This item below is out of stock, but another example (left) is available. To view the available item, click "Details."

Details

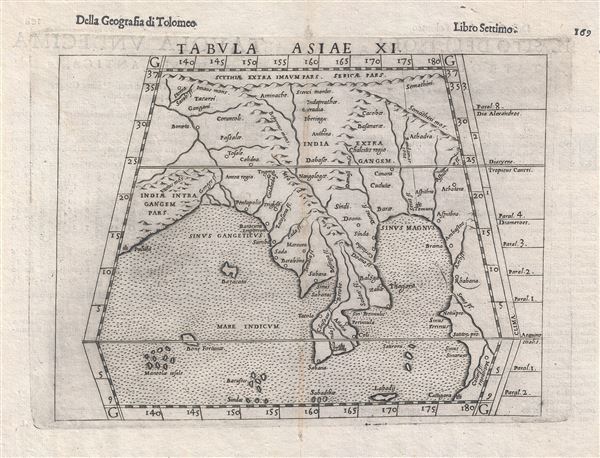

1561 Ruscelli/ Ptolemy Map of Southeast Asia

1561 (undated) $350.00

1574 Ruscelli and Ptolemy Map of Southeast Asia

TabulaAsiaeXI-ruscelli-1574

Title

1574 (undated) 8 x 10.5 in (20.32 x 26.67 cm) 1 : 32000000

Description

Although somewhat difficult to understand in the context of modern geography, this map rangers from the Ganges River in India east to cover all of Thailand, Burma, Vietnam and the China Sea, it extends southward to the tip of the Malay Peninsula, and north to the Himalayas. The Ganges can be clearly identified. To the east of this river the Kingdom of Anrea Regio appears to correspond to Burma. Anyone admiring the golden monuments of modern Burma would have no trouble understanding the name, Anrea Regio, which roughly translates to 'Kingdom of Gold.' Following the shore southwards we come to a gulf or bay identified as Sinus Sabarac, most likely the modern day Gulf of Martaban. Across the narrow isthmus, another gulf, the Sinus Perimulic, would therefore be the Gulf of Thailand. In Malaya itself the Chirsonaie Fleuve, no doubt refers to Cheronesus, an archaic name for the region. The city of Sabana is located roughly where Singapore is today though some speculate that the island that it rests on could only be Sumatra. The mountain range running down the middle of the region correctly corresponds to the mountainous divide separating modern day Thailand from Burma. Ptolemy refers to this region as

a habitat of tigers and elephants . . . lions and robbers and wild men who live in caves, having skins like the hippopotamus, who are able to hurl darts with ease.Between India and Malaya the Island of Bazacata most likely represents the Nicobar Islands. Ptolemy comments in his Geographica that the people of this island do not wear clothing; a convention commonly associated with the Nicobar Islands and reported by numerous travelers including Marco Polo, as well as Arab and Chinese navigators. The islands further south, Bone Fortune, Maneolae, and others, were believed to be highly magnetic such that the nails would be pulled from passing ships, causing them to sink while the hapless crews were devoured by the indigenous anthropophagi.

This map's most intriguing element is the southward extension of land running along the eastern edge of the map and extending beyond the border. This landmass reflects speculation, inspired by Ptolemy, that the Indian Ocean was landlocked. It was believed that this landmass extended far southwards before turning westward and connecting with eastern Africa. Though the exploits of Vasco de Gama and Magellan had proven that the Indian Ocean was not fully land locked, it was believed that a large tract of land, possibly even America, attached to Asia west of Malaya or the Cheronesus. Thus the 'Great Promontory' or 'Dragon's Tail' that appeared on many maps of this region well into the 16th century. The City of Cattigara, located here in the bottom right corner of the map, is cited by Ptolemy as southernmost known point. There has been considerable debate about the true location of Cattigara, certainly Magellan and the other great navigators failed to identify it, with some attaching the name to Hanoi or South China and others placing it on the shores of South America. Be as it may, the Ptolemaic model retained a great deal of influence well into the 16th century until Portuguese and Dutch navigators more fully explored the region.

A fine, collectable, and early piece essential for any serious collection focused on the cartographic emergence of Southeast Asia in European maps. Published in Girolamo Ruscelli's Italian 1574 edition of the Geografia di Tolomeo.

Cartographer

Girolamo Ruscelli (1500 - 1566) was an Italian polymath, humanist, editor, and cartographer active in Venice during the early 16th century. Born in Viterbo, Ruscelli lived in Aquileia, Padua, Rome and Naples before relocating to Venice, where he spent much of his life. Cartographically, Ruscelli is best known for his important revision of Ptolemy's Geographia, which was published posthumously in 1574. Ruscelli, basing his work on Gastaldi's 1548 expansion of Ptolemy, added some 37 new "Ptolemaic" maps to his Italian translation of the Geographia. Ruscelli is also listed as the editor to such important works as Boccaccio's Decameron, Petrarch's verse, Ariosto's Orlando Furioso, and various other works. In addition to his well-known cartographic work many scholars associate Ruscelli with Alexius Pedemontanus, author of the popular De' Secreti del R. D. Alessio Piemontese. This well-known work, or "Book of Secrets" was a compilation of scientific and quasi-scientific medical recipes, household advice, and technical commentary on a range of topics that included metallurgy, alchemy, dyeing, perfume making. Ruscelli, as Alexius, founded a "Academy of Secrets," a group of noblemen and humanists dedicated to unearthing "forbidden" scientific knowledge. This was the first known experimental scientific society and was later imitated by a number of other groups throughout Europe, including the Accademia dei Secreti of Naples. More by this mapmaker...

Source

- 1561 La Geographia di Claudio Tolomeo Alessandrino, Italian. Venice, Vincenzo Valgrisi.

- 1562 Geographia Cl. Ptolemaei Alexandrini, Latin. Venice, Vincenzo Valgrisi.

- 1564 La Geographia di Claudio Tolomeo Alessandrino, Italian. Venice, Giordano Ziletti.

- 1564 Geographia Cl. Ptolemaei Alexandrini, Latin. Venice, Giordano Ziletti.

- 1574 La Geographia di Claudio Tolomeo Alessandrino, Italian. Venice, Giordano Ziletti.

- 1598 Geographia di Claudio Tolomeo Alessandrino, Italian. Venice, heirs of Melchoir Sessa.

- 1599 Geographia di Claudio Tolomeo Alessandrino, Italian. Venice, heirs of Melchoir Sessa.