This item has been sold, but you can get on the Waitlist to be notified if another example becomes available, or purchase a digital scan.

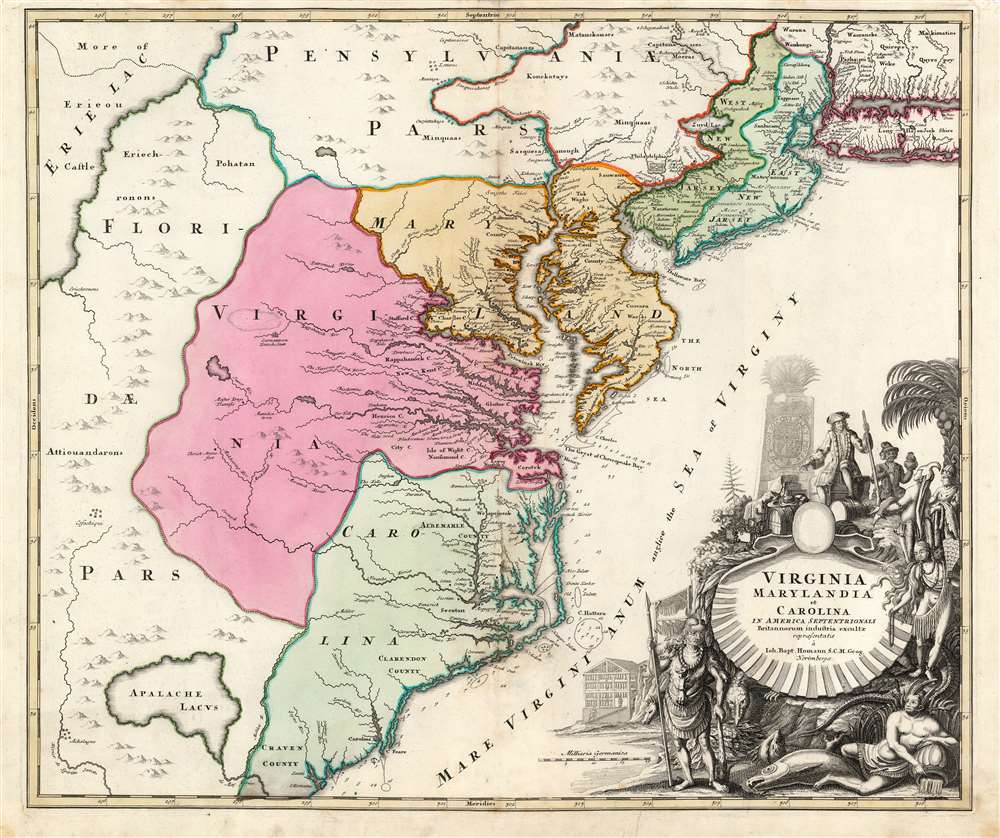

1714 Homann Map of Carolina, Virginia, Maryland and New Jersey

VirginiaMarylandiaCarolina-homann-1715-5

Title

1715 (undated) 19.75 x 23.5 in (50.165 x 59.69 cm) 1 : 2100000

Description

Spotswood's Plan - Settling Germans in Virginia

While serving as Virginia Lieutenant Governor and de facto governor, Spotswood (1676 - 1740) received numerous land grants in Virginia's interior - then a little-known mountainous region. The intent of the grants was to create a buffer zone against French incursion from the west. Aware of potential mineral resources, Spotswood conceived a plan to entice German miners and ironworkers - then widely recognized as the best in Europe - to settle there. Such was not without precedent, as earlier maps and other evidence suggest there were already German settlers in the Shenandoah Valley, such as 'Miester Krugs Plantasie', likely emigres from the German settlements in Pennsylvania just to the north.German Settlements in Virginia

Spotswood began advertising in Germany for potential immigrants and contracted Johann Baptist Homann to make a map highlighting his vision. Here, three towns of potential interest to the German immigrant appear for the first time: 'Germantown Teutsche Statt' (Germanna) on the Rapidan River, Fort Christanna (Christ Anna Fort) on the Makharing River, and 'Miester Krugs Plantasie' on the James River. Of Master Krug's Plantation, little or nothing is known, but it is believed to pre-date Spotswood's grants. The other two settlements, Germanna and Fort Christanna, are significant. Germanna is the site where most of Spotswood's miners would eventually settle. It is also where Spotswood established his ironworks and later settled himself, constructing an enormous manor house.Fort Christanna, further south, was built as a bulwark against the French and French-aligned American Indian groups such as the Tuscarora. Christanna also acted as the headquarters of the Virginia Indian Company, a joint-stock venture founded in 1714 with the intention of trading with indigenous nations.

Knights of the Golden Horseshoe

Little has been said about the mapping of Lake Erie occupying the northwest quadrant. By 1715, the general outline and location of all five Great Lakes were known - but their proportions and latitudinal level were still debated. The influential 1685 Jean Baptiste Louis Franquelin manuscript map places Lake Erie's southernmost shore roughly level with the northern part of the Chesapeake Bay - as shown here. Based upon the best cartography of the time, it was logical to assume one might travel northwest from Virginia only a short distance before reaching Erie. In 1716, Spotswood launched his Knights of the Golden Horseshoe Expedition, in which a band of some 50 prominent Virginians set forth from Germanna to explore a potential route to Erie. This was a gentlemanly expedition, lacking the horrors commonly associated with exploration. They are said to have stopped frequently to enjoy the ample provisions of wine and spirits, not a single explorer was lost, and meetings with American Indian nations were peaceful. They crossed the Blue Ridge Mountains and entered the Shenandoah Valley, claiming it in the name of King George I. They did not reach Lake Erie, but believed they had discovered the route. In return, Spotswood gave expedition members commemorative tokens shaped like a golden horseshoe.Lake Erie?

Spotswood wrote that the expedition aimed to discover a route to Lake Erie, which he believed to be close and accessible. On this map, it is separated from Germanna by a narrow range of mountains (the Blue Ridge?), beyond which rivers flow directly into the Lake. This intervening territory he attaches to 'Florida'. The occupants of this region were mostly American Indian nations loosely allied to French Louisiana. Whether Homann is here using 'Spanish Florida' to undermine French claims OR referencing 'French Florida' claims dating to the 16th century is unclear. Either way, discovering such a route would certainly make settlement more appealing, giving access to more markets and trade, as well as thwarting the growing French influence. Spotswood later sought sanction and funding from King George I to make a second expedition, establish a trade route, and build an outpost on Lake Erie, but permission was never granted.New Mapping Meets Old

Although Homann's remarkable representation of Spotswood's plan is extraordinarily up-to-date, considering that Fort Christanna was founded around the same year this map was initially published, the remainder of the map embraces several common misconceptions and cartographic inaccuracies. Probably the most notable is his inclusion of Apalache Lacus. This lake, intended as the source of the May River, appeared on maps of this region beginning with the 1591 Le Moyne-De Bry map. Le Moyne correctly mapped the river turning south into central Florida, but later cartographers, particularly Mercator/Hondius in 1606, incorrectly mapped the lake to the northwest, in western Carolina. This is likely the result of an erroneous conflation of the May and Savannah Rivers. The apocryphal lake remained on maps well into the mid-18th century before exploration and settlement disproved it.More on the Map

Homann offers a wealth of detail along the Atlantic coast, where most of the European colonization efforts were focused. Countless towns and cities are identified from Long Island south to Craven County, Carolina. New York City is mapped on the southern tip of Manhattan Island but is not specifically labeled. New Jersey is divided into the colonial provinces of East New Jersey and West New Jersey. Curiously, Homann maps a large inland lake, 'Zuyd Lac,' straddling the New Jersey - Pennsylvania border. This is undoubtedly an early interpretation of the natural widening of the Delaware River at the Delaware Water Gap. Heading south along the Delaware River, Philadelphia is identified and beautifully rendered as a grid embraced in four quadrants. Both the Delaware Bay and the Chesapeake Bay are engraved in full and include submarine features and depth soundings. In Virginia and Carolina, the river systems are surprisingly well-mapped, and a primitive county structure is beginning to emerge. The early Virginia counties of Rappahannock, Henrico, City, Isle of Wright, Nansemond, Northumberland, Middlesex, Gloster, and Corotvk are noted. Similarly, in Carolina, a number of counties are named, most of which refer to the Lords Proprietors, including Albemarle, Clarenden, and Craven. Cape Fear, Cape Lookout, and Cape Hatteras are noted, and a number of anchorages, reefs, and depth soundings appear.The Dramatic Cartouche

The lower right is occupied by a fabulous decorative title cartouche. Centered on an enormous scallop shell bearing the map's title, the cartouche features American Indians trading with a Spotswood. The region's wealth is expressed by an abundance of fish, game, and other trade products. Curling behind the scallop shell is a gigantic alligator styled to resemble a medieval dragon.Publication History and Census

This map was published by J.B. Homann both as a separate issue and in his Atlas Novus. Unfortunately, this map has no definitive publication date, although most date the first issue to about 1715. This would postdate the 1714 first wave of German immigrants under Spotswood's plan but pre-date the second 1717 wave. None of the locations discovered by the 1716 Knights of the Golden Horseshoe Expedition are named, suggesting it pre-dated that expedition; thus, 1715 is likely correct. Also, this example lacks the Imperial 'Cum Privilegio,' which identifies second-state examples of the map, c. 1730. The plates for the map wore out quickly, so most later examples exhibit a weak impression. The strong impression here suggests an early strike off the plate. This map appeared in various Homann atlases from about 1715 to 1730.Cartographer

Johann Baptist Homann (March 20, 1664 - July 1, 1724) was the most prominent and prolific map publisher of the 18th century. Homann was born in Oberkammlach, a small town near Kammlach, Bavaria, Germany. As a young man, Homann studied in a Jesuit school and nursed ambitions of becoming a Dominican priest. Nonetheless, he converted to Protestantism in 1687, when he was 23. It is not clear where he mastered engraving, but we believe it may have been in Amsterdam. Homann's earliest work we have identified is about 1689, and already exhibits a high degree of mastery. Around 1691, Homann moved to Nuremberg and registered as a notary. By this time, he was already making maps, and very good ones at that. He produced a map of the environs of Nürnberg in 1691/92, which suggests he was already a master engraver. Around 1693, Homann briefly relocated to Vienna, where he lived and studied printing and copper plate engraving until 1695. Until 1702, he worked in Nuremberg in the map trade under Jacob von Sandrart (1630 - 1708) and then David Funck (1642 - 1709). Afterward, he returned to Nuremberg, where, in 1702, he founded the commercial publishing firm that would bear his name. In the next five years, Homann produced hundreds of maps and developed a distinctive style characterized by heavy, detailed engraving, elaborate allegorical cartouche work, and vivid hand color. Due to the lower cost of printing in Germany, the Homann firm could undercut the dominant French and Dutch publishing houses while matching their diversity and quality. Despite copious output, Homann did not release his first major atlas until the 33-map Neuer Atlas of 1707, followed by a 60-map edition of 1710. By 1715, Homann's rising star caught the attention of the Holy Roman Emperor Charles VI, who appointed him Imperial Cartographer. In the same year, he was also appointed a member of the Royal Academy of Sciences in Berlin. Homann's prestigious title came with several significant advantages, including access to the most up-to-date cartographic information as well as the 'Privilege'. The Privilege was a type of early copyright offered to very few by the Holy Roman Emperor. Though less sophisticated than modern copyright legislation, the Privilege offered limited protection for several years. Most all J. B. Homann maps printed between 1715 and 1730 bear the inscription 'Cum Priviligio' or some variation. Following Homann's death in 1724, the firm's map plates and management passed to his son, Johann Christoph Homann (1703 - 1730). J. C. Homann, perhaps realizing that he would not long survive his father, stipulated in his will that the company would be inherited by his two head managers, Johann Georg Ebersberger (1695 - 1760) and Johann Michael Franz (1700 - 1761), and that it would publish only under the name 'Homann Heirs'. This designation, in various forms (Homannsche Heirs, Heritiers de Homann, Lat Homannianos Herod, Homannschen Erben, etc.) appears on maps from about 1731 onwards. The firm continued to publish maps in ever-diminishing quantities until the death of its last owner, Christoph Franz Fembo (1781 - 1848). More by this mapmaker...