This item below is out of stock, but another example (left) is available. To view the available item, click "Details."

Details

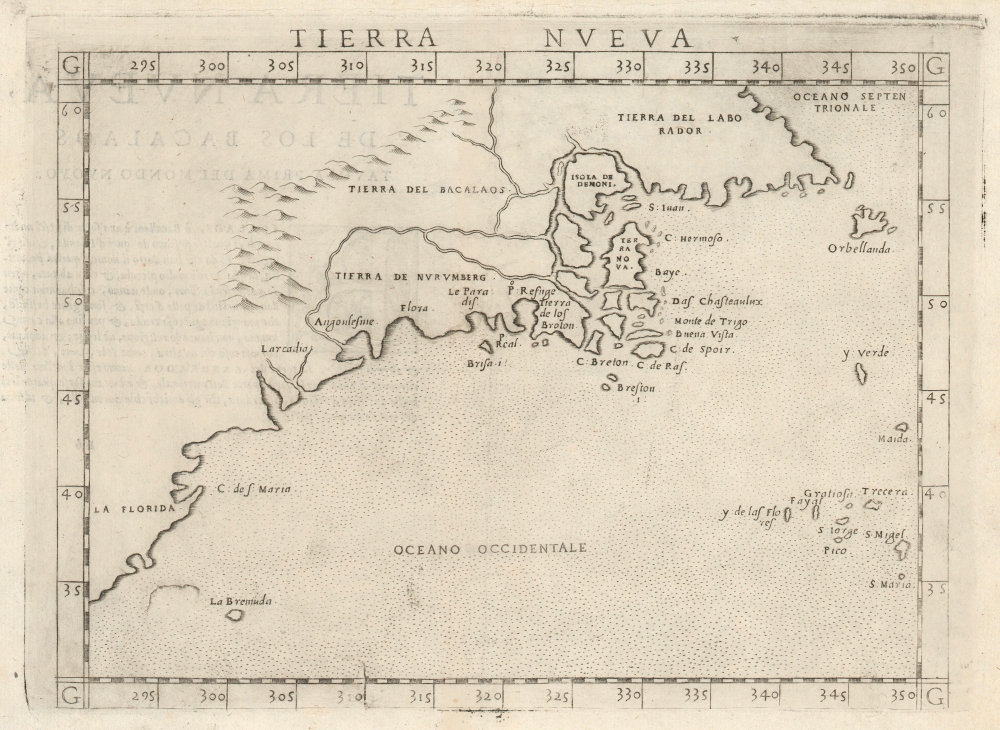

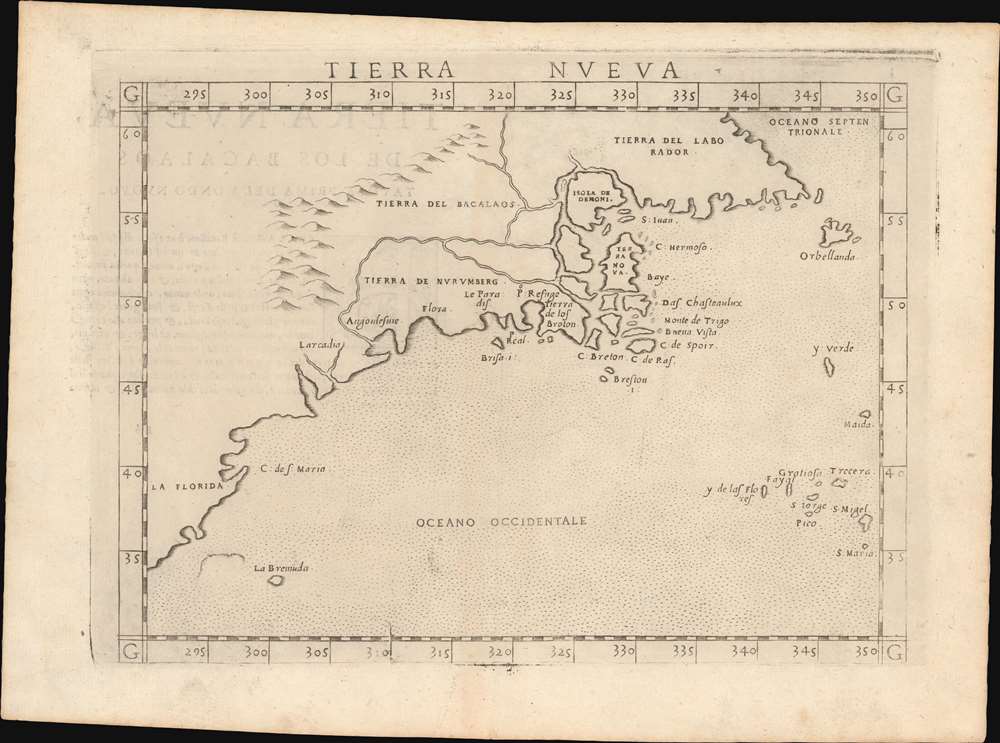

1574 Ruscelli Map of New England and the Maritimes (Norumbega)

$2,000.00

1574 Ruscelli Map of New England and the Maritimes (Norumbega)

TierraNveva-ruscelli-1574

Title

1574 (undated) 7.5 x 10.5 in (19.05 x 26.67 cm) 1 : 21000000

Description

Reconciling the Toponomy

Cartographically this map offers a fascinating look at early cartographer's attempts to reconcile the discoveries of Giovanni Verrazzano with those of Jacques Cartier. Although there is some scholarly disagreement regarding the modern equivalent of the coastal toponymy, the general consensus is as follows, from south to north. Larcadia, named by Verrazzano because of its forested beauty, is now assumed to have been somewhere near Kitty Hawk. In the subsequent decades Larcadia was moved further and further north until it came to refer to the coasts of Maine and the Canadian Maritimes. Angoulesme was the place name Verrazzano gave to New York Harbor (although Andre Thevet, writing in 1550, also takes credit for the term). Flora is most likely the south coast of Long Island. Brisa is almost certainly Block Island. Pt. Refuge is Narragansett Bay. The Chesapeake Bay, Delaware Bay, Cape Cod, and Boston Harbor are notably absent, as Verrazzano was forced too far out to sea for fear of reefs to see their entrances.Verrazzano and Cartier

Here it gets even more confusing due to the fact that this is where the discoveries of Giovanni Verrazzano and Jacques Cartier almost but not quite meet. Verrazzano was sailing north from the Carolina coast while Cartier sailed south from Labrador into the Gulf of the St. Lawrence. Given that Cartier never sailed south of Prince Edward Island and Verrazzano barely skirted the southern tip of Nova Scotia, neither fully explored this region. But, we can make some guesses as to the place names. C. Breton is possibly Cape Breton Island or somewhere else in the eastern Maritimes. The mass of islands and rivers, with names like Isola de Dimoni (Island of Demons) and Terra Nova, is mostly likely a primitive depiction of the coast of Maine around the Penobscot River, Nova Scotia, Newfoundland, the Gulf of St. Lawrence, and Labrador. Labrador, here thus labeled as 'Tierra del Labrorador', is vaguely recognizable as it juts out into the sea. 'Orbellanda', a term derived from Arthurian legend, is similarly recognizable as Newfoundland. Both are clearly based upon Cartier's explorations.Ramusio's Prescient River System

The river system extending inland both from the speculative St. Lawrence Bay (around Isola de Demoni and Terra Nova) and from Angoulesme (New York Harbor), thus joining the Hudson with the St. Lawrence, and at the same time embracing the mysterious land of 'Tierra de Nurumbeg', is a curious innovation unique to this map. The idea evolved from a more specific 1554 map of the confusing region between Angoulesme and Labrador by still another Venetian, Giovanni Battista Ramusio. Although his reasoning is unclear, Ramusio doubtless extracted his data from the second voyage of Cartier. Although incorrect at the time, Ramusio was remarkably prescient regarding the practicality of such a connection. Today a network of canals, including the Champlain Canal and the Chambly Canal, do indeed connect the two rivers, creating an important navigable corridor between the St. Lawrence and the Hudson.Nurembega

'Tierra de Nurumbeg' itself is the fascinating highlight of this map. This mysterious land appeared on many early maps of New England starting with Verrazano's 1529 manuscript map of America. He used the term, Oranbega, which in Algonquin means something on the order of 'lull in the river'. The first detailed reference to Nurumbeg, or as it is more commonly spelled Norumbega, appeared in the 1542 journals of the French navigator Jean Fonteneau dit Alfonse de Saintonge, or Jean Allefonsce for short. Allefonsce was a well-respected navigator who, in conjunction with the French nobleman Jean-François de la Roque de Roberval's attempt to colonize the region, skirted the coast south of Newfoundland in 1542. He discovered and apparently sailed some distance up the Penobscot River, encountering a fur rich American Indian city named Norumbega - somewhere near modern-day Bangor, Maine.The river is more than 40 leagues wide at its entrance and retains its width some thirty or forty leagues. It is full of Islands, which stretch some ten or twelve leagues into the sea. ... Fifteen leagues within this river there is a town called Norombega, with clever inhabitants, who trade in furs of all sorts; the town folk are dressed in furs, wearing sable. ... The people use many words which sound like Latin. They worship the sun. They are tall and handsome in form. The land of Norombega lies high and is well situated.Though Roberval's colony lasted only two years, Andre Thevet, writing in 1550, records encountering a French trading fort at the site of Norumbega.

A few years later in 1562, an English slave ship wrecked in the Gulf of Mexico. David Ingram, one of the survivors, claimed to have trekked overland from the Gulf Coast to Nova Scotia where he was rescued by a passing French ship. Possibly inspired by Mexican legends of El Dorado, Cibola, and other lost cities, Ingram returned to Europe to regale his drinking companions with boasts of a fabulous city rich in pearls and built upon pillars of crystal, silver, and gold. The idea caught on in the European popular imagination and expeditions were sent to search for the city - including that of Samuel de Champlain.

The legend of Norumbega thus seems to have transitioned from Allefonsce's most likely factual description of a lively American Indian fur trading center, to Thevet's French trading fort, to Ingram's fabulous paradise dripping in wealth. Allefonsce's description of the American Indians he encountered in Norumbega corresponds well those of Hudson, who also met a tall well-proportioned people. Sadly only a few years later many of these tribes began to die off at extraordinary rates (over 90% of the population perished) due to horrifying outbreaks of smallpox and other diseases carried by the unwitting European explorers. It seems reasonable that Allefonsce may have stumbled upon a periodic or semi-permanent indigenous fur trading center on the Penobscot. It also seems reasonable that French colonists may have set up their fur trading post at the same site, for it was fur, not gold that was the real wealth of New England and Norumbega. Alas, it was Ingram's fictitious account, which, though wholly the product of a drunken sailor's imagination, produced the most enduring image of Norumbega.

Centuries later, in the 19th century, some armchair theorists, most notably Eben Norton Horsford, postulated based upon Allefonsce's descriptions and their own questionable research that Norumbega was a term derived from Norvegr (Norwegian), and that it was in fact a Viking city that Allefonsce discovered. We find this highly unlikely; however, Horsford's work inextricably linked Norumbega with speculations relating to Viking settlements in North America.

Publication History and Census

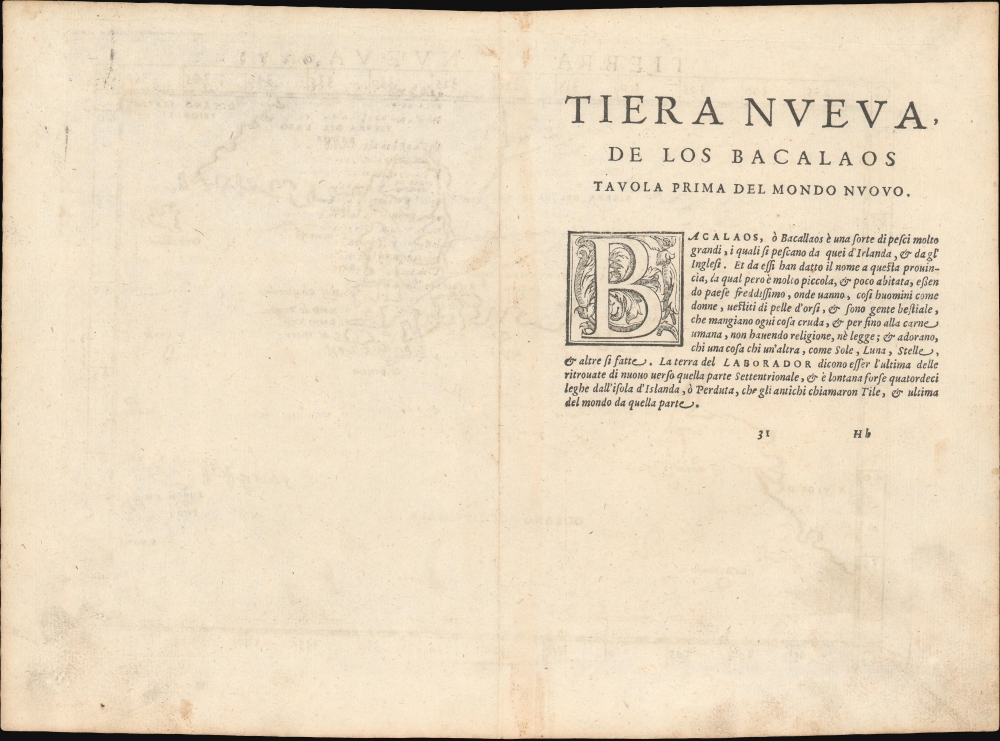

This map was first published by Girolamo Ruscelli for this 1561 first edition of the Geography of Claudius Ptolemy, La Geografia di Claudio Tolomeo. It was engraved by Giulio and Livio Sanuto. It was reissued in various editions of the work, without changes, until 1564. The first state can be recognized by a pressmark that runs off the top of the page. The pressmark was retooled in 1574 with the second state of the plate (current example). In addition, crosshatching was added to the graduation marks. A third state appeared in 1598 with several significant geographical revisions, including the addition of a sea monster, a ship, and the placenames 'Virginia' and 'Nova Francia'. This map comes to the market from time to time and is well represented in institutional collections as a staple of early North America cartography.CartographerS

Girolamo Ruscelli (1500 - 1566) was an Italian polymath, humanist, editor, and cartographer active in Venice during the early 16th century. Born in Viterbo, Ruscelli lived in Aquileia, Padua, Rome and Naples before relocating to Venice, where he spent much of his life. Cartographically, Ruscelli is best known for his important revision of Ptolemy's Geographia, which was published posthumously in 1574. Ruscelli, basing his work on Gastaldi's 1548 expansion of Ptolemy, added some 37 new "Ptolemaic" maps to his Italian translation of the Geographia. Ruscelli is also listed as the editor to such important works as Boccaccio's Decameron, Petrarch's verse, Ariosto's Orlando Furioso, and various other works. In addition to his well-known cartographic work many scholars associate Ruscelli with Alexius Pedemontanus, author of the popular De' Secreti del R. D. Alessio Piemontese. This well-known work, or "Book of Secrets" was a compilation of scientific and quasi-scientific medical recipes, household advice, and technical commentary on a range of topics that included metallurgy, alchemy, dyeing, perfume making. Ruscelli, as Alexius, founded a "Academy of Secrets," a group of noblemen and humanists dedicated to unearthing "forbidden" scientific knowledge. This was the first known experimental scientific society and was later imitated by a number of other groups throughout Europe, including the Accademia dei Secreti of Naples. More by this mapmaker...

Livio Sanuto (1520 – 1576) was a Venetian cartographer and scientific instrument maker produced, with his engraver brother, Giulio (fl. 1540-1588) – an array of some of the most important geographical works produced in Venice during the second half of the sixteenth century. These included a 27-inch globe and the 1588 12-sheet atlas, Geografia della Africa. Among Livio and Giulio's works were some, if not all of the maps prepared for Ruscelli's 1561 Ptolemy. Learn More...

Giulio Sanuto (fl. 1540 – 1580) was a Venetian engraver. He was born the illegitimate son of Cavaliere Francesco di Angelo Sanuto; With his brother, the cartographer and scientific instrument maker Livio Sanuto (1520 – 1576) he produced an array of some of the most important geographical works produced in Venice during the second half of the sixteenth century. These included a 27-inch globe and the 1588 12-sheet atlas, Geografia della Africa. Giulio's career is singluar among Venice's engraves in that it appears to have been equally based on artistic, figurative work as well as his cartographic works. Giulio is more broadly known for a small but sought-after selection of decorative engravings; no more than twelve of these can be attributed confidently to him, including the monumental Apollo and Marsyas, measuring over 1.30 meters wide. Whilst Sanuto's engravings were generally based upon the designs of other artists, his work was both ambitious and grand, and he often signed these works. Learn More...

Source

- 1561 La Geographia di Claudio Tolomeo Alessandrino, Italian. Venice, Vincenzo Valgrisi.

- 1562 Geographia Cl. Ptolemaei Alexandrini, Latin. Venice, Vincenzo Valgrisi.

- 1564 La Geographia di Claudio Tolomeo Alessandrino, Italian. Venice, Giordano Ziletti.

- 1564 Geographia Cl. Ptolemaei Alexandrini, Latin. Venice, Giordano Ziletti.

- 1574 La Geographia di Claudio Tolomeo Alessandrino, Italian. Venice, Giordano Ziletti.

- 1598 Geographia di Claudio Tolomeo Alessandrino, Italian. Venice, heirs of Melchoir Sessa.

- 1599 Geographia di Claudio Tolomeo Alessandrino, Italian. Venice, heirs of Melchoir Sessa.