This item has been sold, but you can get on the Waitlist to be notified if another example becomes available, or purchase a digital scan.

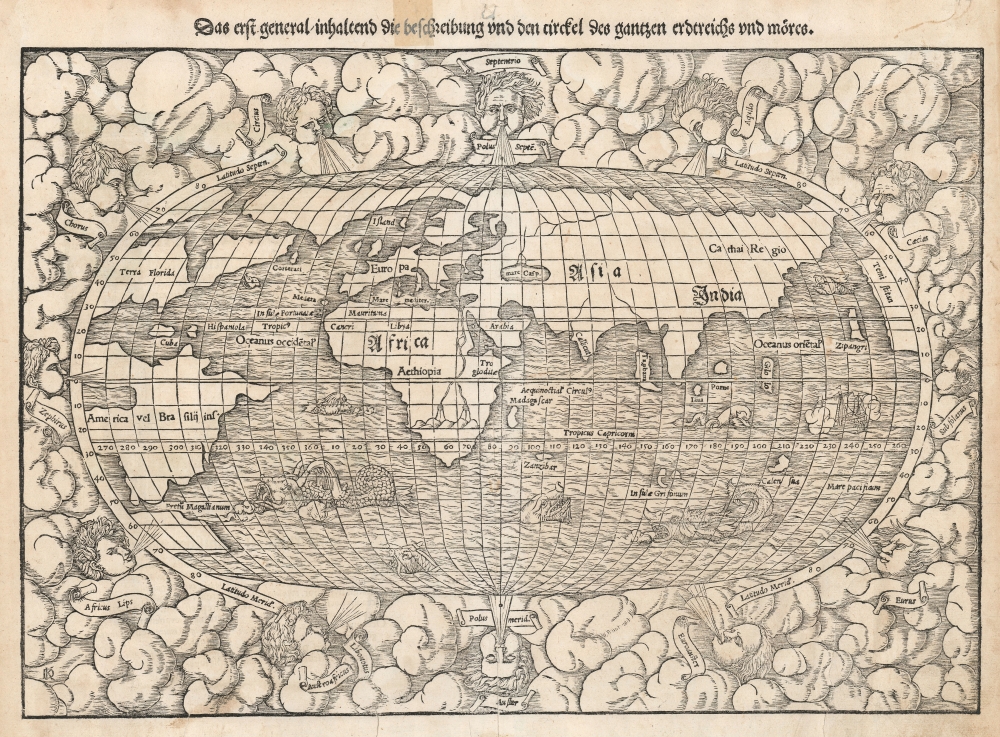

1550 Münster Map of the World

World-munster-1550-4

Title

1550 (undated) 10.5 x 14.75 in (26.67 x 37.465 cm) 1 : 120000000

Description

An Impressive Array of Firsts

Along with Münster's map of America, this is the first map to name the Pacific Ocean and the Straits of Magellan. It ranks among the earliest acquirable maps to show and name Japan (Zipangri, here just off the American coast.). In conjunction with Munster's concurrently-published map of Asia, this is the first map to show Asia in a form shorn of Ptolemaic elements: there is no 'Dragon's Tail' or other element retained from Ptolemy's land bridge connecting Africa and China, and it is the first generally acquirable world map to hint at the existence of the East Indies. As distinct from the Ptolemaic maps of the late 15th and early 16th century, the island 'Taprobana' is shown not as Sri Lanka, but as Sumatra.Africa

Likewise, this is one of the earliest acquirable world maps to show the continent of Africa in recognizable form. Madagascar appears in roughly the correct location. Oddly, Zanzibar appears as an island much farther out from land than is accurate - perhaps underscoring its rising significance. Africa's interior nonetheless retains the Ptolemaic geography for the course of the Nile, and its sources in the Mountains of the Moon.A Circumnavigable Globe

More to the point, this is the first generally accessible world map to show an entirely circumnavigable globe. This map presents a world fully accessible to mariners, via the Straits of Magellan, the optimistically-sized Pacific Ocean, and the unobstructed Indian Ocean. This notion would have been new to Münster's readers, even thirty years after Magellan sailed.Speculative Geography in America

There being vast gaps in European scholars’ knowledge of the Americas, Münster and any other geographers of his era had to fill in with speculation - leading to a wealth of unusual features. The wedge-like bay bisecting North America was derived from interpretations of Verrazano’s observations during his 1524 voyage. This so-called 'Sea of Verrazano' would also appear on Münster’s map of America. The northern parts of the world betray gaps in European knowledge: the part of Europe associated with Scandinavia extends far to the west, absorbing Greenland. In North America, the Florida peninsula is just recognizable, although the entire region west of Verrazano's Sea is identified as 'Terra Florida.' The northeastern coast is marked only with an island named 'Corterati', probably a reference to Newfoundland after the Corte Reals. The Caribbean is represented by the two principal islands of Cuba and Hispaniola.Adding to the Cosmographia

From its first printings in 1544, Münster's Cosmographia was notable for maps and views depicting their subjects for the first time in print. In subsequent editions, Münster labored to build the work by ordering improved city views and additional decorative woodcuts. 1550 saw the addition of many maps and views to the body of the work. In the case of the present map, Münster had artist David Kandel dispense with some of the text of the 1540 world map, while adding decorative engraving: a sailing ship and eight sea monsters (the 1540 had only two!) Also, Kandel's woodcut improved on the composition of the original by having all twelve wind-heads placed in the cloud border around the map (the artist for the 1540 had run out of room, so the east and west winds appeared within the oval of the map itself.) Münster's spur to improve the images in Cosmographia was the 1548 publication of Johannes Stumpf's magnificently illustrated history of Switzerland, whose woodcut maps and views outstripped those in Cosmographia both in quality and number. Münster knew he had to improve, and commissioned many of the woodcuts that would make his work so popular.Publication History and Census

The first iteration of this map appeared in Münster’s 1540 edition of Ptolemy's Geographia, appearing in all but the 1552 editions of that work as well as the first, German editions of Münster's Cosmographia. In 1550, the woodblock for the map was re-cut by formschneider David Kandel (his monogram DK appears in the lower left.) This second block appeared first in the German edition of 1550 and remained in use until 1578. The subsequent editions of Cosmographia employed entirely new woodcuts, based on the then-state-of-the-art maps of Ortelius. This specific example corresponds typographically to 1550 German edition of the book. Despite map and Cosmographia being otherwise well represented in institutional collections in their various editions; we see no examples of this first issue of the 1550 listed separately in OCLC.CartographerS

Sebastian Münster (January 20, 1488 - May 26, 1552), was a German cartographer, cosmographer, Hebrew scholar and humanist. He was born at Ingelheim near Mainz, the son of Andreas Munster. He completed his studies at the Eberhard-Karls-Universität Tübingen in 1518, after which he was appointed to the University of Basel in 1527. As Professor of Hebrew, he edited the Hebrew Bible, accompanied by a Latin translation. In 1540 he published a Latin edition of Ptolemy's Geographia, which presented the ancient cartographer's 2nd century geographical data supplemented systematically with maps of the modern world. This was followed by what can be considered his principal work, the Cosmographia. First issued in 1544, this was the earliest German description of the modern world. It would become the go-to book for any literate layperson who wished to know about anywhere that was further than a day's journey from home. In preparation for his work on Cosmographia, Münster reached out to humanists around Europe and especially within the Holy Roman Empire, enlisting colleagues to provide him with up-to-date maps and views of their countries and cities, with the result that the book contains a disproportionate number of maps providing the first modern depictions of the areas they depict. Münster, as a religious man, was not producing a travel guide. Just as his work in ancient languages was intended to provide his students with as direct a connection as possible to scriptural revelation, his object in producing Cosmographia was to provide the reader with a description of all of creation: a further means of gaining revelation. The book, unsurprisingly, proved popular and was reissued in numerous editions and languages including Latin, French, Italian, and Czech. The last German edition was published in 1628, long after Münster's death of the plague in 1552. Cosmographia was one of the most successful and popular books of the 16th century, passing through 24 editions between 1544 and 1628. This success was due in part to its fascinating woodcuts (some by Hans Holbein the Younger, Urs Graf, Hans Rudolph Manuel Deutsch, and David Kandel). Münster's work was highly influential in reviving classical geography in 16th century Europe, and providing the intellectual foundations for the production of later compilations of cartographic work, such as Ortelius' Theatrum Orbis Terrarum Münster's output includes a small format 1536 map of Europe; the 1532 Grynaeus map of the world is also attributed to him. His non-geographical output includes Dictionarium trilingue in Latin, Greek, and Hebrew, and his 1537 Hebrew Gospel of Matthew. Most of Munster's work was published by his stepson, Heinrich Petri (Henricus Petrus), and his son Sebastian Henric Petri. More by this mapmaker...

Heinrich Petri (1508 - 1579) and his son Sebastian Henric Petri (1545 – 1627) were printers based in Basel, Switzerland. Heinrich was the son of the printer Adam Petri and Anna Selber. After Adam died in 1527, Anna married the humanist and geographer Sebastian Münster - one of Adam's collaborators. Sebastian contracted his stepson, Henricus Petri (Petrus), to print editions of his wildly popular Cosmographia. Later Petri, brought his son, Sebastian Henric Petri, into the family business. Their firm was known as the Officina Henricpetrina. In addition to the Cosmographia, they also published a number of other seminal works including the 1566 second edition of Nicolaus Copernicus's De Revolutionibus Orbium Coelestium and Georg Joachim Rheticus's Narratio. Learn More...

David Kandel (1520–1592) was a Renaissance artist, a pioneer of botanical and natural history illustration, and a prolific woodcut artist. His personal life is obscure. He is thought to have been born in Strasbourg, in 1520; He married in 1554 and 33 years later, in 1587, was recorded as "owner of a house". He died in 1592. His oeuvre was extremely broad, ranging from botanical illustrations to biblical events, largely as a product of his work as an illustrator. He produced about 550 of the superb woodcuts for Hieronymus Bock's 1546 Kreuterbuch (The Book of the Herbs). He produced many of the woodcuts appearing in Sebastian Münster's Cosmographia, including many of the maps and views, as well as his superb rendition of Dürer's sketch of a rhinoceros. Learn More...

Source

Munster's methodology in Cosmographia is notable in particular for his dedication to providing his readers with direct access to firsthand reports of his subjects wherever possible. Many of the maps were the result of his own surveys; others, the fruit of an indefatigable letter writing campaign to scholars, churchmen and princes throughout Europe, amicably badgering them for maps, views, and detailed descriptions of their lands. For lands further afield than his letters could reach, Munster relied on the best that the authorities of northern European scholarship could offer: he was well familiar with the work of Waldseemuller and other geographers of the early 16th century, and was well connected with the best geographers of his own generation. A disproportionate number of the maps of Cosmographia show contemporary geographical knowledge of the their respective areas for the very first time: The first map to show the continents of the Western Hemisphere; the first map to focus on the continent of Asia; the first modern map to name the Pacific Ocean; the first map to use a key; the first modern map of the British Isles and so on. Even in cases where earlier maps exist, Munster's works very often remain the earliest such acquirable by the collector.