This item has been sold, but you can get on the Waitlist to be notified if another example becomes available, or purchase a digital scan.

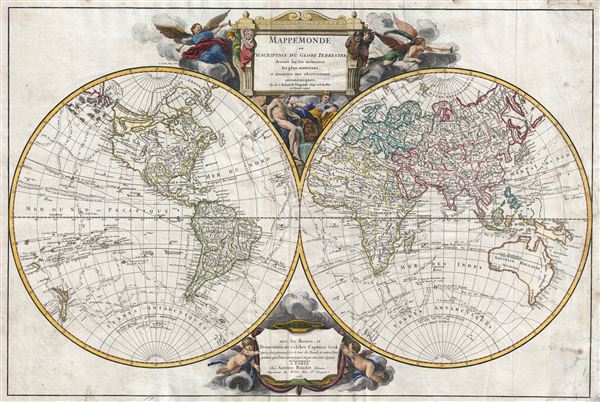

1783 Vaugondy Map of the World in Hemispheres

World-vaugondy-1783

Title

1783 (dated) 19 x 28 in (48.26 x 71.12 cm) 1 : 70000000

Description

This map occupies a very ephemeral period between the completion of Cook's Third Voyage in 1780 and the publication of his journals and maps in 1784. Cartographers were vaguely aware of his discoveries and some new cartographic information had leaked, but few had any real idea of the extent of his explorations. The discoveries of Cook redefined the map of the world on many levels from finally disproving the speculative Terre Australis, to firmly and accurately mapping the coasts of Australia, New Zealand, and Polynesia, and most significantly, to leading the first scientific expedition to North America's Pacific Northwest. On many levels Cook's explorations made most previous maps of the world obsolete. This was a hard blow to many 18th century cartographers whose business model relied on republication of older material. Despite being a grand scientific enterprise, the cartographic conventions established in the previous century proved tenacious even in the light of Cook's discoveries.

Such is readily apparent in this maps' presentation of North America. The map attempts to combine the speculative cartography of De Fonte, de Fuca, with highly questionably early 18th century reports by the likes of Lahonton and the Count of Penalosa. Focusing fist on the odd network of lakes, inland seas, and rivers lying between the Hudson Bay and the Straits of Anian, we can see a legacy representation of the apocryphal De Fonte Discoveries.

The De Fonte legend first appeared in a 1706 English publication entitled Memoirs of the Curious. This short-lived magazine published a previously unknown account by a supposed Spanish Admiral named Bartholomew de Fonte. De Fonte is said to have sailed up the Pacific coast of North America in 1640. On this voyage he apparently discovered a series of gigantic lakes, bays, and rivers heading eastward from the Pacific towards Hudson Bay. The De Fonte story relates how, on one of these great inland lakes, he met with a westward bound ship from Boston that must have come through the Northwest Passage. Today, based upon inaccuracies and falsities, we know the entire De Fonte article to have been a fabrication, and nevertheless, it set 18th century Europe afire with speculation that a Northwest Passage must indeed exist. Even such luminaries as Benjamin Franklin wrote long defenses of De Fonte.

Vaugondy has here placed the entrances to De Fonte's lake and river system in Cook's Inlet near today's Anchorage, much further north than most previous maps. Cook's Inlet was not fully explored by the final Cook expedition and was thus presumed to be the only possible entrance to the Northwest Passage. Here Vaugondy has associated both Cook's Inlet and Prince William Sound with the De Fonte Discoveries. We can recognize the Lac de Fuentes as well as Lac Belle, and the Rio de los Reyes. Many of the water communications here are conjectural but would later be echoed by Buache de Neuville, a bitter enemy of the Vaugondys. Lac de Fonte seems to roughly correspond with Great Slave Lake. The factual Mackenzie River is nowhere in evidence, but a second fictional river extending westward towards Prince William Sound and Cook's Inlet, also copied by Buache in a later map, may well have its first expression here.

Another legacy of the De Fonte voyage appears further north in the form of passages extending northwards from Cook Inlet towards Lac Velasco, thence via a river communication to the high Arctic, as well as another ship's route passing through the Bering Strait and then heading eastwards toward Baffin Bay. This refers to the travels of Pedro de Bernarda, a sub-Captain under Admiral De Fonte. According to the legend, on the 22nd of June, De Fonte dispatched Bernarda northwards where he discovered a large lake full of islands, which he named 'Velasco' after the Governor of New Spain. He then traveled through the Bering Strait and sailed eastward almost as far as Baffin Bay. The travels of Bernarda are marked here skirting the coasts of Alaska and the Canadian Arctic. There is also a river named after him called the Rio de Bernarda. Like De Fonte, Bernarda was most likely fictional but his explorations were nonetheless used by Captain James Ross in his 1835 argument for a possible Northwest Passage.

Another interesting river system extends inland from the Strait of Juan de Fuca becoming the 'Riviere de L'Ouest' (naturally assumed by most to be some sort of proto-representation of the as yet undiscovered Columbia River) before meeting up with Lake Tahuglaucks and thus the conjectural discoveries of Lahonton. Unlike De Fonte, many of De Fuca's discoveries, as well as the man himself, ring of truth. The Strait of Juan de Fuca exists and, though it was named much later, roughly corresponds to De Fuca's actual descriptions. Cook notes sailing past the entrance described by De Fuca but did not explore the strait further. Had he done so he would have found himself in the Puget Sound region later explored by George Vancouver and Amiel Weeks Wilkes. Instead, as with Cook's Inlet, Vaugondy capitalizes on another of Cook's omissions by speculatively linking the Strait of Juan de Fuca with Lahonton's discoveries.

Baron Louis Armand de Lahonton (1666-1715) was a French military officer commanding the fort of St. Joseph, near modern day Port Huron, Michigan. Abandoning his post to live and travel with local Chippewa tribes, Lahonton claims to have explored much of the Upper Mississippi Valley and even discovered a heretofore unknown river, which he dubbed the Longue River, here presented running westward of the Mississippi from a point south of the Missouri. This river he claims to have followed a good distance from its convergence with the Mississippi. Beyond the point where he himself traveled, Lahonton wrote of further lands along the river described by his American Indian guides. These include a great saline lake or sea at the base of a mountain range. This range, he reported, could be easily crossed, from which further rivers would lead to the mysterious lands of the Mozeemleck and Tahuglaucks, and presumably the Pacific. LahontonÂ's work has been both dismissed as fancy and defended speculation by various scholars. Could Lahonton have been describing indigenous reports of the Great Salt Lake? Could this be a description of the Missouri and Columbia Rivers? What river was he actually on? Perhaps we will never know. What we do know is that on his return to Europe, Lahonton published an enormously popular book describing his travels. LahontonÂ's book inspired many important cartographers of his day, Sennex, Vaugondy, Moll, Delisle, Popple, Sanson, and Chatelain to name just a few, to include on their maps both the Longue River and the saline sea beyond. The concept of an inland river passage to the Pacific fired the imagination of the French and English, who were aggressively searching for just such a route. Unlike the Spanish, with easy access to the Pacific through the narrow isthmus of Mexico and the port of Acapulco, the French and English had no easy route by which to offer their furs and other commodities to the affluent markets of Asia. A passage such as Lahonton suggested was just what was needed and wishful thinking more than any factual exploration fuelled the inclusion of LahontonÂ's speculations on so many maps.

Otherwise this presentation of North America follows conventions established in France during previous decade of speculative mapping. The western part of the continent bulges out to accomidate the mythical kingdoms of Teguayo, Quivara, and Anian. The Missouri connects with an embryonic representation of Lake Winnepeg. The Aleutians are speculative and unrecognizably placed in accordance with limited Russian explorations in this region.

Leaving North America our examination of this map moves on to South America. Exhibiting considerable updates over Vaugondy's 1752 world map, South America as presented here lacks many of the speculative geographic elements common to earlier maps of the regions, such as el Dorado and Lake Parima. The Lago de Xarayes does remain. The Xarayes, a corruption of 'Xaraies' meaning 'Masters of the River', were an indigenous people occupying what are today parts of Brazil's Matte Grosso and the Pantanal. When Spanish and Portuguese explorers first navigated up the Paraguay River, as always in search of el Dorado, they encountered the vast Pantanal flood plain at the height of its annual inundation. Understandably misinterpreting the flood plain as a gigantic inland sea, they named it after the local inhabitants, the Xaraies. The Laguna de los Xarayes almost immediately began to appear on early maps of the region and, at the same time, took on a legendary aspect as the gateway to the Amazon and the kingdom of el Dorado.

South of the equator the shores of Australia or New Holland are well maps for the first time, reflecting Cook's work, though Van Diemen's Land or Tasmania remains attached to the mainland. New Guiniea, a little further north, is mapped speculatively with its southern shoreline ghosted in - suggestive of unknown lands.

By contrast the northeast parts of Asia, which had recently been explored by Vitus Bering and Tschirikow, are depicted with a fair approximation of accuracy. Terre de Gama and Terre de la Company, speculative mis-mappings of the Japanese Kuril Islands by the 17th century Dutch explorers Maerten de Vries and Cornelis Jansz Coen , appear just northeast of Yedso (Hokkaido). Gama or Compagnie remained on maps for about 50 years following Bering's voyages until the explorations of Cook confirmed the Bering findings. North of Japan and west of Kamtschatka Vaugondy has mapped the 'Sea of Love'.

Polynesia is mapped with numerous islands named, but few are the correct size or in the correct place. Hawaii, which had just been discovered by Cook, here makes its first appearance in a Vaugondy map. What is shown is 'Terre de Davis' roughly where Easter Island is today. Terre de Davis or Davis' Land was supposedly discovered in 1688 by an English navigator of the same name. Many historians argue whether or not Davis Land was actually Easter Island, but it does seem likely.

This map's dramatic title cartouche deserves special attention. The cartouche was designed by artist Charles Nicolas Cochin and it one of the 18th century cartouche designs for which the original drawing remains, in this case in the holdings of the British Museum. The Vaugondys must have been impressed with the cartouche but unsatisfied with its orientation, for they commissioned Pierre F. Tardieu to engrave it, the orientation was reversed. The cartouche, which includes both decorative and allegorical elements ranging from angels and putti to Adam and Eve, is signed both by Cochin and Groux. Little is known of Charles-Jacques Groux. He was the son in law of the painter J. B. Noel and his name appears on many later editions of Vaugondy's maps, particularly as a signatory on the cartouches work, which though neither updated nor his own work, he nonetheless claimed.

This map was first prepared in 1752 by the Robert de Vaugondy firm. The map went through four subsequent states, in 1742, 1768, 1776, and 1783. The present example is the fourth and final state. All examples were prepared for the Atlas Universel, which was published jointly by the Robert de Vaugondy's and Chez Antoine Boudet. Most of the maps prepared for Atlas Universel were also sold separately.

Cartographer

Robert de Vaugondy (fl. c. 1716 - 1786) was French may publishing from run by brothers Gilles (1688 - 1766) and Didier (c. 1723 - 1786) Robert de Vaugondy. They were map publishers, engravers, and cartographers active in Paris during the mid-18th century. The father and son team were the inheritors to the important Nicolas Sanson (1600 - 1667) cartographic firm whose stock supplied much of their initial material. Graduating from Sanson's maps, Gilles, and more particularly Didier, began to produce their own substantial corpus. The Vaugondys were well-respected for the detail and accuracy of their maps, for which they capitalized on the resources of 18th-century Paris to compile the most accurate and fantasy-free maps possible. The Vaugondys compiled each map based on their own geographic knowledge, scholarly research, journals of contemporary explorers and missionaries, and direct astronomical observation. Moreover, unlike many cartographers of this period, they took pains to reference their sources. Nevertheless, even in 18th-century Paris, geographical knowledge was limited - especially regarding those unexplored portions of the world, including the poles, the Pacific Northwest of America, and the interiors of Africa, Australia, and South America. In these areas, the Vaugondys, like their rivals De L'Isle and Buache, must be considered speculative or positivist geographers. Speculative geography was a genre of mapmaking that evolved in Europe, particularly Paris, in the middle to late 18th century. Cartographers in this genre would fill in unknown lands with theories based on their knowledge of cartography, personal geographical theories, and often dubious primary source material gathered by explorers. This approach, which attempted to use the known to validate the unknown, naturally engendered rivalries. Vaugondy's feuds with other cartographers, most specifically Phillipe Buache, resulted in numerous conflicting papers presented before the Academie des Sciences, of which both were members. The era of speculative cartography effectively ended with the late 18th-century explorations of Captain Cook, Jean Francois de Galaup de La Perouse, and George Vancouver. After Didier died, his maps were acquired by Jean-Baptiste Fortin, who in 1787 sold them to Charles-François Delamarche (1740 - 1817). While Delamarche prospered from the Vaugondy maps, he defrauded Vaugondy's window Marie Louise Rosalie Dangy of her rightful inheritance and may even have killed her. More by this mapmaker...