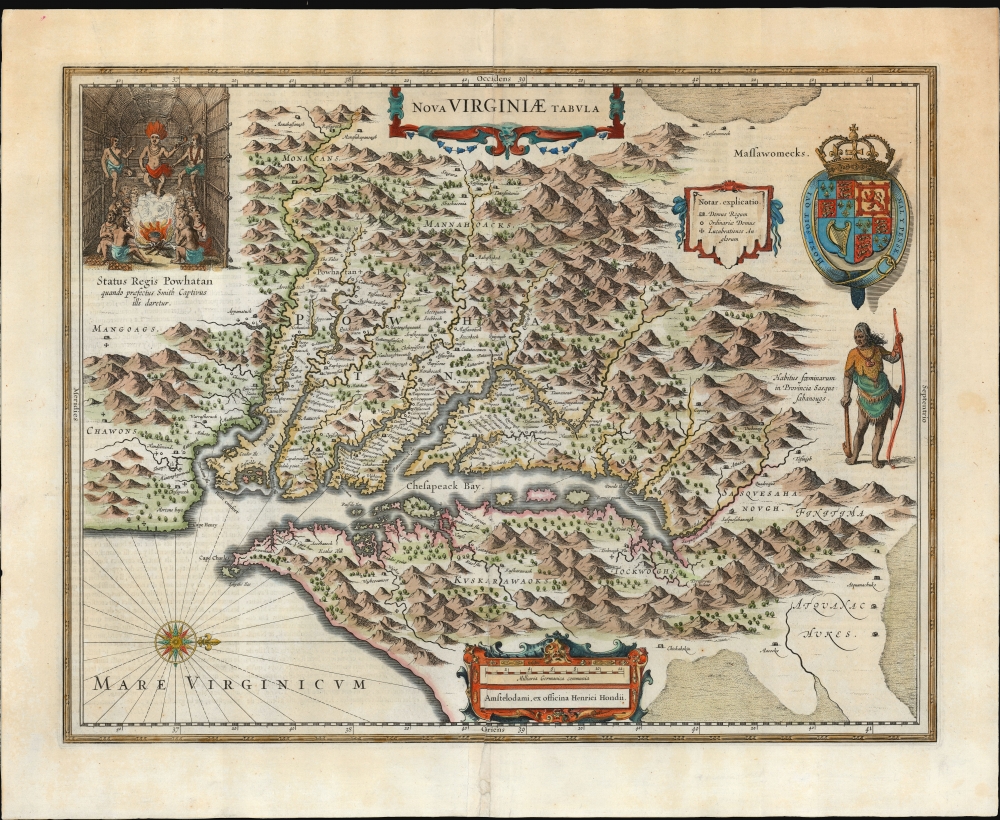

1630 Hondius Map of Virginia and the Chesapeake

NovaVirginiaeTabula-hondius-1630-2

Title

1630 (undated) 15.5 x 19.5 in (39.37 x 49.53 cm) 1 : 1680000

Description

A Closer Look

As with its progenitor, Hondius' map is oriented to the west (in the case of the Smith map, this was largely a chartmaking convention: presenting the coastline as it would be approached by sea.) The map spans from Cape Henry in the south to the Susquehanna River and reaches inland as far as the Appalachian Mountains. The Chesapeake Bay is shown in full, as are many of its river estuaries. While well-informed with respect to waterways, the beautiful mountains depict ranges where there are, in fact, none. In the upper right of the map are the map's key, the British Royal Arms, and a depiction of a warrior of the Susquehanna tribe.In the upper left quadrant is a depiction of the chief of the Powhatan people, sitting enthroned before a great fire in his longhouse. Powhatan was the chief of the famed legend regarding the capture and trial of John Smith and Smith's fabled liberation at the behest of the chief's daughter, Pocahontas. Romantic tales aside, it is likely that Powhatan saw Smith and his Englishmen as potential allies against the rival American Indian groups, such as the Massawomecks and the Susquehanna, that were pressing hard against his borders.

Smith did contact and trade with both these neighboring tribes. The Susquehanna impressed the diminutive (5' 3') Smith with their size: on his map, the depiction of their warrior included the text 'The Sasquehanougs are a Gyant-like people and thus attired.' (Puzzlingly, the text on the Dutch versions of the Smith all identify the Susquehanna figure differently: Habitus foeminarum in Provincia Sasqusahanougs, 'The dress of women in the province of Sasqusahanougs.' ) Smith's interactions with these other tribes expanded the reach of the present map well beyond what his fellow colonists could reach on their own. The crosses marked along the rivers on the map signify Lucubrationes Anglorum - translating close to 'studies of the English.' The text on the 1612 Smith is more precise: 'To the crosses hath been discovered, what beyond is by relation.' Thus, the crosses show the areas of the map derived from actual European exploration and those about which Smith had only the verbal report of his Indian contacts. Some of this information must have been disappointing - the rivers didn't go all that far. But there were reports, particularly from the Massawomecks, that would have been tantalizing.

How Much Land can be There, Surely?

The great hope of European explorers throughout this period was that some means could be found of quickly traversing North America, or circumventing it entirely, in the effort to reach the Pacific and the wealth of the East Indies and China. Many maps of the 16th century had already proposed a massive bay cutting into North America - the 'Sea of Verrazzano' - easily accessible from the vicinity of Virginia. Indeed, the trade potential for the Virginia colony was entirely dependent upon it being a practical access point to the riches of Asia.Herein lies the importance of the body of water appearing in the land of the Massawomecks. Smith describes this tribe in his The Generall Historie of Virginia, New-England, and the Summer Isles:

Beyond the mountains from whence is the head of the River Patawomeke, the Savages report, inhabit their most mortal enemies, the Massawomecks, upon a great salt water, which by all likelihood is either some part of Canada, some great lake, or some inlet of some sea that falleth into the South Sea. These Massawomekes are a great nation and very populous.... from the French (they) have their hatchets and Commodities by trade.Although Smith relates violent encounters with a Massawomeck raiding party on the Chesapeake, the Massawomeck were a fur-trapping and trading tribe nearly as new to the Chesapeake region as Smith - their homeland was actually Lake Erie. Thus, the 'Massawomeck' body of saltwater appearing on this map can be understood as an early, secondhand depiction of Lake Erie. Smith, on the other hand, hoped for an entirely larger body of water: the Pacific, via the legendary Sea of Verrazzano.

Verazzano's Sea

In 1524, Giovanni da Verrazzano sailed in search of a passage through North America to the Pacific Ocean. While he found nothing he could support with actual exploration, his observations of the barrier islands of the American southeast, the Pamlico Sound, and possibly the Chesapeake Bay, led him to speculate that in places North America was quite narrow, and that in these places only anisthmus separated Atlantic from Pacific. Efforts to depict this on maps illustrate a massive body of water plunging into North America from the Pacific nearly to the mid-Atlantic coastline. This so-called 'Sea of Verrazano' appeared on many 16th-century maps and was suggestive of access to the Pacific from the Atlantic. European mapmakers and explorers - in particular, John Smith and Henry Hudson - hung their hopes on discovering the Verrazano Sea, an assumption that colored interpretations of what they discovered. Smith's map reflects his hope that only short marches separated Jamestown from large navigable bodies of water to the west and north. Smith reported as much in a 1609 letter to Henry Hudson, and Hudson acted on this intelligence, sailing for the 40°parallel and discovering the river that now bears his name. In the minds of most Europeans of the period, the trade potential for the Virginia colony was entirely dependent upon it being a practical access point to the riches of Asia.Publication History and Census

This map was engraved in 1630 for inclusion in Hondius atlases; it appears in all subsequent editions with no changes to the plate. The present example conforms typographically to the 1639 French-text Nouvel Theatre du Monde. Both the separate map and the atlases are well represented in institutional collections; the map appears on the market with some regularity, but examples of this quality are increasingly difficult to find.CartographerS

Jodocus Hondius (October, 14 1563 - February 12, 1612) was an important Dutch cartographer active in the late 16th and early 17th centuries. His common name, Jodocus Hondius is actually a Latinized version of his Dutch name, Joost de Hondt. He is also sometimes referred to as Jodocus Hondius the Elder to distinguish him from his sons. Hondius was a Flemish artist, engraver, and cartographer. He is best known for his early maps of the New World and Europe, for re-establishing the reputation of the work of Gerard Mercator, and for his portraits of Francis Drake. Hondius was born and raised in Ghent. In his early years he established himself as an engraver, instrument maker and globe maker. In 1584 he moved to London to escape religious difficulties in Flanders. During his stay in England, Hondius was instrumental in publicizing the work of Francis Drake, who had made a circumnavigation of the world in the late 1570s. In particular, in 1589 Hondius produced a now famous map of the cove of New Albion, where Drake briefly established a settlement on the west coast of North America. Hondius' map was based on journal and eyewitness accounts of the trip and has long fueled speculation about the precise location of Drake's landing, which has not yet been firmly established by historians. Hondius is also thought to be the artist of several well-known portraits of Drake that are now in the National Portrait Gallery in London. In 1593, Hondius returned to Amsterdam, where he remained until the end of his life. In 1604, he purchased the plates of Gerard Mercator's Atlas from Mercator's grandson. Mercator's work had languished in comparison to the rival atlas, Theatrum Orbis Terrarum by Ortelius. Hondius republished Mercator's work with 36 additional maps, including several which he himself produced. Despite the addition of his own contributions, Hondius recognizing the prestige of Mercator's name, gave Mercator full credit as the author of the work, listing himself as the publisher. Hondius' new edition of Mercator revived the great cartographer's reputation and was a great success, selling out after a year. Hondius later published a second edition, as well as a pocket version called the Atlas Minor. The maps have since become known as the "Mercator/Hondius series". Between 1605 and 1610 Hondius was employed by John Speed to engrave the plates for Speed's The Theatre of the Empire of Great Britaine. Following Hondius' death in 1612, his publishing work in Amsterdam was continued by his widow and two sons, Jodocus II and Henricus. Later his family formed a partnership with Jan Jansson, whose name appears on the Atlasas co-publisher after 1633. Eventually, starting with the first 1606 edition in Latin, about 50 editions of the Atlas were released in the main European languages. In the Islamic world, the atlas was partially translated by the Turkish scholar Katip Çelebi. The series is sometimes called the 'Mercator/Hondius/Jansson' series because of Jansson's later contributions. Hondius' is also credited with a number of important cartographic innovations including the introduction of decorative map borders and contributions to the evolution of 17th century Dutch wall maps. The work of Hondius was essential to the establishment Amsterdam as the center of cartography in Europe in the 17th century. More by this mapmaker...

Captain John Smith (1580 - 1631) was an English soldier, explorer, colonial governor, Admiral of New England, author, and self-promoter. He was pivotal in the establishment of the first permanent English settlement in America (Jamestown, Virginia) and was the first Englishman to map the Chesapeake Bay, and the coast of New England. His maps of these areas, especially his mapping of the Chesapeake, were broadly influential: there are few maps of Virginia that were produced in the 17th century that do not derive from his work. His books describing the Virginia Colony were themselves important in encouraging further settlement.

Smith was born to a farming family in Lincolnshire; after his father's death, he began his military career as a mercenary, fighting with the French at war with Spain. He was intermittently a merchant and a pirate in the Mediterranean, where his travels brought him into the fight against the Ottoman Turks. He fought for the Austrian Habsburgs in Hungary, and fought for Radu Șerban in Wallachia against Ottoman vassal Ieremia Movilă. His coat of arms - featuring three Turkish heads - was itself a gruesome memento of Smith's reputedly killing and beheading of three Ottoman challengers in single-combat duels. His fortunes turned in 1602, which saw him captured and enslaved by the Crimean Tatars, captured, and sold as a slave - a condition which apparently lasted only long enough for him to escape to Muscovy, thence to take the scenic route back to England in 1604.

In 1606, Smith was sent as one of the leaders of London's Virginia Company's effort to colonize Virginia. Over the course of the next year, as some sixty percent of the settlers died of starvation and disease, Smith explored Chesapeake Bay and its vicinity, producing his seminal, wildly influential map which would be eagerly copied by mapmakers throughout the next century. Preserved on this map was also a body of water, reported to Smith by Native Americans, which he believed to be either a massive lake, or the Sea of Verrazano - in short, the Pacific. He was forced to return to England in 1609 following his injury in a gunpowder explosion in his canoe. While in England, Smith passed on a tip on this possible Pacific passage to Henry Hudson, who would gain no joy of it.

Smith did not return to Virginia. He did, however, return to America, exploring the coast of New England in 1614. (This name was his own; Smith's New England would be the first map to employ that appellation.) Smith's 1614 journey was meant to capture whales for their oil, and to find gold or copper mines. Failing these, they found instead fish and furs. It is also very likely that in his exploration of the northeastern coast, Smith was the same Sea of Verrazano that so tantalized Hudson.

A difficulty with Smith's biography is that so much of it relies entirely on his own report: and Smith does not at all appear to have been a modest man.

Learn More...