This item has been sold, but you can get on the Waitlist to be notified if another example becomes available, or purchase a digital scan.

1574 Ruscelli map of the World According to Ptolemy

PtolemaicWorld-ruscelli-1574-2

Title

1574 (undated) 7.75 x 10.5 in (19.685 x 26.67 cm)

Description

The Projection

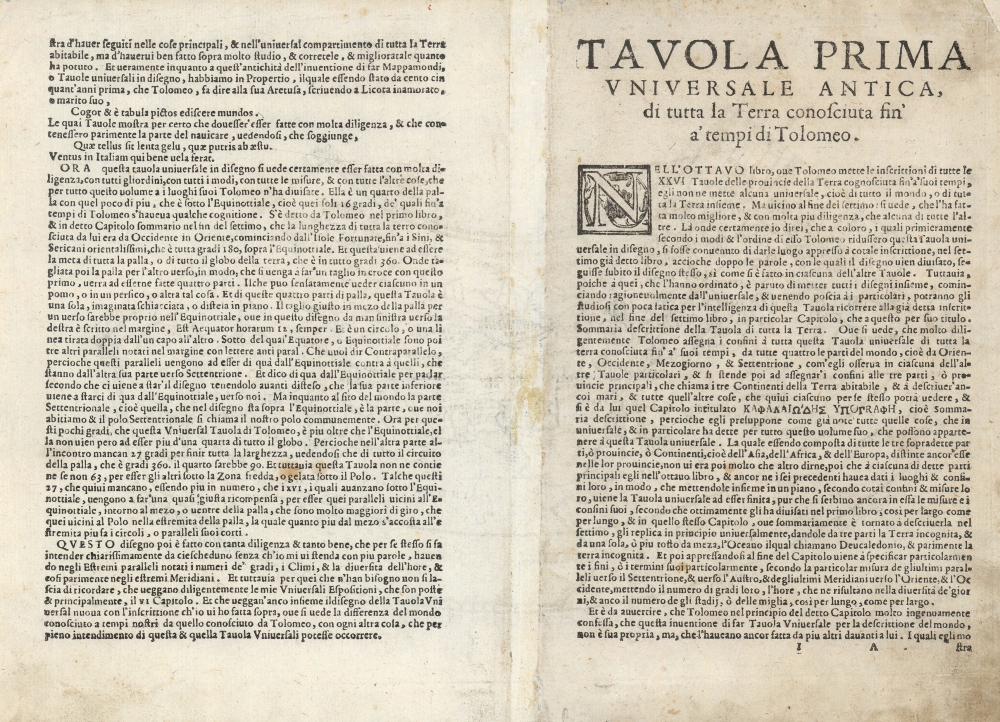

Ptolemy's work is most important in that it distinguishes between chorography - regional mapping - and geography, which was concerned with understanding and measuring the known world, and representing those measurements graphically. Ptolemy proposed two new types of projection to represent the spherical world in two dimensions. The first, conic projection, is based on a cone tangent to the Earth at the 36° parallel, showing the meridians as straight lines that tend to close towards the poles, and showing parallels as concentric arcs. The second, more complex projection modifies the conic projection by presenting the meridians as curving inwards towards the poles. The latter was the model used for the map appearing in Ruscelli's 1561-1564 edition, prior to its replacement with this plate.A Closer Look

Employing the former, conic projection, the present map is the simpler and clearer of the two and is better suited to the educational role for which it was intended. It labels Ptolemy's latitudes and longitudes at the top, bottom, and right-hand borders. Along the left-hand border are more detailed labels of the climate zones, including the hours of daylight at the solstice at given latitudes.Ptolemy's Grid

Ptolemy's great innovation was in the idea that features of the world - cities, mountains, rivers, seas, and so forth - could have their relative locations fixed by measuring the distances between them, and that these could be marked on a grid, thus providing a mathematically correct representation of the globe on a flat surface. All modern cartography developed from this understanding. Ptolemy's data reflected that available to a second-century Alexandrian: with the result that Ptolemy's work painted a picture using second century European place names, limited by that era's European exploration and knowledge of the world, and the era's limited ability to accurately measure distances. The picture of the world thus presented is necessarily distorted, despite the utility and importance of the methodology.The Map

The Ptolemaic 'world map' is a representation of only the known inhabited world, the Oikoumene. Its westernmost limit is the 'Fortunate Isles' (Fortunatae) in the Atlantic Ocean and to the east, the projection ends at China (Sinarum Situs). The map shows from 63 degrees north, to 14 degrees south: thus encompassing the British Isles as the northernmost limit of Europe, while the southern limits of the map pass far beyond those areas familiar to second-century travelers, and well into the realm of speculation and legend.The Indian Ocean and the Sinus Magnus

The Indian Ocean is presented as a massive, inland sea. Note that at the southern limits of eastern Africa, Ptolemy's 'Prassum Promont', the coastline turns sharply to the east and continues until it turns north, ultimately meeting the Asian coastline at China beyond the Malay Peninsula and 'India Beyond the Ganges.' The portion of the Indian Ocean enclosed beyond the peninsula, Ptolemy termed the Great Bay, or 'Magnus Sinus.' The Portuguese journeys around Africa proved that the land connection between China and Africa around the Indian Ocean did not exist: what, then, was the extent of the Magnus Sinus? Did land reach around it to the south from China? Was the ocean discovered by Magellan's voyage the same body of water as this? Was the mysterious coastline at the eastern limit of Ptolemy's knowledge the same as the west coast of the Americas? All European geographical thinking about the Pacific Ocean and the nature of the American discoveries began from a foundation of knowledge encapsulated in this map.Africa and The Nile

Northern Africa was nearly as well understood by Ptolemy as was Europe itself: all fell within the bounds of the Roman Empire, and after all, the Greco-Roman Ptolemy was, himself, a native of Alexandria. Beyond the great African deserts, however, lay mysteries which remained poorly illuminated well beyond the Age of Discovery. Ptolemy's sources told him of the sources of the Nile - found in the lakes of the Mountains of the Moon. This representation remained unchallenged on maps of Africa until the end of the 17th century.The Mysteries of Scythia and the East

The Indies and Africa were not the only lands draped in obscurity for classical Alexandrian scholars. Beyond the Black Sea to the north and east, Ptolemy's geography grows less and less detailed. The regions of Scythia, Serica, and the Imaum mountains were - to Ptolemy's era - the domain of little-known nomadic peoples, often reputed to be cannibals. The Persian kingdoms of Sogdiana, Bactriana, Parthia, and so on are accurately placed, but the Caspian, or Hyrcanian, Sea is shown distorted into an east-west oval which would not be corrected in European geography until the 18th century.Publication History and Census

This map was first engraved for publication in the 1574 Ziletti edition of Ruscelli's La Geographia di Claudio Tolomeo…, and it continued in use for later editions of the work. The present example conforms typographically to the 1574 edition. We see five examples of this issue of the separate map listed in institutional collections. It appears on the market from time to time.CartographerS

Claudius Ptolemy (83 - 161 AD) is considered to be the father of cartography. A native of Alexandria living at the height of the Roman Empire, Ptolemy was renowned as a student of Astronomy and Geography. His work as an astronomer, as published in his Almagest, held considerable influence over western thought until Isaac Newton. His cartographic influence remains to this day. Ptolemy was the first to introduce projection techniques and to publish an atlas, the Geographiae. Ptolemy based his geographical and historical information on the "Geographiae" of Strabo, the cartographic materials assembled by Marinus of Tyre, and contemporary accounts provided by the many traders and navigators passing through Alexandria. Ptolemy's Geographiae was a groundbreaking achievement far in advance of any known pre-existent cartography, not for any accuracy in its data, but in his method. His projection of a conic portion of the globe on a grid, and his meticulous tabulation of the known cities and geographical features of his world, allowed scholars for the first time to produce a mathematical model of the world's surface. In this, Ptolemy's work provided the foundation for all mapmaking to follow. His errors in the estimation of the size of the globe (more than twenty percent too small) resulted in Columbus's fateful expedition to India in 1492.

Ptolemy's text was lost to Western Europe in the middle ages, but survived in the Arab world and was passed along to the Greek world. Although the original text almost certainly did not include maps, the instructions contained in the text of Ptolemy's Geographiae allowed the execution of such maps. When vellum and paper books became available, manuscript examples of Ptolemy began to include maps. The earliest known manuscript Geographias survive from the fourteenth century; of Ptolemies that have come down to us today are based upon the manuscript editions produced in the mid 15th century by Donnus Nicolaus Germanus, who provided the basis for all but one of the printed fifteenth century editions of the work. More by this mapmaker...

Girolamo Ruscelli (1500 - 1566) was an Italian polymath, humanist, editor, and cartographer active in Venice during the early 16th century. Born in Viterbo, Ruscelli lived in Aquileia, Padua, Rome and Naples before relocating to Venice, where he spent much of his life. Cartographically, Ruscelli is best known for his important revision of Ptolemy's Geographia, which was published posthumously in 1574. Ruscelli, basing his work on Gastaldi's 1548 expansion of Ptolemy, added some 37 new "Ptolemaic" maps to his Italian translation of the Geographia. Ruscelli is also listed as the editor to such important works as Boccaccio's Decameron, Petrarch's verse, Ariosto's Orlando Furioso, and various other works. In addition to his well-known cartographic work many scholars associate Ruscelli with Alexius Pedemontanus, author of the popular De' Secreti del R. D. Alessio Piemontese. This well-known work, or "Book of Secrets" was a compilation of scientific and quasi-scientific medical recipes, household advice, and technical commentary on a range of topics that included metallurgy, alchemy, dyeing, perfume making. Ruscelli, as Alexius, founded a "Academy of Secrets," a group of noblemen and humanists dedicated to unearthing "forbidden" scientific knowledge. This was the first known experimental scientific society and was later imitated by a number of other groups throughout Europe, including the Accademia dei Secreti of Naples. Learn More...

Source

- 1561 La Geographia di Claudio Tolomeo Alessandrino, Italian. Venice, Vincenzo Valgrisi.

- 1562 Geographia Cl. Ptolemaei Alexandrini, Latin. Venice, Vincenzo Valgrisi.

- 1564 La Geographia di Claudio Tolomeo Alessandrino, Italian. Venice, Giordano Ziletti.

- 1564 Geographia Cl. Ptolemaei Alexandrini, Latin. Venice, Giordano Ziletti.

- 1574 La Geographia di Claudio Tolomeo Alessandrino, Italian. Venice, Giordano Ziletti.

- 1598 Geographia di Claudio Tolomeo Alessandrino, Italian. Venice, heirs of Melchoir Sessa.

- 1599 Geographia di Claudio Tolomeo Alessandrino, Italian. Venice, heirs of Melchoir Sessa.