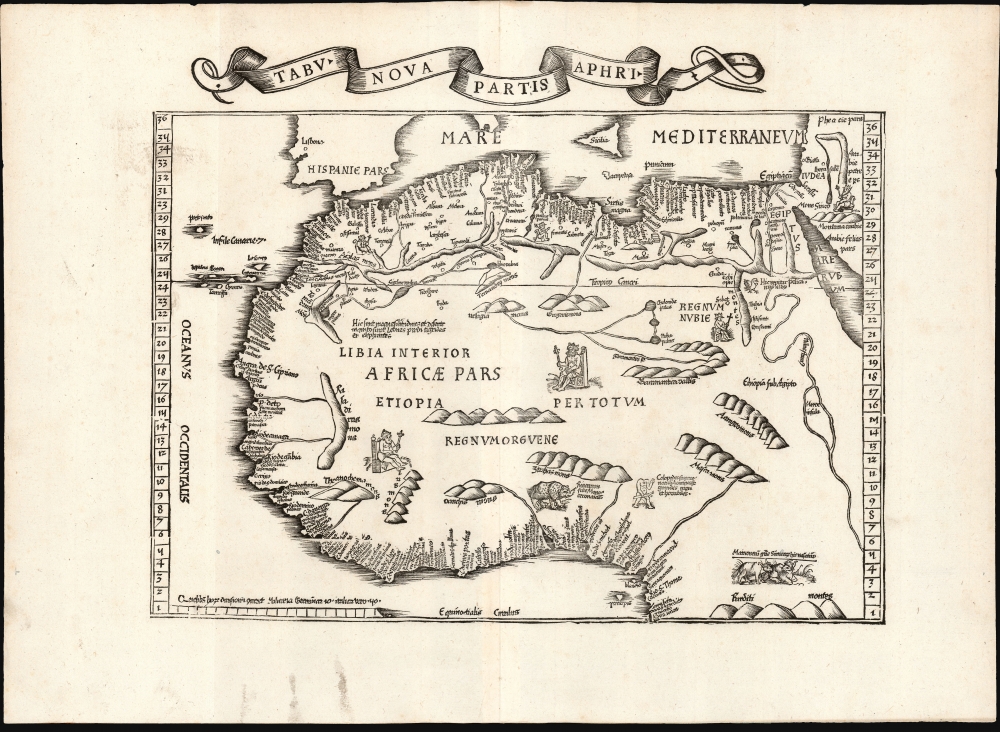

1522 / 1525 Waldseemüller / Fries map of Northern Africa

NorthAfrica-waldseemullerfries-1522

Title

1522 (undated) 12.5 x 15.5 in (31.75 x 39.37 cm) 1 : 15000000

Description

A Closer Look

It is based geographically on Martin Waldseemüller's 1513 Tabula Moderna Prime Partis Aphrica while incorporating text and imagery from the same geographer's 1516 Carta Marina. Overall, the map captures Waldseemüller's efforts to reconcile the data of the ancient geographical authority Claudius Ptolemy with new information available from Portuguese exploration of the late 15th and early 16th century. Fries' edition, first printed in 1522, in the past, has been dismissed as merely a decorative version of the 1513. However, it represents his own effort to unify Waldseemüller's various works in order to produce a more broadly informative work.Earliest Modern Mapping of North Africa

The map depicts Africa north of the Equator. While maps of this part of the world were printed prior to Waldseemüller's, these were entirely Ptolemaic works: up until the printing of his 1513 map, all maps of Africa were based on data from the second century. After Portugal began to probe southwards along the African coast, maps began to reflect some of the new knowledge, such as the world map gracing the 1482 edition of Mela's Cosmographi Geographia De Situ Orbis. Waldseemüller's world maps of 1507 and 1516, incorporated for the first time on a printed map the coastal names derived from Portuguese manuscript maps - most likely the 1502 Cantino Planisphere or a close relative. The 1513 Tabula Moderna is the first separate map of Africa based on that new information.The Scope and Content of the Map

The map, a skillful and attractive woodcut, depicts Africa from the Mediterranean Sea about 34° north to the Equator. Longitude is not specified, but the mapped region spans from the Canary Islands in the west to the Red Sea in the east. The African Mediterranean coastline and the western coast as far south as the Bight of Benin reflect the Cantino Planisphere. In this, both the present work and the 1513 agree with Waldseemüller's 1516 Carta Marina but not his more famous 1507 world map. That work's North African coastline remained faithful to Ptolemy's topography, appending new geographical information in the south where the Ancient's data petered out.The interior, however, does not benefit greatly from modern knowledge. The Cantino Planisphere could offer very little: its depiction of the continent's interior was entirely pictorial. The mountain ranges and river systems appearing on this map, as well as its 1507 and 1513 precursors, derive from Ptolemy - variations on this geography can be found with variations on all editions of Ptolemy's Tabula Quarta Africae. In an odd lapse, Fries did not adopt the new geography south of 16° appearing on the Carta Marina: the 1516 map shows a River Senegal extending far into the interior, where the rivers deriving from Ptolemaic iterations (such as the present work) end in mountains appearing relatively close to the coastline.

Nevertheless, many elements on this map - the seated kings and the Rhinoceros - reveal connections with Waldseemüller's 1516 Carta Marina, despite his geographical adherence here to the 1513 map. One text block - describing a region of large deserts and wildernesses in which there are lions, leopards, tigers, and elephants - appears on all of Waldseemüller's maps of this region, including the 1507 and 1516 world maps. Others appear only on the Carta Marina before this map, notably the text north of the Bight of Benin, describing the Cyclopes reputed to live there. (Cyclopes or one-eyed men - they are big and black and horrible.) Fries' map not only includes the text but also supplies an image of such a creature, with its eye (as with a blemmyae) in its chest. Unlike the broad outline of the map, these details do not ultimately derive from the Cantino Planisphere, and Waldseemüller's source for them is not clearly known. Waldseemüller's placement of the Cyclops in Africa influenced other mapmakers, notably Sebastian Münster, who would also prominently display the monster in his own map.

Publication History and Census

This map was first issued in the 1522 Lorenz Fries Strasbourg edition of Ptolemy's Geographia. A further edition was produced in that same city in 1525. Afterward, two further editions of 1535 and 1541 were published in Lyons and Vienne-in-the-Dauphane, respectively. The editor of the 1535 edition, Michael Villanovus (Servetus), was tried for heresy in 1553 and burned at the stake. Reportedly, Calvin ordered copies of the Servetus edition burned. Consequently, maps from the 1535 edition (of which this is a representative) are scarce. Overall, the four editions of Fries' Ptolemy are well represented in institutional collections. We see seven separate examples of this edition of the map in OCLC.CartographerS

Lorenz Fries (c. 1490 – 1531) was a German cartographer, cosmographer, astrologer, and physician based in Strasbourg. Little is known of Fries' early life. He may have studied in Padua, Piacenza, Montpellier, and Vienna, but strong evidence of this is unfortunately lacking. The first recorded mention of Fries on a 1513 Nuremberg broadside. Fries settled in Strasbourg in March of 1519, where he developed a relationship with the St. Die scholars, including, among others, Walter Lud, Martin Ringmann, and Martin Waldseemüller. There, he also befriended the printer and publisher Johann Grüninger. Although his primary profession was as a doctor, from roughly 1520 to 1525, he worked closely with Grüninger as the geographic editor of various maps and atlases based upon the work of Martin Waldseemüller. Although his role is unclear, his first map seems to have been a 1520 reissue of Waldseemüller's world map of 1507. Around this time, Fries also began working on Grüninger's reissue of Waldseemüller's 1513 edition of Ptolemy's Geographie Opus Novissima. That edition included three new maps by Fries based upon the Waldseemüller world map of 1507 – two of these, his maps of East Asia and Southeast Asia, are quite significant as the first specific maps of these regions issued by a European publisher. In 1525, Fries decided to leave Strasbourg and surrendered his citizenship, relocating to Trier. In 1528, he moved to Basel. Afterward, he relocated to Metz where he most likely died. In addition to his cartographic work, Fries published tracts on medicine, religion, and astrology. More by this mapmaker...

Martin Waldseemüller (September 11, 1470 - March 16, 1520) was a German cartographer, astronomer, and mathematician credited with creating, along with Matthias Ringmann, the first map to use the placename America. He was born in Wolfenweiler, near Freiburg im Breisgau. Waldseemüller studied at the University of Freiburg and, on April 25, 1507, became a member of the Gymnasium Vosagese at Saint-Dié. Martin Waldseemüller was a major proponent of theoretical or additive cartography. Unlike contemporary Portuguese and Spanish cartographers, who left maps blank where knowledge was lacking, Waldseemüller and his peers speculated based upon geographical theories to fill unknown parts of the map. He is best known for his Universalis Cosmographia a massive 12-part wall map of the world considered the first map to contain the name America, today dubbed as 'America's Birth Certificate'. This map also had significance on other levels, as it combined two previously unassociated geographical styles: Ptolemaic Cartography, based on an ancient Greek model, and the emergent 'carta marina', a type of map commonly used by European mariners in the late 15th and 16th centuries. It also extended the traditional Ptolemaic model westward to include the newly discovered continent of America, which Waldseemüller named after the person he considered most influential in its discovery, Amerigo Vespucci. When Waldseemüller died in 1520, he was a canon of the collegiate Church of Saint-Dié. In contemporary references his name is often Latinized as Martinus Ilacomylus, Ilacomilus, or Hylacomylus. Learn More...