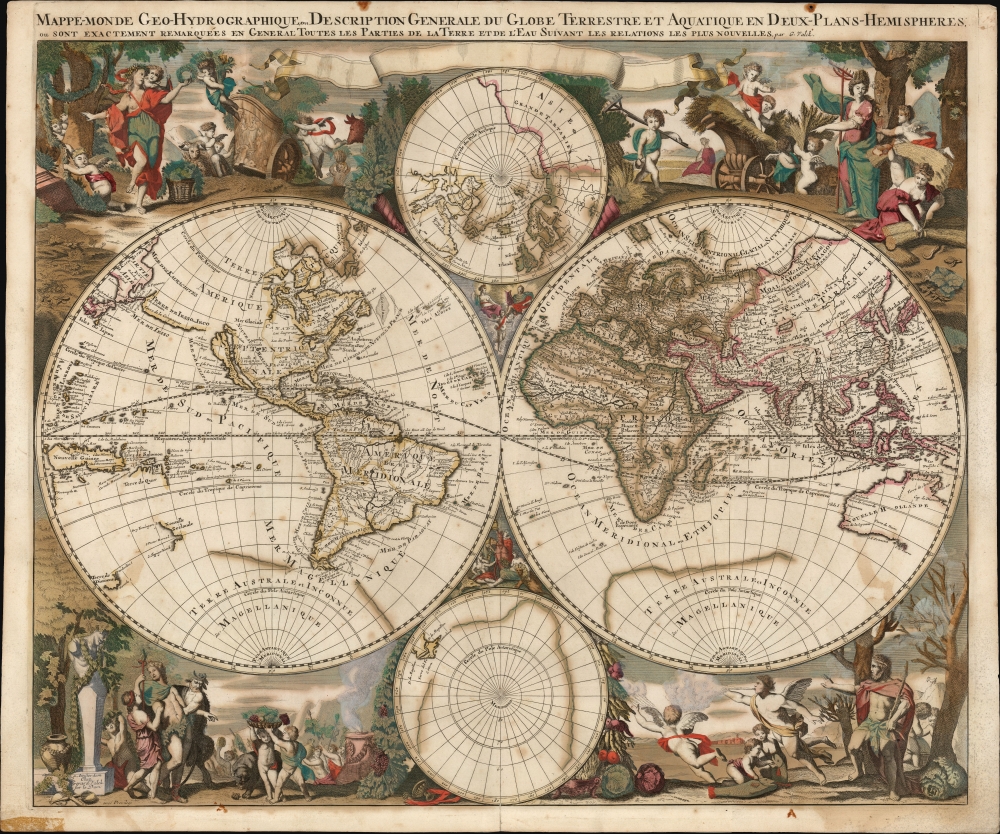

1686 Gerard Valck Map of the World

World-valk-1686

Title

1686 (undated) 19.5 x 22.75 in (49.53 x 57.785 cm) 1 : 90000000

Description

A Lively and Beautiful Engraving

Valk's work, aesthetically, fits squarely in the Dutch school of mapmaking with its artistry and decorative themes. The four vignettes depict the seasons and Zodiacal symbols. In a unique turn, each composition includes seasonal produce: Spring bursts with green garlands and flowers; Summer features grain in abundance; Autumn overflows with grapes; and Winter displays a wealth of root vegetables. The cusps of the hemispheres contain figures representing the continents: Asia, Africa, and America appear in the lower cusp; Europe is represented in the upper cusp by the classical elements of Venus, Cupid, and Apollo.A Closer Look

Valck's map geographically draws on the work of the French Nicolas Sanson as interpreted by Hubert Jaillot's cartography of 1674. The subordinate polar projections, for example, reflect the Dutch maps of Nicolas Visscher, but geographically reference Sanson.California as an Island

Although the notion first appears in print in the early 16th century, the first maps showing California as an island were published in England and the Netherlands in the 1620s. Sanson's wholehearted adoption of the myth in the middle of the 1600s entrenched the idea for the rest of the 17th century and well beyond Fr. Kino's 1710 debunking. By the time Valk's map was produced, insular California was geographical canon.New Mexico

East of the sea separating California from the mainland is Nouveau Mexique. Santa Fe is named on the banks of the Rio Norte, itself a conflation of the Rio Grande with the Colorado - the river is shown running from Santa Fe to the southwest rather than to the Gulf of Mexico. The river has its source in a gigantic (and imaginary) lake near lands associated with the Apache. This lake may result from reports of the Great Salt Lake from Onate and Coronado expeditions.Canada and The Great Lakes

The French geography of the northeastern portions of North America was more authoritative and accurate than that of contemporaneous Dutch mapmakers. Hudson's Bay appears in recognizable form, albeit with openings to the west, suggestive of hoped-for connections with the Pacific. Sanson's mapping of the Great Lakes was the first to show all five lakes, although lakes Superior and Michigan are shown with their western reaches left unfinished, again suggesting the possibility of a navigable water route to the Pacific. Labrador bears the placename Estotiland, the only holdover on this map of Nicolo Zeno's geographical fraud of the 16th century.Colonial America

Although the Northeast is dominated by 'Canada ou Nouvelle France,' the claims of France's European rivals are grudgingly acknowledged. Nouvelle Angleterre (New England), Nouveau Pays Bas (New Netherland / New York), and Nouvelle Suede (New Sweden / New Jersey) are shown - though squeezed down to the coastline, with the place names relegated to the ocean. Virginia is also named.The American Southeast

In Spanish Florida, which extends north to include most of the American Southeast, Lake Apalache or the 'Great Freshwater Lake of the American Southeast' is noted. This lake, first mapped by De Bry and Le Moyne in the mid-16th-century, is a mis-mapping of Florida's Lake George. While De Bry correctly mapped the lake as part of the River May or St. John's River, cartographers in Europe erroneously associated it with the Savannah River, which instead of flowing from the south to the Atlantic (Like the May), flowed almost directly from the Northwest. Lake Apalache was subsequently relocated somewhere in Carolina or Georgia, where it appears here.South America and El Dorado

The Caribbean is well understood and relatively detailed given the scale of the map. Southwards, despite the South American coastlands being well-mapped, the interior was largely unknown, giving rise to rampant speculation. Explorers throughout the late 16th and early 17th century, enthralled by Pizarro's conquests in Peru and tales of other gold-rich empires in the interior, were actively seeking El Dorado - which Sir Walter Raleigh placed in the mythical city of Manoa, which in turn was shown by Sanson on the shores of the Lake Parima, near modern-day Guyana.Further south, a large and prominent Laguna de Xarayes forms the northern terminus of the Paraguay River. Xarayes was often considered to be a gateway to the Amazon and the Kingdom of El Dorado.

Africa

The 17th-century mapping of Africa is similar to that of the New World, in that geographers were well informed of the coastline but for the most part ignorant of the interior. The present work follows the Ptolemaic two-lakes-at-the-base-of-the-Montes-de-Lune theory, as did every other mapmaker of this era. Just south of Sanson's Lake Zaire lies the Kingdom of Monomatapa. This region of Africa held a particular fascination for Europeans since the Portuguese first encountered it in the 16th-century. At the time, this was the empire of Mutapa or Monomotapa, which maintained a trading network with faraway partners in India and Asia.Asia

The mapping of Asia Minor, Persia, and India is fairly accurate. The Caspian Sea is corrected to a north-south axis, though its form is still poorly understood. Numerous Silk Route cities are named throughout Central Asia, including Samarkand, Tashkirgit, Bukhara, and Kashgar. Far to the north, he associates Tartaria, Mongolia, and Siberia with the Biblical lands of Gog and Magog - a common error related to European terror of the Mongol Invasions.The apocryphal Lake of Chiamay appears roughly in modern-day Assam, India. Early cartographers postulated that such a lake must exist to source the four important Southeast Asian river systems: the Irrawaddy, the Dharla, the Chao Phraya, and the Brahmaputra. This lake began to appear in maps of Asia as early as the 16th century and persisted well into the mid-18th-century.

Peninsular Korea, Speculative Northern Japan

Korea appears here correctly as a peninsula, though the narrow form derives from it having been rudimentary connection to the mainland - the peninsula otherwise resembles its insular depiction on earlier 17th century maps. Split between the two hemispheres of this map, the southern Japanese Islands are shown with some accuracy: for example, Edo or Tokyo Bay is recognizable, and several Japanese cities are noted. Hokkaido is shown attached to the continent. The Japanese Kuril Islands extend eastward to a massive Terre de la Compagnie, also named Terre de Jesso. Although these are names usually associated with Hokkaido, the land mass presented here is more commonly called Gama or Gamaland. Gama was supposedly discovered in the 17th century by a mysterious figure known as Jean de Gama. Several subsequent navigators claim to have seen this land, and it appeared on maps well into the late 18th century. At times it was associated with Hokkaido in Japan, and at other times with fictitious islands, and occasionally with the mainland of North America.Early South Pacific Discoveries

Australia, New Zealand, and the South Pacific were virtually unknown to European explorers. The depiction of these lands on all maps from the middle of the 17th century until Cook's voyages is based on the 1642 mapping of Abel Tazman. For over a century, only a portion of the west coasts of Australia and New Zealand, and the southern reaches of Tasmania, were to appear on maps. A mysterious 'Terre de Quir' is shown as well: a great landmass supposedly discovered by the 16th-century Spanish navigator and religious zealot Pedro Fernandez de Quiros (1565 - 1615). Quiros set sail in search of the speculative Terre Australis and likely discovered several important South Seas islands. Nonetheless, Quiros turned back just shy of glory shortly before sighting New Zealand. Even so, Quiros was a voracious self-promoter, and descriptions of his findings were circulated throughout Europe. Terre de Quir or Terre de Quiros appears on various maps of the region until put to rest by the 18th-century explorations of Captain Cook.Terre Australe Incognita

On most 16th-century maps, the Southern Hemisphere was dominated by a great continent typically named 'Terre Australe Incognita,' or some variation. Despite the tenacity of geographical authorities on the matter, cartographers of the 17th and 18th centuries would gradually whittle away the coastline as one expedition after another failed to discover it. The depiction of Antarctica here, dating from the 1660s, shows the coastline pared away from 'Nouvelle Holland' and Magellanica. By the end of the century, most maps dispensed with 'Terre Australe' entirely as geographers came to admit the extent to it was 'incognita'. Antarctica itself was not truly discovered until Edward Bransfield and William Smith sighted the Antarctic Peninsula in 1820.Publication History and Census

Shirley dates the map to 1686, based on the inclusion of Valk's privilege (obtained that year.) Earlier imprints were available as separate issues or included in composite atlases. The map does appear, without change, in editions of Valk's atlas Nova Totius Geographica Telluris Projectio as late as 1711. The map, sometimes dated arbitrarily, is well-represented in institutional collections and appears on the market from time to time.CartographerS

Gerard Valk (September 30, 1652 - October 21, 1726) (aka. Valck, Walck, Valcke), was a Dutch engraver, globe maker, and map publisher active in Amsterdam in the latter half of the 17th century and early 18th century. Valk was born in Amsterdam where his father, Leendert Gerritsz, was a silversmith. He studied mathematics, navigation, and cartography under Pieter Maasz Smit. Valk and moved to London in 1673, where he studied engraving under Abraham Blooteling (or Bloteling) (1634 - 1690), whose sister he married, and later worked for the map sellers Christopher Browne and David Loggan. Valke and Blooteling returned to Amsterdam in 1680 and applied for a 15-year privilege, a kind of early copyright, from the States General, which was granted in 1684. In 1687, he established his own firm in Amsterdam in partnership with Petrus (Pieter) Schenk, who had just married his sister, Agata. They published under the imprint of Valk and Schenk. Also, curiously in the same year Valk acquired the home of Jochem Bormeester, also engraver and son-in-law of art dealer Clement De Jonghe. Initially Valk and Schenk focused on maps and atlases, acquiring the map plates of Jodocus Hondius and Jan Jansson in 1694. Later, in 1701 they moved into the former Hendrick Hondius (the younger) offices where they began producing globes. Valk and Schenk soon acquired the reputation of producing the finest globes in the Netherlands, a business on which they held a near monopoly for nearly 50 years. In 1702, Valk joined the Bookseller's Guild of which he was promptly elected head. Around the same time, Gerard introduced his son, Leonard, who was married to Maria Schenk, to the business. Leonard spearheaded the acquisition of the map plates of Frederick de Wit in 1709. Nonetheless, Leonard was nowhere near as sophisticated a cartographer or businessman as his father and ultimately, through neglect, lost much the firm's prestige. After his death, the firm was taken over by his widow Maria. More by this mapmaker...

Nicolas Sanson (December 20, 1600 - July 7, 1667) and his descendants were the most influential French cartographers of the 17th century and laid the groundwork for the Golden Age of French Cartography. Sanson was born in Picardy, but his family was of Scottish Descent. He studied with the Jesuit Fathers at Amiens. Sanson started his career as a historian where, it is said, he turned to cartography as a way to illustrate his historical studies. In the course of his research some of his fine maps came to the attention of King Louis XIII who, admiring the quality of his work, appointed Sanson Geographe Ordinaire du Roi. Sanson's duties in this coveted position included advising the king on matters of geography and compiling the royal cartographic archive. In 1644, he partnered with Pierre Mariette, an established print dealer and engraver, whose business savvy and ready capital enabled Sanson to publish an enormous quantity of maps. Sanson's corpus of some three hundred maps initiated the golden age of French mapmaking and he is considered the 'Father of French Cartography.' His work is distinguished as being the first of the 'Positivist Cartographers,' a primarily French school of cartography that valued scientific observation over historical cartographic conventions. The practice result of the is less embellishment of geographical imagery, as was common in the Dutch Golden Age maps of the 16th century, in favor of conventionalized cartographic representational modes. Sanson is most admired for his construction of the magnificent atlas Cartes Generales de Toutes les Parties du Monde. Sanson's maps of North America, Amerique Septentrionale (1650), Le Nouveau Mexique et La Floride (1656), and La Canada ou Nouvelle France (1656) are exceptionally notable for their important contributions to the cartographic perceptions of the New World. Both maps utilize the discoveries of important French missionaries and are among the first published maps to show the Great Lakes in recognizable form. Sanson was also an active proponent of the insular California theory, wherein it was speculated that California was an island rather than a peninsula. After his death, Sanson's maps were frequently republished, without updates, by his sons, Guillaume (1633 - 1703) and Adrien Sanson (1639 - 1718). Even so, Sanson's true cartographic legacy as a 'positivist geographer' was carried on by others, including Alexis-Hubert Jaillot, Guillaume De L'Isle, Gilles Robert de Vaugondy, and Pierre Duval. Learn More...

Alexis-Hubert Jaillot (c. 1632 - 1712) followed Nicholas Sanson (1600 - 1667) and his descendants in ushering in the great age of French Cartography in the late 17th and 18th century. The publishing center of the cartographic world gradually transitioned from Amsterdam to Paris following the disastrous inferno that destroyed the preeminent Blaeu firm in 1672. Hubert Jaillot was born in Franche-Comte and trained as a sculptor. When he married the daughter of the Enlumineur de la Reine, Nicholas I Berey (1610 - 1665), he found himself positioned to inherit a lucrative map and print publishing firm. When Nicholas Sanson, the premier French cartographer of the day, died, Jaillot negotiated with his heirs, particularly Guillaume Sanson (1633 - 1703), to republish much of Sanson's work. Though not a cartographer himself, Jaillot's access to the Sanson plates enabled him to publish numerous maps and atlases with only slight modifications and updates to the plates. As a sculptor and an artist, Jaillot's maps were particularly admired for their elaborate and meaningful allegorical cartouches and other decorative elements. Jaillot used his allegorical cartouche work to extol the virtues of the Sun King Louis IV, and his military and political triumphs. These earned him the patronage of the French crown who used his maps in the tutoring of the young Dauphin. In 1686, he was awarded the title of Geographe du Roi, bearing with it significant prestige and the yearly stipend of 600 Livres. Jaillot was one of the last French map makers to acquire this title. Louis XV, after taking the throne, replaced the position with the more prestigious and singular title of Premier Geographe du Roi. Jaillot died in Paris in 1712. His most important work was his 1693 Le Neptune Francois. Jalliot was succeeded by his son, Bernard-Jean-Hyacinthe Jaillot (1673 - 1739), grandson, Bernard-Antoine Jaillot (???? – 1749), and the latter's brother-in-law, Jean Baptiste-Michel Renou de Chauvigné-Jaillot (1710 - 1780). Learn More...