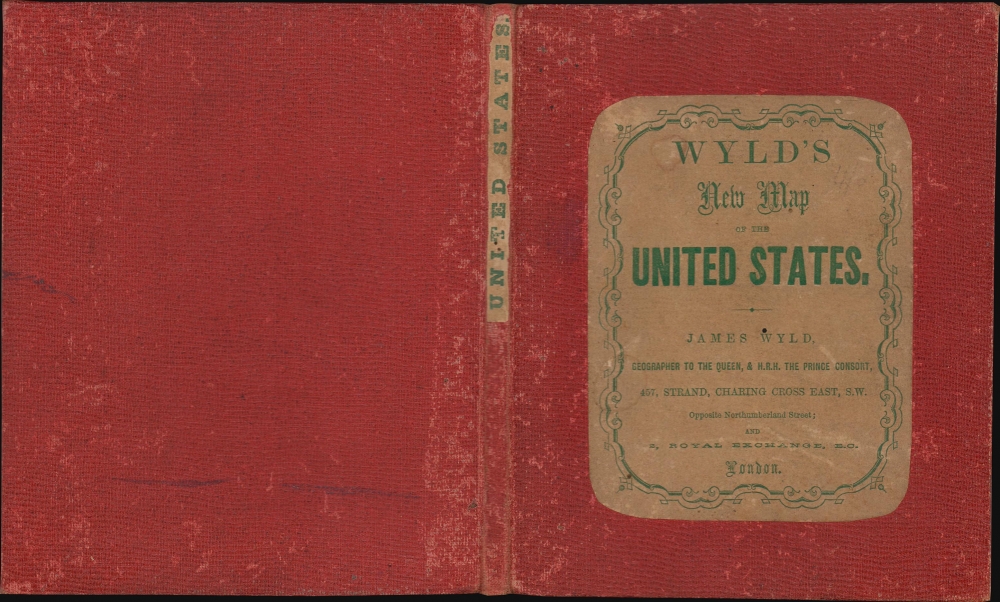

1861 Wyld Map of the United States during the American Civil War

NorthernSouthernConfed-wyld-1861

Title

1861 (undated) 15.75 x 22 in (40.005 x 55.88 cm) 1 : 10000000

Description

A Closer Look

Illustrating the country near the war's outset, Wyld uses color to emphasize the national divide. States and territories are labeled, including the unincorporated territory of Dacotah (although it isn't configured as we would expect). The railroad network appears in detail, with the striking difference in railroad density between the North and the South starkly apparent. Cities and towns are labeled in the east, with only a handful of cities marked in the western territories, along with many Army forts. Confederate Arizona appears in the southwestern portion of the country, splitting what had been the New Mexico Territory in half. Population tables divided by state occupy the lower left corner, while similar population statistics, along with statistics concerning slaveholding, appear along the right border below an inset map of Great Britain. This inset appears to provide the British audience (for whom this map was intended) with an understandable scale of just how large the United States was. Finally, along the bottom border at center, a last statistical table provides export figures for the United States from 1858.Confederate Arizona

Confederate Arizona was a territory claimed by the Confederate States of America from 1861 until 1865. The idea for an Arizona Territory appears as early as 1856, when the government of New Mexico began to express concerns about being able to effectively govern the southern part of the territory, as it was separated from Santa Fe by the Jornada del Muerto, a particularly unforgiving stretch of desert. The New Mexico territorial legislature acted on these concerns in February 1858, approving a resolution in favor of creating an Arizona Territory, with a north-south border to be defined along the 32nd meridian (from Washington). Impatiently waiting for Congress to approve the creation of the new territory, 31 delegates met at a convention in Tucson in April 1860 and drafted a constitution for the 'Territory of Arizona', which was to be organized out of the New Mexico Territory below 34th parallel. The convention elected a territorial governor and a delegate to Congress. Congress, however, was reluctant to act. Anti-slavery Representatives knew that the proposed territory was located below the line of demarcation set forth by the Missouri Compromise for the creation of new slave and free states, and they were not inclined to create yet another slave state. Thus, Congress never ratified the proceedings of the Tucson convention, and the Provisional Territory was never considered a legal entity.At the beginning of the Civil War, support for the Confederacy ran high in the southern parts of the New Mexico Territory. Local concerns drove this sentiment, including a belief that the war would lead to an insufficient number of Federal troops to protect the citizens from the Apache, while others simply felt neglected by the government in Washington. Also, the Butterfield Overland Mail Route (an overland mail and stagecoach route from Memphis and St. Louis to San Francisco) was closed in 1861, depriving the people of Arizona of their connection to California and the East Coast.

All these factors led to the people of the southern New Mexico Territory, or the Arizona Territory, to formally call for secession, and a convention adopted a secession ordinance on March 16, 1861, with a subsequent ordinance ratified on March 28, establishing the provisional territorial government of the Confederate 'Territory of Arizona'. The Confederate Arizona Territory was officially proclaimed on August 1, 1861, following Lieutenant-Colonel J. R. Baylor's victory over Union forces in the First Battle of Mesilla, and the territory was officially recognized by the government of the Confederacy on February 14, 1862. However, by July 1862, Union forces from California, known as the 'California Column' were marching on the territorial capital of Mesilla. Sent to protect California from a possible Confederate incursion, the 'California Column' drove Confederate forces out of the city, allowing them to retreat to Franklin, Texas. The territorial government fled as well and spent the rest of the war in 'exile'. First, they retreated to Franklin, then, after Confederate forces abandoned Franklin and all of West Texas, to San Antonio, where the 'government-in-exile' would spend the rest of the war. Confederate units from Arizona would fight for the rest of the war, and the delegate from Arizona attended both the First and Second Confederate Congresses.

The Unincorporated Territory of 'Dacotah'

During the nearly three year period between Minnesota's statehood on May 11, 1858 and the creation of the Dakota Territory on March 2, 1861, the portion of what had been the Minnesota Territory that fell between the Missouri River and Red River (Minnesota's newly-created western border), remained unattached to any official territory of the United States. Immediately following Minnesota's statehood, a provisional government was set up in the Pembina Region which lobbied for recognition as a territory. In doing so, a formally recognized local government would be in place, which is an important part of encouraging settlement in a region. Even so, the proposal was mostly ignored by the Federal government until the Dakota Territory was formed, which upon its creation included most of present-day Montana, Wyoming, and both North and South Dakota.British Interest in the Secession

The rise of the Confederacy and the impending American Civil War was briefly a matter of the greatest interest in England. On one hand, most British citizens deplored the practice of slavery, which had been abolished in the British Empire since 1833. On the other hand, the large and influential British textile industry relied heavily on cotton imports from the southern states and there was legitimate concern that failure to recognize the Confederate secession would disrupt supply and lead to economic instability. They were right and the subsequent Lancashire Cotton Famine (1861 - 1865) corresponded exactly with the Civil War. (Within a year Lancashire mill workers went from being the most prosperous in Britain to the most impoverished.) This map would have been of the utmost interest to parties on both sides of the debate. Ultimately, although a near thing, the British Parliament never recognized the Confederacy.Class Distinctions in Britain and Support for the Confederacy

Sympathies in Britain towards the American Civil War were generally broken down according to class and social rank. Quoting historian Douglas Gardner in his review of R. J. M. Blackett's Divided Hearts: Britain and the American Civil War,The more conservative - and Conservative - members of British society, drawn mostly from the aristocracy and the upper reaches of the middle classes, tended to be supporters of the Confederacy in the American conflict and scornful of the possibilities of liberalism or democracy at home. Many of the spokespeople for this group accepted and publicized the Southern apology for slavery as the basis of a properly hierarchical society. Those in the middle - Liberals whose spokespeople often were dissenting ministers or members of the growing professional groups - tended to support the Union but held and displayed a variety of views on race, slavery, and democracy. Working-class spokespeople tended to abhor slavery as another system of human exploitation, and they for the most part stood firm to these beliefs even during the Cotton Famine and other war-related economic dislocations. Less certain was the loyalty of workers (as opposed to their spokespeople) to the antislavery cause.

Wyld's News Maps

Wyld was particularly masterful at capturing political events throughout the world as they happened and leveraging his impressive publishing operation to quickly produce and distribute pertinent maps to the invested public. The speed with which Wyld was able to assess news events and produce an informative and new fully engraved map contributed significantly to his commercial success. Wyld's news maps, while a small subset of his large cartographic corpus, arguably represent his most significant work - forming a vital record of currently developing new events from an even-handed if Anglo-centric perspective. Such maps had an ephemeral period of interest, were separately issued, and necessarily printed in small quantities, leading to their extreme scarcity today.Publication History and Census

This map was created and published by James Wyld in 1861. We note examples cataloged in OCLC: Yale University, the University of California Santa Barbara, the University of Texas at Arlington, the University of California Santa Barbara, and Stanford University. The map was issued both separately, as here, and as an optional supplement to Wyld atlases. The edition at the Yale University Library bears a manuscript notation that includes the date '10/12/61', letting us assign a date to the present example.Cartographer

Wyld (1823 - 1893) was a British publishing firm active throughout the 19th century. It was operated by James Wyld I (1790 - 1836) and his son James Wyld II (November 20, 1812 - 1887) were the principles of an English mapmaking dynasty active in London during much of the 19th century. The elder Wyld was a map publisher under William Faden (1749 - 1836) and did considerable work on the Ordinance Survey. On Faden's retirement in 1823, Wyld took over Faden's workshop, acquiring many of his plates. Wyld's work can often be distinguished from his son's maps through his imprint, which he signed as 'Successor to Faden'. Following in his father's footsteps, the younger Wyld joined the Royal Geographical Society in 1830 at the tender age of 18. When his father died in 1836, James Wyld II was prepared to fully take over and expand his father's considerable cartographic enterprise. Like his father and Faden, Wyld II held the title of official Geographer to the Crown, in this case, Queen Victoria. In 1852, he moved operations from William Faden's old office at Charing Cross East (1837 - 1852) to a new, larger space at 475 Strand. Wyld II also chose to remove Faden's name from all of his updated map plates. Wyld II continued to update and republish both his father's work and the work of William Faden well into the late 1880s. One of Wyld's most eccentric and notable achievements is his 1851 construction of a globe 19 meters (60 feet) in diameter in the heart of Leicester Square, London. In the 1840s, Wyld also embarked upon a political career, being elected to parliament in 1847 and again in 1857. He died in 1887 following a prolific and distinguished career. After Wyld II's death, the family business was briefly taken over by James John Cooper Wyld (1844 - 1907), his son, who ran it from 1887 to 1893 before selling the business to Edward Stanford. All three Wylds are notable for producing, in addition to their atlas maps, short-run maps expounding upon important historical events - illustrating history as it was happening - among them are maps related to the California Gold Rush, the New South Wales Gold Rush, the Scramble for Africa, the Oregon Question, and more. More by this mapmaker...