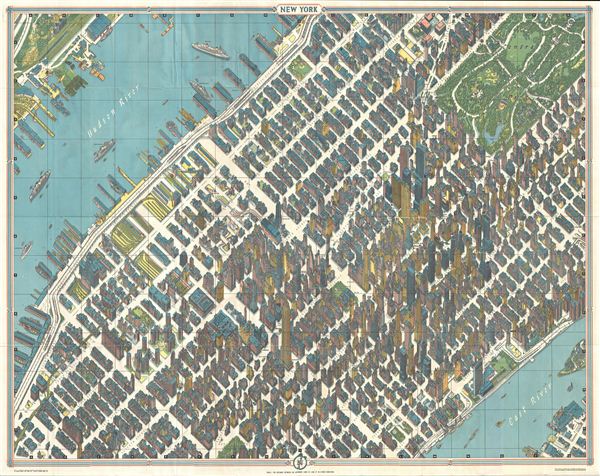

1964 Bollmann View of Midtown Manhattan/ Subway Map on Reverse

1964 (dated) $450.00

1963 Bollmann View and Map of New York City, Midtown

NewYorkGuide-bollmann-1963

Title

1963 (dated) 33 x 42 in (83.82 x 106.68 cm)

Description

In making the map in the 1950s, Herman Bollmann and his staff faced a seemingly insurmountable problem, one never before encountered by his few predecessors in axonometric cartography: how to show New York's many and densely concentrated skyscrapers from the same angle and relative height, while not obscuring most of the city behind them?

He and his team designed and built special cameras to take 67,000 photos, 17,000 from the air. Using these photos as a base, they then began to hand draw the entire city. Using then-secret cartographic techniques, Bollmann and team managed to depict the smallest details while simultaneously conveying the city's soaring, vertiginous beauty.

The viewer is thus placed in the position of an Olympian God, a perspective that no other technologic and artistic form offers, even in the Internet age: with this map spread out before you, you have the ability to look upon any part of the city at will, down to its smallest detail, without waiting for a camera to pan or zoom or cut, without waiting for the next web page to load or zoom.

The closest comparisons are found in poetry or music. Specifically, Homer's epics, a hundred thousand spears hitting a hundred thousand shields at once, while a grain of sand is disturbed by the teardrop of a lover bereft; and Beethoven's dizzyingly monumental perspective, encompassing the whole of human experience and then transcending it in one massive symphonic crescendo, only to be shattered by a single plaintive voice in the next. But neither of these are adequate comparisons to Bollmann's map. As with film or the internet, the experience of poetry and music is limited by linear time. Bollmann's map knows no such constraint.

Perhaps then we must look to architecture and the great buildings of the world to find an analogue to Bollmann's simultaneity of close-up and long-shot, of Olympian and human. One thinks first of the soaring arches of Gothic cathedrals-- arcing up towards heaven, defying physical gravity, incredible weight and incredible lightness. Yet Gothic surfaces are not detailed enough to invite comparison to Bollmann, there is only contemplation of the grand.

So too in the more superficially ornate Hagia Sophia in Istanbul, with its spaces within spaces, all leading up, to greater and greater light, or India's exquisitely detailed Taj Mahal. While these all capture the monumentality of Bollmann's staggering axonometric perspective, their surfaces do not invite interaction, and somehow, something human in us is denied. These are spaces we can admire, but not spaces we can imagine living in.

Which architecture is both detailed and grand, monumental and human? The Baroque style is both ornate and vertiginous, grand yet emotionally involved. But are not the Baroque's polarities of human to God precisely opposite to Bollmann?

The emotion in Bollman arises in response to the God-like precision and geometry, the dizzying height; Bollman's absence of humans, by strange contrast, invite one's humanity to flower and explore.

What is disturbing in the Baroque is the heights and pitch of emotion reached by the humans or human forms it depicts (one thinks specifically of certain churches in Munich). Anguished angels and demons, in human form, hang from places humans can never and should never be, high up on massive columns, hanging from ceilings, arches. One's eyes grasp at any symmetry or geometry one can find (one remembers certain churches in Munich).

Bollmann's map, by contrast, while devoid of people, invites life, suggesting a Situationists labyrinth, inviting the viewing to stroll its curiously emptied, widened boulevards, to adventure behind the skyscrapers and spires.

Perhaps the closest analogy one can draw to the spirit of Bollmann is in abstract expressionism. In a very different way, abstract expressionist paintings can also suggest Lovecraftian perspectives beyond the human, while, in the fragile brushstrokes themselves, evoke the tenderest sympathy for people, in all of their idiosyncratic imperfection.

But we digress.

The guidebook-- written in english, French, German, Spanish, Italian and Japanese-- lists sights, hotels, restaurants and shops, making the work a valuable time capsule to a vanished city. One of the crowning glories of modern cartography, this stunning achievement is a must-have for those who love New York, bird's eye view and the history of cartography.

Cartographer

Herman Bollmann (1911 - 19??) was a German cartographer and map maker active from roughly 1940 to 1970. Prior to World War II, Bollmann was a well-known woodcarver and engraver based in Braunschweig, Germany. Following the war Bollmann developed a reputation as a printer of unique three dimensional maps. Working over a period of 25 years, Bollmann established a reputation as an artistic cartographer, producing over 39 unique projections of various cities in Europe and America. Bollmann revived the 19th century cartographic technique known as Vogelschaukarten, a way of making three dimensional axonometric projections. Bollmann and his team relied heavily on aerial cartography to compose distinctive cartographic masterpieces that are coveted by collectors all over the world. More by this mapmaker...