This item has been sold, but you can get on the Waitlist to be notified if another example becomes available, or purchase a digital scan.

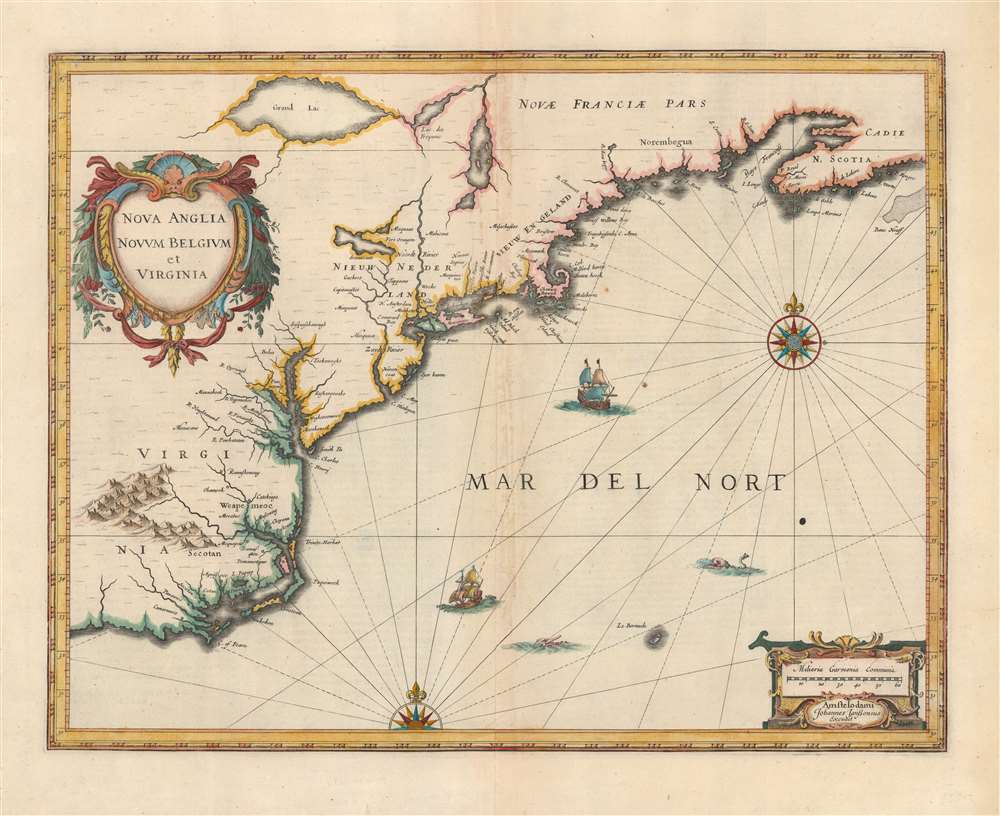

1636 Jansson Map of New York, Virginia, and New England

NovaAngliaNovumBelgiumVirginia-jansson-1636-3

Title

1636 (undated) 15.5 x 20 in (39.37 x 50.8 cm) 1 : 5200000

Description

State-of-the-art Cartography

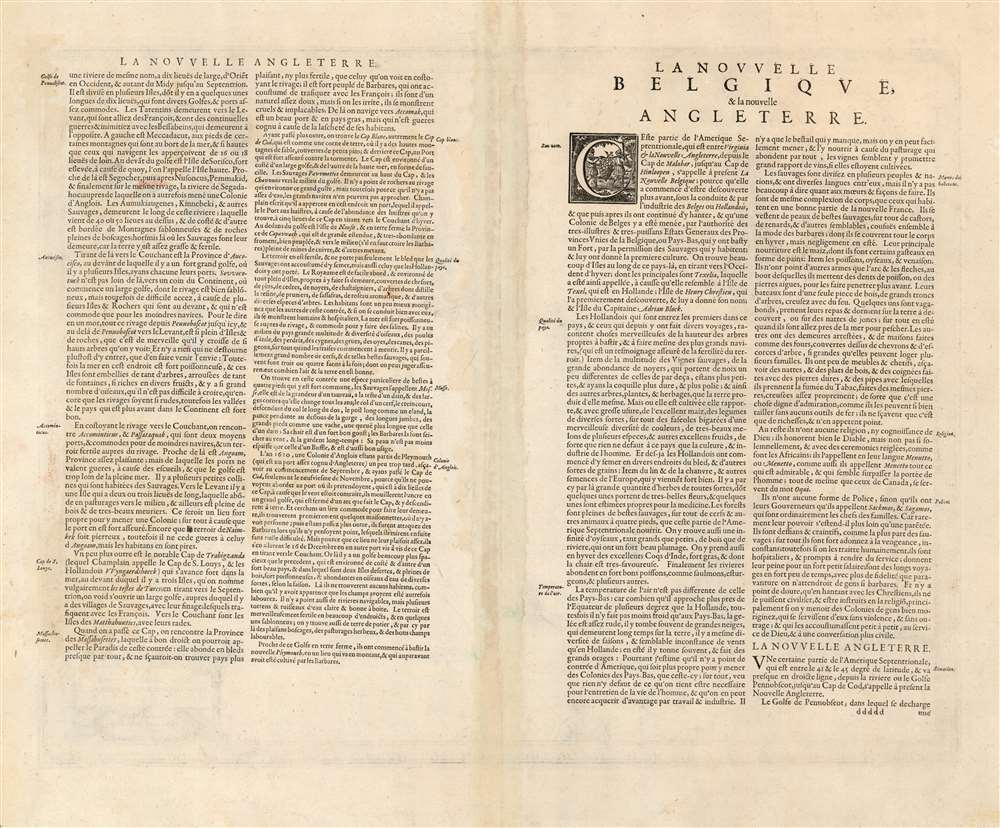

Jansson's map is a faithful, expanded copy of the much scarcer 1630 map published by Johannes de Laet and drawn by the Dutch chartmaker Hessel Gerritsz, although Jansson also enlarged the scope of his map to cover additional lands to the north and west. Jansson's adherence to the Gerritz model extended to his verbatim transcription of de Laet's verso text describing the region. The map presents the conflicting colonial spheres of influence of England, the Netherlands, and France. The position of the New Netherlands can either be seen as boldly splitting English interests in twain, perilously surrounded by the British colonies in Virginia and New England. The cartography ere with its illustration of Manhattan as an island, and the early appearance of Fort Orange, was soon to be supplanted by the competing Blaeu map, whose Adriaen Block-derived cartography outpaced the Gerritz model.A Broad Scope

Jansson's map is centered on the New Netherlands, showing the Hudson Valley as far north as Albany (Fort Orange) sandwiched between English colonies in Nieuw Engeland (New England) and Virginia (Jamestown). West of the Hudson is a speculative treatment of the upper Delaware River, offer an array of tribal names. The closest lake to New Amsterdam, identified as Seccecaas, after the Seneca, an Iroquois people, most likely represents Lake Oneida, which European trappers may have heard of from their American Indian trading partners but would not have encountered directly. The lakes further north, Lake Iroquois (Yroquois), Grand Lac, and a third unnamed lake, doubtless represent some combination of Lake Champlain and the Great Lakes. As this map was being drawn, English and Dutch trappers were in fierce competition over the Hudson, Connecticut (here Versche Rivier), and Delaware (here Zuydt Rivier) River peltries. These rivalries escalated into the 1664 English takeover of New Amsterdam and its subsequent renaming as New York. While Gerritz and consequently Jansson were not ignorant of Samuel de Champlain's discoveries in the north, these did not appear on the Gerritz/De Laet map upon which this map was based, but rather on a map dedicated to the mouth of the Saint Lawrence and the Maritimes. It is possible that the separation here of French claims from those of the English and Dutch was deliberate, but the French were not clear on the northern extent of the Hudson, and the Dutch were not clear on the positioning of Lake Champlain and Lake George in relation to the Hudson River Valley. The application of the place name 'Lac des Yroquois' to a proto-Lake Erie is unusual: this name would later usually refer to Lake Champlain. The largest lake, 'Grand Lac' is a matter of some dispute. Karpinski suggests this is the first map to depict Lake Superior in full, but Burden asserts that there is no evidence to suggest this as Lake Superior. To our eye, it is most likely an embryonic representation of either Lake Erie or Lake Huron, or some amalgam of both. Regardless of which lakes are represented, Jansson's map remains one of the earliest Dutch attempts to show any Great Lake at all.The El Dorado of the North

The region of modern-day Maine is identified using the archaic term Norembegua. This mysterious land appeared on many early maps of New England starting with Verrazano's 1529 manuscript map of America. He used the term, Oranbega, which in Algonquin means something on the order of 'lull in the river'. The first detailed reference to Norembegua, or as it is more commonly spelled Norumbega, appeared in the 1542 journals of the French navigator Jean Fonteneau dit Alfonse de Saintonge, or Jean Allefonsce for short. Allefonsce was a well-respected navigator who, in conjunction with the French nobleman Jean-François de la Roque de Roberval's attempt to colonize the region, skirted the coast south of Newfoundland in 1542. He discovered and apparently sailed some distance up the Penobscot River, encountering a fur rich American Indian city named Norumbega - somewhere near modern-day Bangor, Maine.The river is more than 40 leagues wide at its entrance and retains its width some thirty or forty leagues. It is full of Islands, which stretch some ten or twelve leagues into the sea. ... Fifteen leagues within this river there is a town called Norombega, with clever inhabitants, who trade in furs of all sorts; the town folk are dressed in furs, wearing sable. ... The people use many words which sound like Latin. They worship the sun. They are tall and handsome in form. The land of Norombega lies high and is well situated.Though Roberval's colony lasted only two years, Andre Thevet, writing in 1550, records encountering a French trading fort at the site of Norumbega. A few years later in 1562, an English slave shipwrecked in the Gulf of Mexico. David Ingram, one of the survivors, claimed to have trekked overland from the Gulf Coast to Nova Scotia where he was rescued by a passing French ship. Possibly inspired by Mexican legends of El Dorado, Cibola, and other lost cities, Ingram returned to Europe to regale his drinking companions with boasts of a fabulous city rich in pearls and built upon pillars of crystal, silver, and gold. The idea caught on in the European popular imagination and expeditions were sent to search for the city - including that of Samuel de Champlain.

The legend of Norumbega thus seems to have transitioned from Allefonsce's most likely factual description of a lively American Indian fur trading center, to Thevet's French trading fort, to Ingram's fabulous paradise dripping in wealth. Allefonsce's description of the American Indians he encountered in Norumbega corresponds well with those of Hudson, who also met a tall well-proportioned people. Sadly only a few years later many of these tribes began to die off at extraordinary rates (over 90% of the population perished) due to horrifying outbreaks of smallpox and other diseases carried by the unwitting European explorers. It seems reasonable that Allefonsce may have stumbled upon a periodic or semi-permanent indigenous fur trading center on the Penobscot. It also seems reasonable that French colonists may have set up their fur trading post at the same site, for it was fur, not gold, that was the real wealth of New England and Norumbega. Alas, it was Ingram's fictitious account, which though wholly the product of drunken sailor's imagination, produced the most enduring image of Norumbega.

Virginia

In the Chesapeake Bay region and further south, Jansson offers some detail regarding the complex river systems. English settlement in the region is limited to Jamestown, although American Indian villages are well represented and thorough. Gerritz' geography for the Carolinas is mostly derived from the impressive 1590 John White map. However, the Chesapeake region has been updated to reflect John Smith's map, which was by the 1630s well known in the Netherlands, copies of it having been produced by Hondius, Blaeu, and Jansson alike. The mountains presented inland, while attractive, are largely speculative or based upon American Indian geographic descriptions.A Beautiful Engraving

The large, botanically themed title cartouche in the upper left is the major distinguishing feature used to distinguish this, the first state. The appearance of Blaeu's map - the first map of the region to be lavishly decorated with animals and natives - led to the reworking of this plate to compete with Blaeu via the expedient plagiarism of the decorative features in question. Thus this first state of Jansson's map represents a more original aesthetic than what would follow. The latter states copy Blaeu's title. Nevertheless, the present example is graced with sailing ships, two elegant compass roses, and a fine secondary cartouche in the lower right featuring Jansson's imprint as well as a distance scale in German miles.Publication History and Census

This map was first engraved for inclusion in the 1636 Appendix Atlantis Oder dess Welt Buchs and was included in editions of the Hondius/Jansson atlases until 1675. The present example is of the 1639 first French edition of Hondius' Nouvel Atlas. We see five examples of this French-text edition in OCLC. The map is well represented in its other editions.CartographerS

Jan Jansson or Johannes Janssonius (1588 - 1664) was born in Arnhem, Holland. He was the son of a printer and bookseller and in 1612 married into the cartographically prominent Hondius family. Following his marriage he moved to Amsterdam where he worked as a book publisher. It was not until 1616 that Jansson produced his first maps, most of which were heavily influenced by Blaeu. In the mid 1630s Jansson partnered with his brother-in-law, Henricus Hondius, to produce his important work, the eleven volume Atlas Major. About this time, Jansson's name also begins to appear on Hondius reissues of notable Mercator/Hondius atlases. Jansson's last major work was his issue of the 1646 full edition of Jansson's English Country Maps. Following Jansson's death in 1664 the company was taken over by Jansson's brother-in-law Johannes Waesberger. Waesberger adopted the name of Jansonius and published a new Atlas Contractus in two volumes with Jansson's other son-in-law Elizée Weyerstraet with the imprint 'Joannis Janssonii haeredes' in 1666. These maps also refer to the firm of Janssonius-Waesbergius. The name of Moses Pitt, an English map publisher, was added to the Janssonius-Waesbergius imprint for maps printed in England for use in Pitt's English Atlas. More by this mapmaker...

Hessel Gerritsz (1581 – September 4, 1632) was a Dutch engraver, cartographer, and publisher active in Amsterdam during the late 16th and early 17th centuries, among the most preeminent Dutch geographers of the 17th century. He was born in Assum, a town in northern Holland in 1581. As a young man he relocated to Alkmaar to accept an apprenticeship with Willem Jansz Blaeu (1571-1638). He followed Blaeu to Amsterdam shortly afterwards. By 1610 he has his own press, but remained close to Blaeu, who published many of his maps. In October of 1617 he was appointed the first official cartographer of the Vereenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie (Dutch East Indian Company) or VOC. This strategic position offered him unprecedented access to the most advanced and far-reaching cartographic data of the Dutch Golden Age. Unlike many cartographers of his period, Gerritsz was more than a simple scholar and showed a true fascination with the world and eagerness to learn more of the world he was mapping in a practical manner. In 1628 he joined a voyage to the New World which resulted in the production of his seminal maps, published by Joannes de Laet in his 1630 Beschrijvinghe van West-Indien; these would be aggressively copied by both the Blaeu and Hondius houses, and long represented the standard followed in the mapping of the new world. Among his other prominent works are a world map of 1612, a 1613 map of Russia by the brilliant Russian prince Fyodor II Borisovich Godunov (1589 – 1605), a 1618 map of the pacific that includes the first mapping of Australia, and an influential 1630 map of Florida. Gerritsz died in 1632. His position with the VOC, along with many of his printing plates, were taken over by Willem Janszoon Blaeu. Learn More...

Johannes de Laet (1581 – December 15, 1649) was a Dutch businessman and cartographer active in Leiden during the early 17th century. De Laet was a Flemish Protestant born in Antwerp to a prosperous merchant family in the cloth trade. When Antwerp fell to the Catholic Spanish in August of 1585, he and his family fled to the northern Netherlands. At the University of Leiden, he studied Theology and Philosophy, matriculating in 1597. In 1603 he relocated to London, where he acquired denizenship, an early type of citizenship and married. His Anglo-Dutch wife died shortly afterward and he returned to Leiden, where he married again. He cleverly invested in Dutch land reclamation projection and the overseas trade, becoming extremely wealthy. In 1620, he became a founding director of the Dutch West Indies Company, a position he held until his death. His most important cartographic work, Nieuwe Wereldt ofte Beschrijvinghe van West-Indien has been hailed by the map historian Phillip Burden as 'arguably the finest description of the Americas published in the 17th century. It contained several seminal maps of the Americas that significantly advanced cartographic perspectives on the region and served as a foundational work for subsequent cartographers. De Laet died in Den Haag (The Hague) in 1649. Learn More...